If you’re on social media, you’ve likely read a list, by someone much wealthier and/or better connected than you (power to them), listing the best golf courses that they played during the past year. It’s obnoxious (again, power to them). What makes it worse is when their summaries are less insightful-look-into-the-minutiae-of-golf-course-identity, and more I-was-there photo dumps.

I’m a cynic. I don’t believe the perfect golf course exists, in the same way that I don’t believe many truly terrible golf courses exist. I, a blogger and social media guy, provide very little value to you if I don’t emphasize fatty spots on what is otherwise a fine cut of meat. And that’s how I came up with my annual “best of” format: Rather than simply slobbering to you about how great a course like Bandon Dunes is, I choose my least favorite hole and offer suggestions for improvement.

That would be too easy, however, so there’s a twist:

Each hole is redesigned from the mindset of a different golf course architect. A golf course architect from elsewhere on my year-end list, whose own hole will be dissected in the style of one of his cohorts later on. Confused? You’ll figure it out. Let’s start with a tough one, and hopefully learn something about these architects and some otherwise pretty great courses.

So…what would happen if HERBERT FOWLER renovated NO. 6 at BANDON DUNES?

What would happen if HERBERT FOWLER renovated NO. 6 at BANDON DUNES?

I’m starting out with the toughest one first, for two reasons. One, to get it out of the way and two, because I’m going in alphabetical order. Bandon Dunes is the only course I played this year that appears on the world top 100 for all three publications I refer to for such things. That said, there’s plenty of room for improvement. The Fried Egg did a great rundown of these issues in an eye-opening podcast, which made me reconsider many things. One of the glaring problems they didn’t need to tell me about, however, was obvious as soon as I walked off its green.

No. 6 is the second par three at Bandon Dunes and, in a vacuum, it’s a pretty good hole. It’s tough to slap a par three along the coast like that and fail. Minus the vacuum, considering there are 17 other holes, and suddenly there’s an issue. Its tees and No. 7’s tees are neighbors, almost equidistant to the green. No. 6 is a routing nightmare befitting a mid-tier residential course: the par three where you tee off, walk to the green, and walk back to where you started for the next tee.

How to fix it? Let’s start with the obvious: The green needs to be on the cliff, right?

I’d argue “no.”

The appeal of cliffside golf is understandable, but also overrated. Think of how many of the great linksland courses actually play right along the ocean. Not too many. I’d argue the “retail golfer,” to use Mike Keiser’s words, is just as happy to see the ocean from a cliff as incorporating it strategically into a hole. But I’m writing this post for GCA nerds, so let’s ignore our baser instincts and think about how we can create a pretty solid hole that ends much nearer to the No. 7 tees.

Important note: I don’t know how feasible this hole is, from an ecological perspective. In an ideal world, the rest of the routing would flex in some way so that David McLay-Kidd could weasel in a short hole somewhere else. But this exercise only gives me the right to alter one hole, so here’s what me and Herbert Fowler came up with.

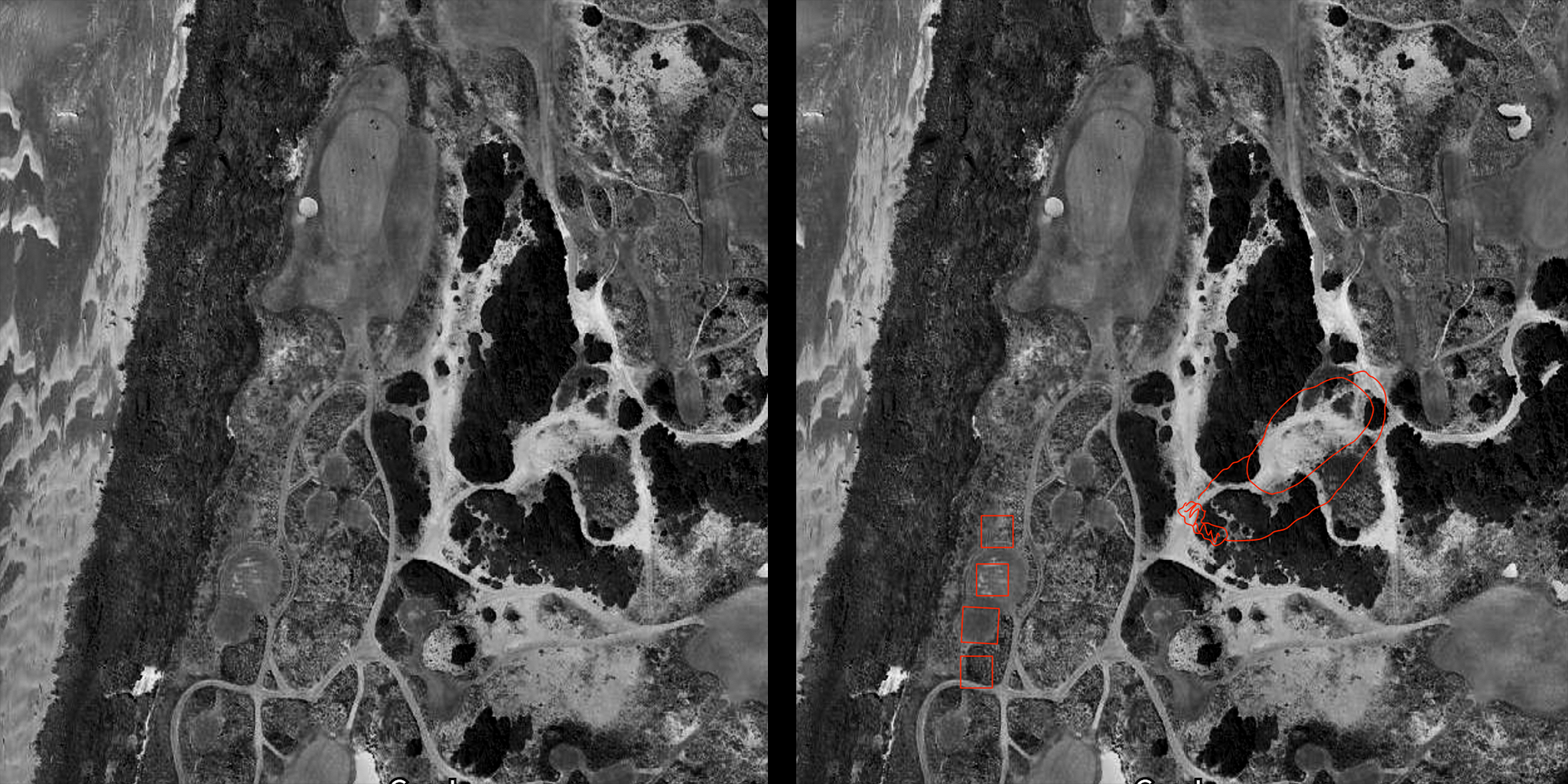

Skwisgaar Skwigelf might say that it looks cool, but it does not routes for us very well. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Skwisgaar Skwigelf might say that it looks cool, but it does not routes for us very well. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Fowler — from my limited understanding — looked for green sites first, emphasizing natural locations, and then made the rest of the hole work toward this point. Based on the 36 Fowler holes I played at The Berkshire this year, he had a knack for par threes, which makes me wonder if he focused on these holes first, much like Stanley Thompson.

I’m not going to pretend the sandy area just north of the No. 7 tees is the most “natural” in a Sand Hills sense. It may currently provide extra sand for around the course. But, I reckon that by clearing back what-I-assume-to-be gorse (for which nature lovers in south Oregon are actually pro-removal), we can plant a green similarly sized to what currently exists.

This does trim a significant distance from the current hole length, down to about 151 yards from the back tee (which I’ve added to the current mid-length tee). This, however, accounts for an element of blindness that’s been added. The foremost area visible from the back tee will be an added bunker, well ahead of the green. There will be short grass added around the putting surface from noon to 6:30, with more room to miss to the right (this area becomes more visible as you move up to shorter tee boxes). The safe area short of the green is longer than it appears from the tee.

Is it as glamorous as the hole it’s replacing? I reckon not. Does it put you 100 yards closer to No. 7’s tee when you come off the green? Very much so.

Inland and onward, with a much shorter walk to the No. 7 tee. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Inland and onward, with a much shorter walk to the No. 7 tee. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

What would happen if COORE & CRENSHAW renovated NO. 1 at THE BERKSHIRE (RED)?

Before Fowler starts feeling all high-and-mighty, let’s take a knife to one of his babies. The Berkshire’s Red Course was, prior to Cabot Cliffs, the world’s most well-known 6-6-6 routing, featuring six par threes, six par fours, and six par fives. It’s an interesting concept, to be sure, and Red is well-routed so that none of the par types crowd into each other. The par threes are magnificent. But there’s one problem with par fives: They take up a lot of space.

From a strokeplay perspective, the six par fives struggle for lack of length. Or, at least, a lack of variety in that they’re all reachable in two shots, given the proper weather conditions. This includes the opening hole, which plays plays just 510 yards from the back tee. There’s a drainage stream that crosses the fairway, but I imagine in proper heathland conditions (plenty of bounce), getting across this thin channel from 265 yards out is possible. Even if you lay up, it’s less than 200 yards to the green from the stream. Fowler is noted, generally, for his sparing use of fairway bunkering. Reasonable enough…but zero traps across this short par five sets up an opener that’s less than a gentle handshake. It’s a rather flaccid one.

The good news is that among my collection of architects this year, there’s a duo that’s previously worked on a prominent, sand-based site with few actual bunkers. Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw and, of course, Pinehurst No. 2.

There’s plenty of worthy comparisons to be made between the signature courses of the Carolina sand hills and the London heath. One, the sand. Two, architects tended to provide wide fairways with no actual rough, in the grass sense. If you manage to miss the short stuff (which is quite possible when the turf is bouncing at its peak pace), you’ll find native hazard. At Pinehurst, it’s waste and scrub. West of London, it’s acres of heather, a native ground cover that blooms beautiful purple, but more importantly creates unpredictable lies. Your ball could sit up, get wedged in, or somewhere in between. The safe bet is just to stay out.

That’s why Coore and Crenshaw are comfortable burying the stream; it’s a hazard, but an awkward one. Instead, we’ll emphasize the heather that begins about 296 yards from the back tees and pinches the fairway from the left for about 30 yards.

This doesn’t mean expanding it — it’s large enough as is. It means exaggerating the importance, upon approach, of leaving one’s tee shot near this mess. There will be two options for those who want to try getting home in two: One, the safer option, is to play to the front of the heather. This will give them the best line in, but also require at least 215 yards to get to the green. The second option is for the tigers to knit their tee shot along the left side of the heath or, even better, hit a monstrous draw that ends up about 322 yards out. With the stream covered and the Summer turf bouncing, it’s not impossible.

Bill and Ben will turn to the Pinehurst playbook to ensure the approach still tests the mettle after a strong tee shot. Adding two bunkers that jut out from the left, perhaps 30 and 50 yards out, may daunt some into a poor shot. If not, the green should be redesigned to more aggressively rebuff approaches from the right. Perhaps not quite a Pinehurst saucer, but something angled front-and-left.

Those who took the conservative route from the tee will be wise to lay up ahead of the fairway bunkers in order to get home in three; the nearer of the two sand hazards sticks farther into the fairway to discourage these golfers from cutting a diagonal toward the front of the green. Those who try to carry the full distance from the right run the risk of rolling into the collection area to the right, creating a tough pitch up to a green that runs away.

The hole still allows eagle opportunities, but has increased the opportunities for strategic split-paths. Ironically, Coore and Crenshaw used Rossian thought to develop their update — Donald was noted for (somewhat unfairly) hating Fowler’s guts.

Still not quite as stiff as the Blue Course’s opener, but a bit more muscle nonetheless. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Still not quite as stiff as the Blue Course’s opener, but a bit more muscle nonetheless. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

What would happen if DAVID MCLAY-KIDD renovated NO. 5 at HYDE PARK COUNTRY CLUB?

Donald Ross is renowned as one of the best routers in golf course design’s long history. He’s known a bit less widely for being among the better PR folks in the industry as well; there’s a reason why he wasn’t among the MacKenzies and Tillinghasts, who died penniless. One, he drank less, but two, he was always on the right side of the message. It would be a no-brainer for him to blame No. 5 at Hyde Park Country Club on Tom Bendelow, the Johnny Appleseed of American golf course, and who also gave Ross ripe pickings for a renovation tour of Ohio.

Hyde Park, however, was a full redesign. We’ll acknowledge that there’s a chance No. 5 only got worse during a later Dick Wilson renovation — it at least got 40 yards longer — but the underlying truth throughout is that the hole sits on the worst part of the property. Take a peek at Hyde Park on a Google topographic map and it looks like a ripped Patrick Star. No. 5 runs along the left side of his head, a non-muscular area, all the way to the tip.

Sure, it begins with some star potential, a lofty tee shot down from the crest where the No. 4 green sits…and then it’s just flat fairway and a few unattractive bunkers for the rest of this par five. For further context, the next hole hole is a much better par five, opening the door for unflattering comparisons.

Looking back at what could be from the No. 5 green. (Photo Cred: Jason Liebert)

Looking back at what could be from the No. 5 green. (Photo Cred: Jason Liebert)

Enter David McLay-Kidd. He’s not a template guy per se, but he knows that good reviews must mean something. Hence his decision to recreate a mirror version of Gamble Sands No. 2 here at Hyde Park.

This is a rather dramatic overhaul, bringing No. 5 from a gettable par five to a drivable par four. At Sands, a big hitter can try to thread the gap between a sizable trench and the left edge of the fairway, potentially riding down to the green. The rest of us will play out to the right, avoiding the trench and angling a short approach back to the left.

First, due to the area on the property, we’re going to flip the hole so players now need a power fade instead of a power draw to hunt for this green. Kidd will remove the existing fairway bunkers, as well as trim some trees, so that he can expand the fairway dramatically to the left, for a more conservative audience. Just as important is trimming the trees to the immediate left of the teebox; per a discussion with a Hyde Park member, the property expands far enough to get some of them out of there. This will open up an angle for the conservative player to aim out left.

The tee shot at Gamble Sands is downhill, but not nearly as aggressively as this one. Still, we can probably leave the distance about the same. Hyde Park is the only course in Ohio that touts Zoysia fairways, which provides a bit more stick than other turfs. Few shots will reach this green from the tee by lucky bounce alone.

Although a few dummies (including you and I) will take aim at the green, the question asked to the average player will be how far left to travel from the centerline bunker; any shot in that direction will provide a satisfactory angle into the green, but a shorter shot awaits those who attempt to clip that corner of the bunker.

What this hole lacks compared to its Gamble Sands forbearer is terrain that will move balls toward the green once they cross the hazard. You can’t always get what you want but perhaps, on the most boring segment of an otherwise exciting property, we can at least get what we need.

Looking back at what could be from the No. 5 green. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Looking back at what could be from the No. 5 green. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

What would happen if DONALD ROSS renovated NO. 15 at MAYFIELD COUNTRY CLUB?

Mayfield Country Club tends to split players; half are fans of its “quirk” while the other half find it annoying. This “quirk” can largely be described as “blind tee shots,” where the designers had little choice but to place an aiming stick at the crest of this property’s high, rolling hills, so that players could take aim and hit it high. This starts off well enough; nos. 2 and 9 (especially the latter) are charming. No. 11, a par five, has an essence of Perranporth in that you’ll possibly have multiple blind shots on your way to the green. The odd flow probably didn’t bother primary designer Bert Way too much; he began his golf career as the pro at Royal North Devon, a proudly offbeat English club.

But by No. 15, you’ve had enough. Well, maybe not, but typically one saves the best for last. No. 15 is not the best. It’s a long tee shot up a steep hill, where the fairway suddenly flattens out and remains so for the next 210 yards into the green. On a course where there are several excellent blind tee shots, it seems lame to end with the worst of them.

Donald Ross, and a better read on the property’s terrain, can help. It’s appropriate that the Scot helps us out here; some mistakenly believe Mayfield was one of his designs, a rumor that probably originated in his work at the since-shuttered Acacia Golf Course next door.

First, let’s look at how the terrain can help a seasoned router like Ross make a better hole here. Take a look at a topographical map, and you’ll see that, underneath the trees, an even-steeper hill (similar in height and angle to the tee shot from No. 17) sits along the right, almost a perfect “Cape” setup. Clear out a few rows of trees, and a natural hazard emerges. The only natural thing to do, unless you’re Rees Jones at Torrey Pines, is to expand the fairway to ride the edge of the hill, and move the green over to lie flush.

There are many architects noted for this style of hole, however, so let’s make it a bit more Ross by utilizing his “switchback” philosophy, or calling for two-different shot shapes in order to get the best birdie putt. We only need two bunkers to enforce this idea.

The first is a big one: a large sand area built into the side of the upward hill, to the left side of the fairway. This will be Der Keiser in scope (see the largest bunker on the closing hole at Pacific Dunes), absolutely intended to intimidate. A full carry from the back tee is only 160 yards, which is entirely doable even with the steep uphill. The penalty for coming up short, however, may shake some from attempting the carry. Skilled players can use a draw to start right and wrap back around the hazard. This landing area will provide the best angle in.

A note: Yes, this ultimately encourages conservative golfers to play toward the “cliff” hazard from the tee. The cape shape of that drop-off means there is more landing area at the front of this fairway than nearer to the green. If you’re among the many who assume that a play toward the edge should result in a better angle, I encourage you to look again at Macdonald’s own “Cape” hole. In this case, it’s shots away from the hazard that provide a better angle in, but from a longer distance. Those who attack Macdonald’s hazard from the tee get a shorter approach distance, but no angular benefit. This dichotomy would have been less pronounced in Ross’s version at Mayfield, hence why we added the scary monster bunker to the left.

The second bunker is less dramatic, but just as effective for enforcing the switchback. Located at the front left of the green (which we expanded in size), this allows those who made the requisite draw from the tee to play a slight fade without worrying about the green’s singular sand hazard. Those who played to the safe area off the tee can still reach the green, but it will require a much more pronounced fade, flirting with the edge of the rightward “cliff” all the way. If they start the ball on the correct line but fail to fade enough, they could drop right into this second bunker.

Quirk preserved, strategic interest enhanced.

Hills ‘n’ thrills at the Mayfield No. 15. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

Hills ‘n’ thrills at the Mayfield No. 15. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graphics Team)

What would happen if SETH RAYNOR renovated NO. 17 at BANDON’S SHEEP RANCH?

Was the edit we made above at Mayfield Country Club not as exciting as you would have hoped? Cleared a few trees…open up a steep embankment…not enough to get the blood flowing for you? Alright. Let’s look at a hole with an actual cliff: No. 17 at Bandon’s Sheep Ranch.

It’s tough to go wrong with such a long stretch of cliffside but the penultimate hole leaves something to be desired. Much of this comes down to relativity. No. 17 is sandwiched between the most visually impressive par three on the course — maybe even the property — and a par five that probably allows more eagles than any hole at Bandon. Then you can compare it against the other par fours at Bandon that offer oceanic views from tee to green: Bandon Dunes No. 16, Pacific Dunes Nos. 4 and 13, and Ranch’s own No. 6. All of these holes blow No. 17 away in terms of both strategic intrigue and personality.

Bar a bunch of ghost trees lining the coast, this is — on the scorecard at least — a straightaway, 326-yard par four with no significant dune interplay. It’s got a great green, but this is a Coore and Crenshaw design, so of course it does.

If you’ve played Sheep Ranch, you already know the first step to turning No. 17 from pushover to prizefighter: There is a tournament tee right next to the No. 16 green, which turns the hole into a 420-yard monster. We all know it’s there, and we’re not allowed to play it (unless you’re playing alone because the threesome you were paired with canceled because they were tired…true story). It all comes down to resort-operator logistics. The back-tee distance doesn’t sound bad, but that’s into the traditional Summer wind. To hit from this tee to the current front tee is about 200 yards of carry, from which it’s about 225 yards in. The conservative line, requiring less cliff carry, still means hitting up and over an outcropping of stone and vegetation. This hole becomes a par 4.5 for quite a few people, and I’m sure Bandon has the analytics to demonstrate that it would be a slog.

But I’m still going to hold that the ban on the back tee is lame. If only someone had a formula for how such a stiff par four could still become a celebrated vanguard of strategic design. And if only that person was a remaining candidate for this exercise!

Lewis and Clark did not lead an expedition to the Pacific Coast for you to NOT take a tee shot from here. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

Lewis and Clark did not lead an expedition to the Pacific Coast for you to NOT take a tee shot from here. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

Yes, we’re converting the hole to the Road template (if you thought we were going to build a giant, artificial fairway 100 feet in the sky for a Channel hole, sorry to disappoint). From the tee, we invert the original Road’s blind shot a little bit — now it’s in the way of the conservative route. That such a “wall” exists here is a nice nod to the original, but is otherwise a coincidence.

Macdonald and Raynor have traditionally defined the strategic line with a hazard, as opposed to the original’s blindness. That hazard here, of course, is the cliff. The closer to the cliff your tee shot ends up, the better your line in. Basing this on the two Raynor Roads I’ve played, the green here is angled a bit more aggressively than the original Allan Robertson Road, enforcing a similar switchback strategy as what Ross employed above at Mayfield.

Granted, we’ll throw Mike Keiser and his retail golfers a break here: We’ve run the fairway to the back of this angled green so that players can choose to stay away from the cliff all the way home, so long as they’re willing to take at least three shots to get on. And you’ll note we didn’t indicate whether the hole’s signature pot bunker is sand or grass. We have a preference but…the course also has an unusual style guide.

Is this now the best Road hole at Bandon Dunes? Tom Doak might have thoughts.

Insert a dragon flying around the cliffs to maximize the potential. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

Insert a dragon flying around the cliffs to maximize the potential. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

What would happen if BERT WAY renovated NO. 7 at YEAMANS HALL?

You ever wonder why every advertisement features the tiny legal text at the bottom, and not the top? It’s because it’s the stuff in that legal text that will make you angry. You’re not actually getting six free CDs; you’re signing up to pay for CDs for the rest of the year. Anyway, that’s why I saved this entry for last: It will irritate more of my readers.

First, you’ve got the concept of altering a template and, in all likelihood, making it not a template anymore. And I’m not having Donald Ross do it, or some other icon…I’m having Bert Way do it. But let’s talk about the hole before we talk about the re-designer.

No. 7 is, appropriately — considering our last entry — the Road hole at Yeamans Hall. As with every other hole at Yeamans, the green is superb. The problem lies more with the body. My understanding of the Road template is that a hazard exists along the side where you want your tee shot to land. There’s a cross bunker, but it’s, at most, an 150-yard carry from the back tee. Meanwhile, it’s 215 yards from that tee to the first fairway bunker along the left (which features a much worse angle in). The only thing that scared me, not a power guy by any stretch, about aiming for the right side of the fairway was the prospect of hitting a member’s very expensive vehicle as it came down the adjoining driveway (true story).

Again, the green is better than the fairway. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

Again, the green is better than the fairway. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

So what can Way do to make the tee shot more strategic?

I’ll be frank: There’s not a lot to go on in terms of Way’s design background. His most famous original, Firestone’s South course, has since been reshaped to the point where it’s more accurate to call it a Robert Trent Jones. Our influence here comes from his work at Mayfield…but it might not even be his work, per se.

Way gets the lion’s share of the credit for Mayfield’s design, because it remained his home course for decades after it opened. It’s acknowledged that the original design, however, was done in hand with Herbert Barker, the one-time professional at Garden City Golf Club. This is relevant, because old aerials at Mayfield show several holes that feature what I call “zipper bunkering,” tight lines of geometric sand hazards, a style I associate with Devereux Emmet, who of course created the first rendition of Garden City (prior to Walter Travis’s work). What I’m getting at is that it’s quite possible that my recommendations for Yeamans Hall No. 7 might actually derive more from the stylings of Barker than Way. Still, Way had his chance to remove the bunkers during his tenure, but they were still there during the ‘50s. Tacit approval. Onward we go.

We’re going to remove all current fairway bunkers for a rethink. Starting at about 190 yards out, we’ll begin a line of four zippered bunkers along the right side. On the left, we’ll leave the land unsanded; theoretically, the angle of the infamous Road green (which we’ve left intact) should prevent GIR attempts from that side.

Here’s where it gets radical: Using the old version of Mayfield’s No. 13 as a direct inspiration, we’ve added an enormous cross bunker about 60 yards out from the center of the green. Two short rows of zippered bunkers create a runway onto the putting surface. The back hazard from Raynor’s rendition remains in one piece. This has always been a rather short “Road” hole, just 428 yards from the back tees, but the approach shot is uphill; the new cross bunker will have a “Great Hazard” effect, where those who don’t strike the ideal tee shot will need to think hard before trying to cross it in two.

Too extreme? Perhaps, but it’s also not entirely beyond the pale; The No. 5 “Alps” hole at Yeamans Hall features a quasi-similar question upon its second shot.

Somebody’s about to get an angry email. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

Somebody’s about to get an angry email. (Photo Cred: BPBM)