I’ve got opinions on what golf courses would most benefit from receiving a restoration from a qualified architect. As do you. We are both shocked when the rest of the world’s golf course architecture aficionados don’t prioritize the same projects that we do. The solution, obvious to anyone who has taken Statistics 201, is to create a larger sample size to determine what are truly* the most restoration-deserving courses in the United States.

We sent invitations to participate to a range of course architects, superintendents, professionals, journalists, and otherwise well-traveled armchair enthusiasts in order to hear their ideas. The result is this, a countdown of the 25 courses that these experts most want to see renovated or restored. This list comes from 255 total courses, nominated by a group of 76 experts.

All nominators were instructed that they could nominate, in order of preference, up to 10 courses. If ranked, point values were assigned via a semi-academic reflection of preference emphasis, based on existing literature (i.e., I took a less amateur-hour process than “ten points for your first ranking and one point for your tenth ranking”). In the case of a tie between courses at the end of the process, the total number of nominators served as a tiebreaker. All nominees were required to be:

- In the United States (i.e., no Highland Links).

- Not undergoing another restoration or renovation project currently (many are unaware of the current plan in place for Kankakee Elks, but there is one).

- Exist in a location where reconstruction is possible (i.e. Flushing Meadows would be amazing, but it’s impossible. No Sand Valley Lido-style rebuilds allowed here).

- There was no prescribed method for what changes would take place at the course. They could be restorations, renovations, or Andrew Green-at-Congressional reorganizations.

*Will you be angry about this list? Yes, inevitably. After all, both GOLF and Golf Digest create their course ranking lists, and we as a community hate them in spite of their efforts. This list will no doubt create similar reactions among ye.

So here we go. The 25 courses that would benefit most from reno/restoration, according to the people:

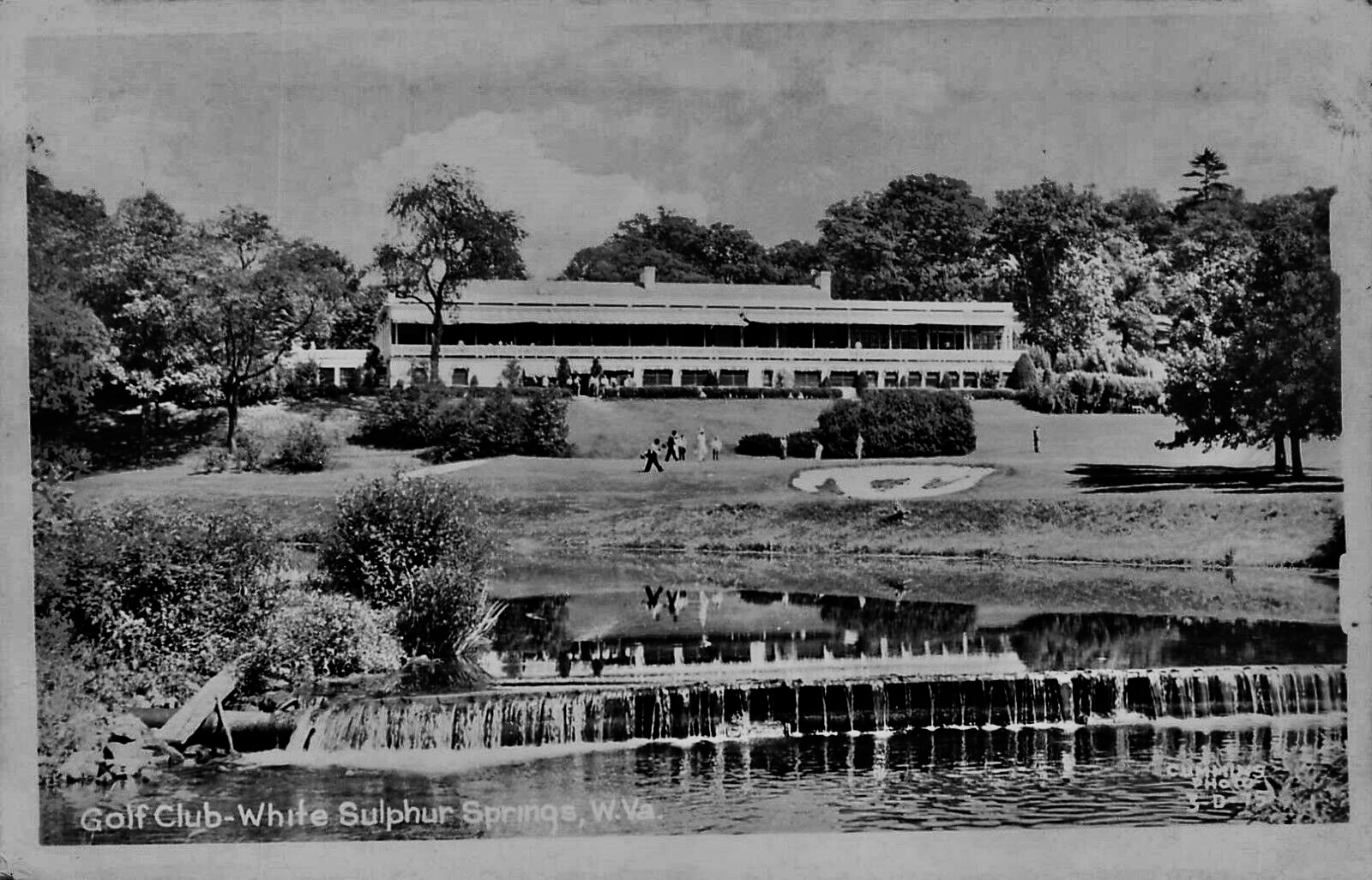

A look across to No. 18 at Old White during the early ’50s. Not the version of the hole that panelists want to see, of course. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

A look across to No. 18 at Old White during the early ’50s. Not the version of the hole that panelists want to see, of course. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

25. The Greenbrier (White Course)

Charles Blair Macdonald / Seth Raynor

“They’ve never quite gotten it right.” – (These quotes come from feedback from the panelists.)

There are renovation projects that have fallen into disrepair and then there are renovation projects that have not. The White Course at Greenbrier Resort is clearly in the latter category. It’s a more surprising entry into that latter category than other courses you’ll see on this list, perhaps, because it’s taken steps, as recently as a decade ago, with a firm generally well-regarded for its restorative work (Keith Foster). Based on the comments of several panelists, the Macdonald original (with Raynor updates) still doesn’t quite hit the spot during 2024.

The problem may not be as simple as boxing Foster in as a Tillinghast specialist. At the time of his work, the resort looked forward to a long history with the PGA, plans that have since dissipated. While that will certainly give the resort the time to focus on a full restorative effort, but the current rack rate to play White doesn’t put much economic onus on such work. Perhaps the headlines and eventual ticket prices for Yale, might incentivize Greenbrier to pursue such a project.

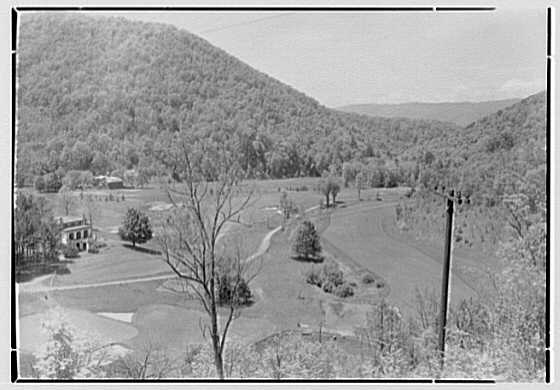

Not the most exciting portion of The Homestead’s Cascades course, but the original size of the greens can be seen here at nos. 17 and 18. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

Not the most exciting portion of The Homestead’s Cascades course, but the original size of the greens can be seen here at nos. 17 and 18. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

24. Homestead Resort (Cascades)

William Flynn

“[Flynn’s original plans] are unreal.”

We move elsewhere in Appalachia to another well-heeled resort that is overseeing another Golden Age-dated course. The quote from our anonymous panelist, in this instance, refers to William Flynn’s original designs for the course. That tone leaves lesser Flynn fans filled with curiosity for what could be at this Shenandoah property.

The bad news is that Omni’s Homestead resort is humming along happily, meaning less incentive for a dramatic overhaul. The good news is, first, that this resort doesn’t need to worry about planning around a PGA event. The further good news is the club has been implementing fairway-widening and tree-clearing program masterplanned by Flynn czars Wayne Morrison and Thomas Paul. That the club has already shown its willingness to hire outside experts to handle restorative work at its celebrated courses (e.g., Forse/Nagle for the Tillinghast/Donald Ross design at Omni Bedford Springs) is also a positive. And, if we’re getting aspirational, the brand is benefitting nicely from hosting a Gil Hanse at its new Frisco location. The same Hanse who is coming off a celebrated restoration at Flynn’s Country Club near Cleveland. Just saying.

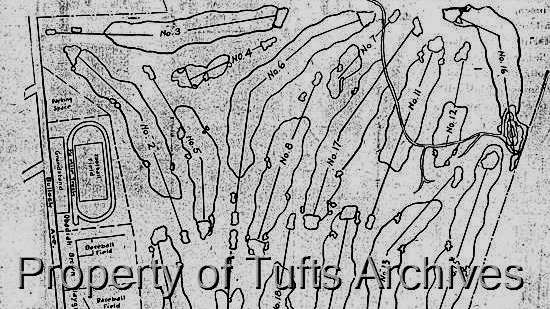

This routing, which is the property of Tufts University, in case you hadn’t heard, shows details of the north half of Triggs. Of particular note to me is the version of the par three at No. 12. (Photo Cred: Tufts University)

This routing, which is the property of Tufts University, in case you hadn’t heard, shows details of the north half of Triggs. Of particular note to me is the version of the par three at No. 12. (Photo Cred: Tufts University)

23. Triggs Memorial

Donald Ross

“Beaten like a rented mule, but such a solid site for quality walking golf. Could be quite good!”

Perhaps no golf course architect’s legacy has benefited more from the current wave of restorations than Donald Ross. Although the work done at his public options, such as Pinehurst No. 2, have been nice, there are a wide range of municipal courses from Ross’s pen that stand for some TLC. Triggs Memorial misses out on some attention because, like Providence itself, the biggest New England city tends to hog the spotlight. George Wright was, perhaps aspirationally, voted as one of the Top 100 public golf courses in the United States.

There’s not a lot holding back Triggs from being George Wright. The terrain at the only public Ross in a state full of well-designed Rosses is every bit as deserving of your critical attention. The Rhode Island Golf Association had restoration plans in mind but lost out on a 2023 bid to run the course. The idea remains alive.

Here’s one version of what Montauk Downs could be, depending on whose version you wish to pursue. This aerial comes from 1930. (Photo Cred: Suffolk County, NY)

Here’s one version of what Montauk Downs could be, depending on whose version you wish to pursue. This aerial comes from 1930. (Photo Cred: Suffolk County, NY)

22. Montauk Downs

H.C. Tippet / Robert Trent Jones

“I’d just like to test my hypothesis that there is a better RTJ Sr. restoration architect out there than one of his sons.”

Is the golf course architecture universe’s demands for course restoration limited to the Golden Age? Depending on how you interpret nominations for Montauk Downs State Park…maybe. On one hand, many are eager to hold out the New York state municipal as one of Jones’s better designs, through his work to create the private Montauk Golf and Tennis Club (which was eventually purchased by the state during 1978). That said, the original course on the property, from the pen of H.C. Tippet, included significant bunkering.

Either way, the current state of the course owes its presentation, as alluded above, to Rees Jones. There’s little doubt that his well-televised renovations at Bethpage Black earned him the keys to bring a similar, if less aggressive, tone to Montauk Downs. Regardless of whether they prefer the version of Tippet or Robert, our panelists have implied that they don’t prefer the Rees version.

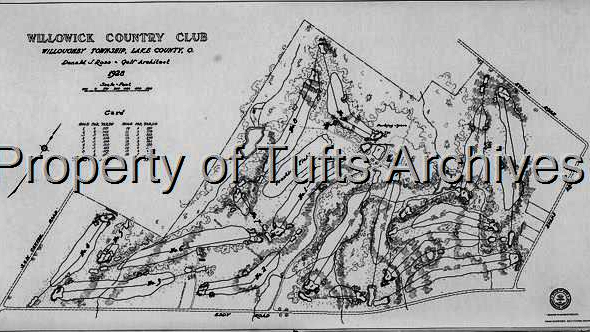

More Tufts love, this time reflecting Manakiki as it was known during Ross’s era, as Willowick Country Club. (Photo Cred: Tufts University)

More Tufts love, this time reflecting Manakiki as it was known during Ross’s era, as Willowick Country Club. (Photo Cred: Tufts University)

21. Manakiki

Donald Ross

“I don’t think any city has more potential from a municipal perspective than Cleveland.”

Hope you don’t tire easily of Donald Ross municipal courses. The city of Cleveland was once blessed with two, but the less-acclaimed of those, Acacia Country Club, has since been reclaimed by nature. That said, many Ohio course architecture enthusiasts argue which of Cleveland’s other two big-name munis would truly be the best public golf course in the state if given a proper restorative treatment. The Ross entry, Manakiki, gets this writer’s vote.

There’s reason for hope. The city has turned Highland Park Golf Course over to a nonprofit group, which has introduced both capital and design improvements. Although Highland Park doesn’t have nearly as sexy a course history as Manakiki, this is a similar setup to what we’ve seen occur at courses like Memorial Park in Houston, and the developing Cobbs Creek project in Philadelphia. If it works well by the city’s reckoning, it may open up its more acclaimed properties to the same model.

I struggled to find a good image for the original state of Northwood. Regardless, it’s probably even more glorious than modern photos make it seem. (Photo Cred: Northwood Golf Club)

I struggled to find a good image for the original state of Northwood. Regardless, it’s probably even more glorious than modern photos make it seem. (Photo Cred: Northwood Golf Club)

20. Northwood

Alister MacKenzie/Robert Hunter

“Easy to see the grassed-in bunkers and lost green shapes. Wouldn’t be terribly hard to improve a charming family spot.”

One of our nominators made a tongue-in-cheek reference when citing Northwood as a candidate for restoration, suggesting a major tree-clearing program. Their comment touches upon what’s both Northwood’s biggest asset and its biggest problem: It’s defined by trees. Rest assured, the redwoods that line the fairways here are indeed an asset; even those less obsessive regarding strategic architecture have seen the mesmerizing images on social media.

The problem is that those trees are enough for many visitors, hiding the Alister MacKenzie / Robert Hunter design that weaves between them. Those familiar with MacKenzie’s work in California know that he left few poor designs in his wake. A restoration of his greens and bunkers, as suggested above, might take this from a quirky gem to one of the better nine-hole options in the nation. No tree clearance necessary.

Enjoy the National Golf Links of America? You may not even be aware of Women’s National, which is lurking beneath Glen Head Country Club. (Photo Cred: Glen Head Country Club)

Enjoy the National Golf Links of America? You may not even be aware of Women’s National, which is lurking beneath Glen Head Country Club. (Photo Cred: Glen Head Country Club)

19. Glen Head

Devereux Emmet

“It doesn’t just need history to be worth the work.”

Does a golf course restoration require us to reinstate its original name, as well? Perhaps not, but the original name of Glen Head Country Club might offer some context for this course’s importance in American golf. To be fair, “Glen Head Country Club” was its original name, before Marion Hollins and her group of investors took control and redubbed it “Women’s National Golf and Tennis Club.”

No doubt she played some role in commenting on the course’s design, as she did at Cypress Point, Pasatiempo, and others. Her employees in this project include a who’s-who of American architects—although Devereux Emmet receives most of the credit in modern publications, there’s evidence that William Flynn procured his services, and both Macdonald and Raynor offered consultations. Unfortunately, it seems Hollins heading west hurt the club’s well-being. It was soon absorbed into The Creek Club and then spun off once again, to become “Glen Head.”

Yet another Long Island club that would stand among giants with just a touch of elbow grease.

Being proud to have Jack Nicklaus as an alum and possessing an Alister MacKenzie design are not mutually-exclusive. (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

Being proud to have Jack Nicklaus as an alum and possessing an Alister MacKenzie design are not mutually-exclusive. (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

18. Ohio State University (Scarlet)

Alister MacKenzie/Perry Maxwell

“Nicklaus’s work at Ohio State has resulted in a facsimile of something great.”

Ohio State alums tend to blow what they have out of proportion, and unfortunately the same applies to its golf campus. Depending on who you ask, the university currently has two Alister MacKenzie designs in its portfolio. The Gray was no doubt routed by MacKenzie but some deep digging has shown that its design is more accurately attributable to a professor at the university. There is no doubt as to the Scarlet’s lineage but as you’ve no doubt heard, perhaps the great architect’s final design has since been significantly renovated by Jack Nicklaus.

Despite the dramatic quote presented by a panelist, the work done by Nicklaus is not quite as damning as some suggest — only one hole (No. 4) is totally alien from MacKenzie’s routing. Unfortunately, this course is probably a long way from restoration. Nicklaus is arguably the most-revered athlete in the history of a university that takes its athletics too seriously (I’m an alum…I can say it). The idea of it moving one shovel-full of dirt less than two decades after its last big project, much less while Nicklaus is alive, is a long shot.

Nearly three-decades beyond the work done by Langford and Moreau, the duo’s signature shaping is still far more evident. (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

Nearly three-decades beyond the work done by Langford and Moreau, the duo’s signature shaping is still far more evident. (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

17. Clovernook

William Langford/Theodore Moreau

“This should be the private club equivalent of Lawsonia.”

I spend a significant amount of time trying to raise awareness for Donald Ross’s oft-ignored Cincinnati gems but, to their credit, a great deal of others are more focused on celebrating the Langford and Moreau little-known that happens to be more near to my family homestead. Clovernook Country Club has, for its lack of room to grow, remained relatively under-the-radar at a national level.

Its growth has come in the expected, unpleasant way…trees. Shrinkage has occurred everywhere else; old aerials show fairways stretched to their logical maximum for the employ of width ‘n’ angles, and both putting surfaces and sand hazards at a scope more expected from fans of Lawsonia. It’s one of the few remaining private clubs on Cincinnati’s west side, and is among the more blue-collar clubs in the city as well. This is to its credit, but it may mean little liquid assets to throw toward a significant restoration program. Sam Beckman and David Savic did some Moreauvian terrascaping at the beginning of the century, getting bunkers down from being level with the greens, but legions of trees beckon for felling.

An old-fashioned aerial from 1921, much, much nearer to the Walter Travis original. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

An old-fashioned aerial from 1921, much, much nearer to the Walter Travis original. (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

16. Columbia

Walter Travis

“Old photos of the place are awesome. The current course is a total dud.”

There’s demand for Walter Travis in the nation’s capital—most know about the municipal option at this point, but some might be surprised to learn there’s GCA-aficionado discontent with one of the city’s most celebrated private clubs as well. Columbia has had many famous hands on it throughout the years but, based on feedback, the result is a muddle, where the ideal product would point more directly to Travis’s involvement and enjoyment at Columbia. Old photos reveal the old man’s signature features, such as chocolate drops dotting the landscape.

Joel Weiman’s recent master plan was seven years in the completing, which might suggest it will be a minute before this old-money club will want to tap new blood. Still, even if the city’s muni megaproject is held up, the clubs are making moves, namely at the hands of Andrew Green. He won acclaim for his aforementioned overhaul at Congressional, and rumors are that he’ll be at Chevy Chase soon. He doesn’t need to mount a trifecta, but Brian Schneider’s recent work at Travis’s Hollywood might give Columbia something to aspire to.

Yes, there’s a plan. Will Washington D.C. allow the National Links Trust pull the trigger? (Photo Cred: National Links Trust)

Yes, there’s a plan. Will Washington D.C. allow the National Links Trust pull the trigger? (Photo Cred: National Links Trust)

15. East Potomac

Walter Travis

“Reversible Travis…duh-duh, duh-duh…DUH-DUH!”

Don’t worry…I wasn’t going to let you wait too long, just in case you weren’t actually aware of the Walter Travis D.C. muni mentioned above. The choice to include East Potomac on this list merits some smooth-talking on this writer’s part because, in defiance of the rules laid out at the top of the page, there is a plan in East Potomac in place. Two items justify its inclusion, however. One, the National Park Service doesn’t seem close to getting Tom Doak’s plan approved. Two, there must be a reason why — of the three courses in play here — our panelists chose overwhelmingly to highlight Travis’s work at East Potomac.

The first reason, if the shared quote above is any indication, is the course’s reversible intent. Many routes are designed with the Old Course in mind, but the well-read Travis meant this muni to mimic its inspiration in St Andrews. Until we get concrete news from the NPS, East Potomac belongs on this list.

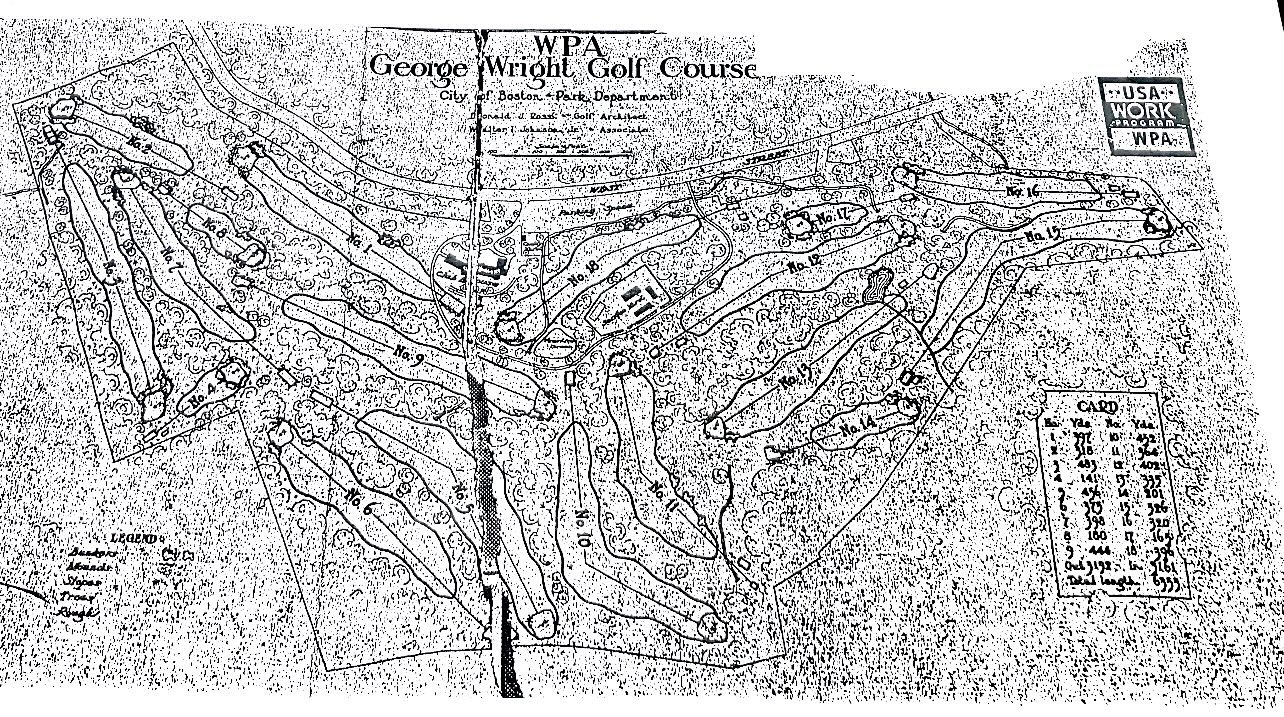

Wright is might among Donald Ross’s large collection of municipal offerings. (Photo Cred: (Working on this one))

Wright is might among Donald Ross’s large collection of municipal offerings. (Photo Cred: (Working on this one))

14. George Wright

Donald Ross

“If restored fully, George Wright would be, in my opinion, the best municipal course in the country.” -Andy Johnson

The above quote gets attribution because it wasn’t made as an anonymous panelist, but was published within a similar exercise carried out by The Fried Egg. Anyone who can pick up just a whiff of context whilst reading this realizes that I personally might have another municipal in mind, but this quote gives credence to its potential. Johnson isn’t the only expert to pay Wright’s quality forward. GOLF has a tendency to favor Golden Agers prior to any work being done (e.g., previously featuring Yale in its world Top 100) and this one already appears on the publication’s Top 100 U.S. publics.

In a world full of deserving Ross municipals, George Wright may be the best, with its land movement and exposed rock, reminiscent of the region’s most celebrated clubs. Outside of Pinehurst, perhaps no city showcases Ross’s abilities as extensively as Boston. Restoring the one left for the general public would be more meaningful than most.

It’s important to note that Mark Mungeam has been working consistently to bring Wright back from a brink, and all suggest that his work should be well-received. The sheer number of nominations suggest a more comprehensive program would be a godsend, and there’s no reason why Mungeam shouldn’t be at the helm, budget-permitting.

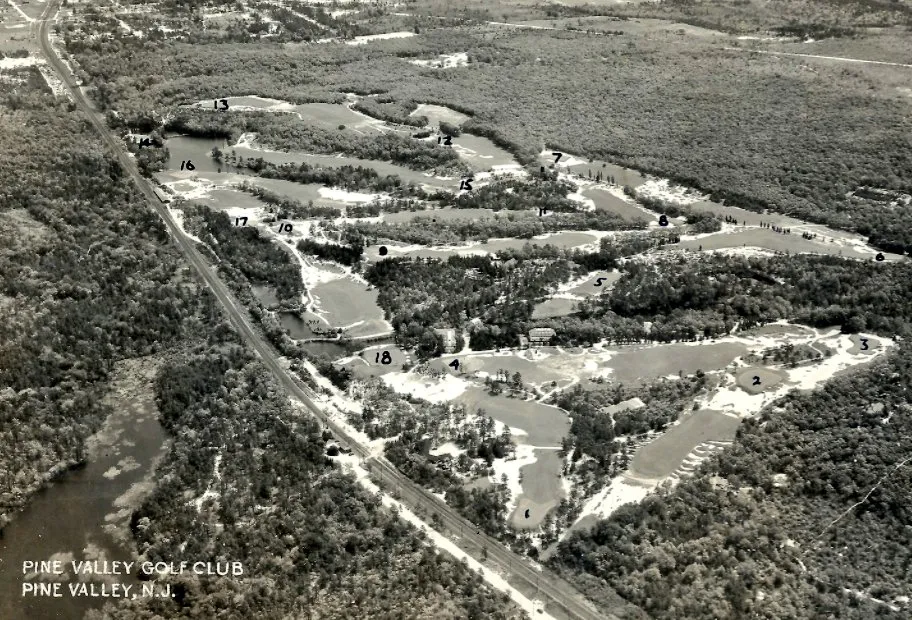

To be fair, the difference between modern Pine Valley and ye olde Pine Valley isn’t so obvious from the air. Get nearer to see the small details. (Photo Cred: (Working on this one))

To be fair, the difference between modern Pine Valley and ye olde Pine Valley isn’t so obvious from the air. Get nearer to see the small details. (Photo Cred: (Working on this one))

13. Pine Valley

George Crump/Everyone

“I saw the No. 2 green in the late ‘90s. Who messes with that?”

It is at this point in the rankings where the truly-interesting conversations in GCA corners begin, where the conversation about what must be done begins to stall as competing parties debate whether anything should be done at all. Pine Valley is already held by GOLF as the world’s best golf course. That suggests to the everyday observer that any changes made must be minimal in nature, right? Quite the contrary.

Few courses feature bunkers as notable, or as sizable, as Pine Valley. Those hazards offer ample tinder for praising it as the peak of strategic golf course architecture and, often in the same breath, how their presentation is a mockery of its potential. Even were that argument to subside, the club’s signature tree hallways, intentional greenery that is rare in that it accomplishes its goal of preventing views to other holes without constricting the intending playability. Would a new plan justify their removal, or justify their existence?

Not helping anything is that the most popular lightning rod in modern course architecture conversations, Tom Fazio, is both consulting architect and a member. The former is a job that has the potential to stay in the family.

That no one reading this would pass up an invitation to play Pine Valley is a testament to how difficult selling a restorative effort would be.

Ryan Farrow’s splendid graphic shows exactly where Tillinghast’s Bethpage Black differs from Rees Jones’s. (Photo Cred: Ryan Farrow)

Ryan Farrow’s splendid graphic shows exactly where Tillinghast’s Bethpage Black differs from Rees Jones’s. (Photo Cred: Ryan Farrow)

12. Bethpage State Park (Black)

A.W. Tillinghast

“If restored and renovated fully, Bethpage Black would be, in my opinion, the best public course in the country.”

That panelist quote comes, to no surprise, from your correspondent, by replacing a few of Andy Johnson’s words regarding George Wright. Bethpage Black’s current world rankings are a poor reflection of just what could be possible at Black, currently a showcase for the penal school of golf course architecture. I choose to emphasize both “restored” and “renovated” here—while Rees Jones’s renovation chose to not include nearly 28 acres of fairway from Tillinghast’s original design, the current lackluster greens are not on him. Although I draw journalistic issue with Ron Whitten’s attribution of Black to Joseph Burbeck, I believe there’s reason in the timeline to surmise that the superintendent was forced to handle the putting surfaces when Tillinghast was fired abruptly. A new set of putting surfaces, to complement Tillinghast’s original fairway specs, could make this the best public golf course in the country.

Those current world rankings give little reason for the park to consider a reformation, however. It has people sleeping in a parking lot to play, and it sells approximately one gazillion-dollars-worth of merchandise that features the stupid “this course is tough” sign (not a Tillinghast original).

For all the Ross munis featured on this list, the lack of similar entries from Tillinghast’s oeuvre is a touch disappointing. But at least our panelists know the big one can be better.

Cross the ravine from the North course and you’ll see what was once Torrey Pines’ South. (Photo Cred: University of California San Diego)

Cross the ravine from the North course and you’ll see what was once Torrey Pines’ South. (Photo Cred: University of California San Diego)

11. Torrey Pines (South)

William F. Bell

“Build better holes and utilize the ocean better.”

And, in case you don’t agree with either Johnson or myself, here’s another slice of prime municipal property awaiting reconstruction. The South course at Torrey Pines is a rarity on this list in that the average panelist is not prioritizing a restoration over some other effort (e.g., a full redesign). There is no doubt that Pines owns perhaps the best location in the United States for a municipal golf course. What that golf course should look like, on the other hand, could be left to the imagination of a modern architect.

This redesign may be more likely than we realize, if you—like me—believe that the city of San Diego takes the appeal of its most popular course seriously. Torrey Pines hosted two U.S. Opens, and the likelihood of a third seems mooted, unless you believe the USGA will offer the next spot, 2043, to a second-consecutive coastal California public. That said, the PGA Championship docket remains relatively wide open, and San Diego should have seen the writing on the wall. Gil Hanse has restored and designed major hosts for both the USGA and PGA of America, so it’s not too much to think Torrey could target a big name to modernize its premiere property, despite recent work from Rees Jones.

You’ll see the University of Michigan’s most-famous green about one-third over from the left. (Photo Cred: University of Michigan)

You’ll see the University of Michigan’s most-famous green about one-third over from the left. (Photo Cred: University of Michigan)

10. University of Michigan

Alister MacKenzie

“I hope they steal a sign from Yale and allow for a well-funded restoration, as it could easily be in the top two campus courses in the country.”

Ugh. Nothing like a well-informed panelist suggesting that your undergraduate rival’s (Michigan) campus might have the second-best college course in the nation, second only to your graduate rival’s (Yale). Unfortunately, Michigan beat Ohio State to the punch and hired MacKenzie when he was less near-to-death and, if the bones on the ground are any indication, when he was quite full of life indeed.

I think it’s reasonable to believe that Michigan will also beat Ohio State to the restoration punch. First, it’s not a pain point to erase problematic renovations when they come from a Michigan State alum (Arthur Hills) versus Ohio State’s alum, who happens to have the most major wins in history. Second, after a national championship, those dummies up north are probably willing to park farther from the stadium. Third, and this remains entirely a rumor until I find out more, there may already be wheels in motion to attract a pair of big names to restore/renovate both Michigan and its Radrick Farms course. Fingers-crossed.

Ah, but will Ojai be willing to restore its carts as well? (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

Ah, but will Ojai be willing to restore its carts as well? (Photo Cred: Library of Congress)

09. Ojai Valley Inn

George Thomas

“Some things you can’t get back but taking it back as much as possible would be great.”

The “things you can’t get back” referred to above is the original No. 6 hole, which currently sits under a relatively-recent hotel addition. There are very few universes where a resort decides to demolish buildings for the sake of a course restoration. Ojai Valley Inn is not Sand Valley Inn…the average attendee is not here for golf. The lack of completeness shouldn’t undermine the value of a proper restoration carried out along the rest of the property. From all involved, such work would add polish to a gem in Thomas’s course collection, which is much smaller than the other architects featured in this list.

Although many may stand by the maxim that a restoration is a restoration, dammit, there’s hope to be had in the potential for new holes added to Golden Age restorations. Although there wouldn’t be room for a relocated No. 6 per se (a la Hanse’s relocation of MacKenzie’s lost par three at Lake Merced), a talented architect could presumably find a place for an eighteenth hole (sorry renegades…there’s no way a resort agrees to 17 holes at its singular golf course). I’m not intimately familiar with Ojai’s topography, but I was keen on Forse and Nagle’s new No. 18 Davenport, which fit within Alison’s remaining 17 quite nicely.

Garrett Morrison did a higher-quality overview of the club at The Fried Egg.

Perhaps Stanley Thompson’s best course in the Americas, if you define “Americas” as “only America.” (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

Perhaps Stanley Thompson’s best course in the Americas, if you define “Americas” as “only America.” (Photo Cred: Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

08. Sleepy Hollow (Ohio)

Stanley Thompson/Howard Hollinger

“Cleveland arguably already has Thompson’s best non-Canadian course. It could cement that legacy.”

A debate between Cleveland’s best municipal course is more enthusiastic than for most other cities. Although your correspondent prefers Manakiki (no. 21 on this list), a greater portion of golfers prefer Stanley Thompson’s Sleepy Hollow, which is just fine. A subconscious theory as to why may rest in the relative rarity; we’ve seen three Ross municipals on this list already, and Ohio doesn’t lack for designs from the Scot. His Canadian counterpart has more courses in Ohio than any other state, more than 75 percent of his American work, a fact that Cleveland could lean on in taking up a project involving Sleepy Hollow.

Does this course live up to our panelist’s description above? The only asterisk is that Thompson only designed ten of the current holes (nos. 1-9 and no. 12), but fortunately the original architect, area pro Howard Hollinger, did no shoddy job. Among his contributions is the semi-famous “chasm” hole at No. 14. As mentioned in the entry for Manakiki, Cleveland seems to be exploring alternative municipal management formats. If it leads to a restoration at either of its prize holdings, it will be a victory.

OK, so this is a modern aerial of Spring Valley, because the USGS aerials aren’t so great. Even nearly a century after Langford and Moreau left, you can see the imprints. (Photo Cred: Google)

OK, so this is a modern aerial of Spring Valley, because the USGS aerials aren’t so great. Even nearly a century after Langford and Moreau left, you can see the imprints. (Photo Cred: Google)

07. Spring Valley (Wisconsin)

William Langford and Theodore Moreau

“Hidden gem in southern Wisconsin has all the hallmarks that the dynamic duo are so well-known for (except for sand in the bunkers!).”

An increasingly rare occurrence is that of the owner who doesn’t realize that they’re sitting on a historically-significant golf course. That may yet be the case at the aforementioned Clovernook, as it relates to the course’s Langford and Moreau design. That is not the case at Spring Valley. “Anyone who has played Lawsonia, ranked in the Top 100 public courses in the U.S. can see the similarities,” claims the course’s site.

Indeed, even on Google’s foggy modern aerial, you can get the idea for the original scope of the duo’s signature putting surfaces. If you don’t see them, it’s likely due to the total lack of bunkering, which disappeared over the past century. Based on feedback from panelists, and architects in particular, Spring Valley would be an immediate success. Both Wisconsinites and Chicagoans are already aware of Lawsonia—to have a second version within an hour of Milwaukee and Chicago seems like easy money.

Many of the courses in the top 10 of this list may be obvious, passé. Spring Valley might be the most eye-opening in terms of the genuine demand from GCA’s most passionate individuals.

Coming into Sawgrass’s No. 9 hole, circa 1986, when some of the gator’s teeth were already starting to be pulled. (Photo Cred: ‘Golf Courses of The PGA Tour’ by George Peper)

Coming into Sawgrass’s No. 9 hole, circa 1986, when some of the gator’s teeth were already starting to be pulled. (Photo Cred: ‘Golf Courses of The PGA Tour’ by George Peper)

06. TPC Sawgrass

Pete Dye/Alice Dye

“The rugged look of the 1980s was vintage Pete Dye.”

The estate of Gabriel Garcia Márquez recently released his “final” novella, a text he specifically requested they not do. It’s a philosophical and ethical argument, if there ever was one. Does the creator’s intentions take precedence over everything, or should bettering the lives of his millions of fans (a bit of an exaggeration, I know) outweigh his personal wishes? Pete Dye expressed his disinterest in restorations as a concept, so how much should we respect those wishes?

Not going to beat around the bush on this one: We ignore Dye. First, unlike in the Márquez case, a renovation of TPC Sawgrass isn’t tied to his descendants cashing in. Second, again unlike the anecdotal example, the PGA owns the course. Third, we’ve seen enough trimming and adjustments at Sawgrass, both under Dye’s eye and other eyes, that we don’t need to have this argument anymore. The game (if not the Tour) has moved on. The only thing the PGA could do to make The Players anything like Augusta is by selling affordable concessions. Cancel the videos of the legion-sized maintenance crews, and instead create a master plan for growing.

I’m not getting my hopes up, but the GCA community might be.

A whole lotta sand going on, with two very famous par threes along the eastern shore. (Photo Cred: Suffolk County, NY)

A whole lotta sand going on, with two very famous par threes along the eastern shore. (Photo Cred: Suffolk County, NY)

05. Timber Point

C.H. Alison

“Incredible potential here. Property intact, political will lacking.”

Long Island’s golfing wealth among private courses is well-established. This list highlights how deep its municipal offerings could run—neither Montauk Downs nor even one of Tillinghast’s Bethpage offerings tops the list for desired renovations. That ribbon goes to Timber Point, a C.H. Alison design that was once perhaps the most private 18 on the island. By good fortune, Suffolk County acquired the course during down years and, by less good fortune, its muni masters expanded its offerings to 27 holes for more play.

Two things make this a compelling restoration. Like the Lido before it, Timber Point has at least two legendary holes to its name, its “Harbor” and “Gibraltar” par threes, not to mention the rest of the original Alison design for traveling course enthusiasts to drool over. The second compelling argument is the potential involvement of Harry Colt at Timber Point, which would make it the only publicly-accessible course in the United States from one of the world’s great architects (admittedly, as with any North American course that claims Colt heritage post-1914, there’s some skepticism to be had).

A bigger hurdle would be demand: Suffolk County could pull a Memorial Park and charge outsiders considerably more than what it asks locals, but there would ultimately be nine-fewer holes to offer to those same locals.

Does anybody know who did this routing for the original Sharp Park? I legitimately don’t know. It’s seemingly modern, yet features holes since lost to the tides. Seriously, let me know. (Photo Cred: See caption.)

Does anybody know who did this routing for the original Sharp Park? I legitimately don’t know. It’s seemingly modern, yet features holes since lost to the tides. Seriously, let me know. (Photo Cred: See caption.)

04. Sharp Park

Alister MacKenzie

“What once seemed impossible now has some chance of getting a restoration and returning the MacKenzie glory.”

Despite finishing fourth in this ranking, Sharp Park is perhaps the definitive entry because it best summarizes the trends set forth by our panelists. Of the 25 courses seen here, a whopping 18 are publicly-accessible. Of those, 10 are municipally-operated (Sharp Park is the highest-ranked of those 10). Finally, this collection reflects the range of talent present during the “Golden Age.” Twenty-two of these courses hail from that era, by our definition, and that subset were designed by 12 different “firms.” It’s telling that even among this diversity, five separate MacKenzie courses received nominations and recognition within our top 25.

As with Ojai Valley Inn, the original 18 don’t hail strictly from the master’s pen. Twelve holes remain; weather issues erased the opportunity to save four of those, but two have been redesigned in corridors that once held MacKenzie originals. Again, I’ve got hope that a well-informed architect could restore MacKenzie’s originals while thematically tying in the new additions. Unlike Ojai Valley Inn, there’s a grassroots force behind this one. First, it’s at the top of the list for the San Francisco Public Golf Alliance, a nonprofit. Second, Tom Doak and Jay Blasi have already contributed work (if not the full restoration we’re looking for here). Finally, Blasi’s recent work proved his value as part of the city’s First Tee restoration of Golden Gate Park.

The only thing standing in the way is San Francisco bureaucracy…which, admittedly, is terrifying.

Looking out across the relatively expansive Riviera of 1938. The largest hazard at the famous No. 10 is at the left. (Photo Cred: University of California.)

Looking out across the relatively expansive Riviera of 1938. The largest hazard at the famous No. 10 is at the left. (Photo Cred: University of California.)

03. Riviera

George Thomas

“They have really messed up a couple of those holes.”

Forgive me for, perhaps, understating the qualifications of the final courses featured in this list. Odds are that you could list them prior to opening the post. Do you need me to reassert how Thomas took a far less impressive piece of land than the majority of these entries, and let the pure architect within him work wonders? No, probably not. Geoff Shackelford can, and will, tell you about it at least once a year, when the Genesis Open returns to the club.

Another thing that you hear about during that same week makes this restorative effort an interesting one. Kikuyu. Notoriously sticky, and adverse to the ground game that is so celebrated by the vast majority of those who would push for such a restoration. The turf type was certainly not in place when Thomas left—the most common theories are that it either spread from the property’s polo fields, or down from the hillside where it was used as an erosion-prevention mechanism. The herbivorous friction is so grating that it’s a rare instance where PGA player complaints might be valid. Wholesale kikuyu removal has been done before, as seen in Kyle Phillips work at nearby Hillcrest. Hillcrest, of course, doesn’t host an annual PGA event, where fears of escalating scores are always fodder for panic.

As a note, none of the panelists who nominated Riviera mentioned kikuyu. That’s my personal gripe. Many referenced the bunkering specifically, specifically citing Gil Hanse’s work at Thomas’s Los Angeles Country Club in terms of the potential here.

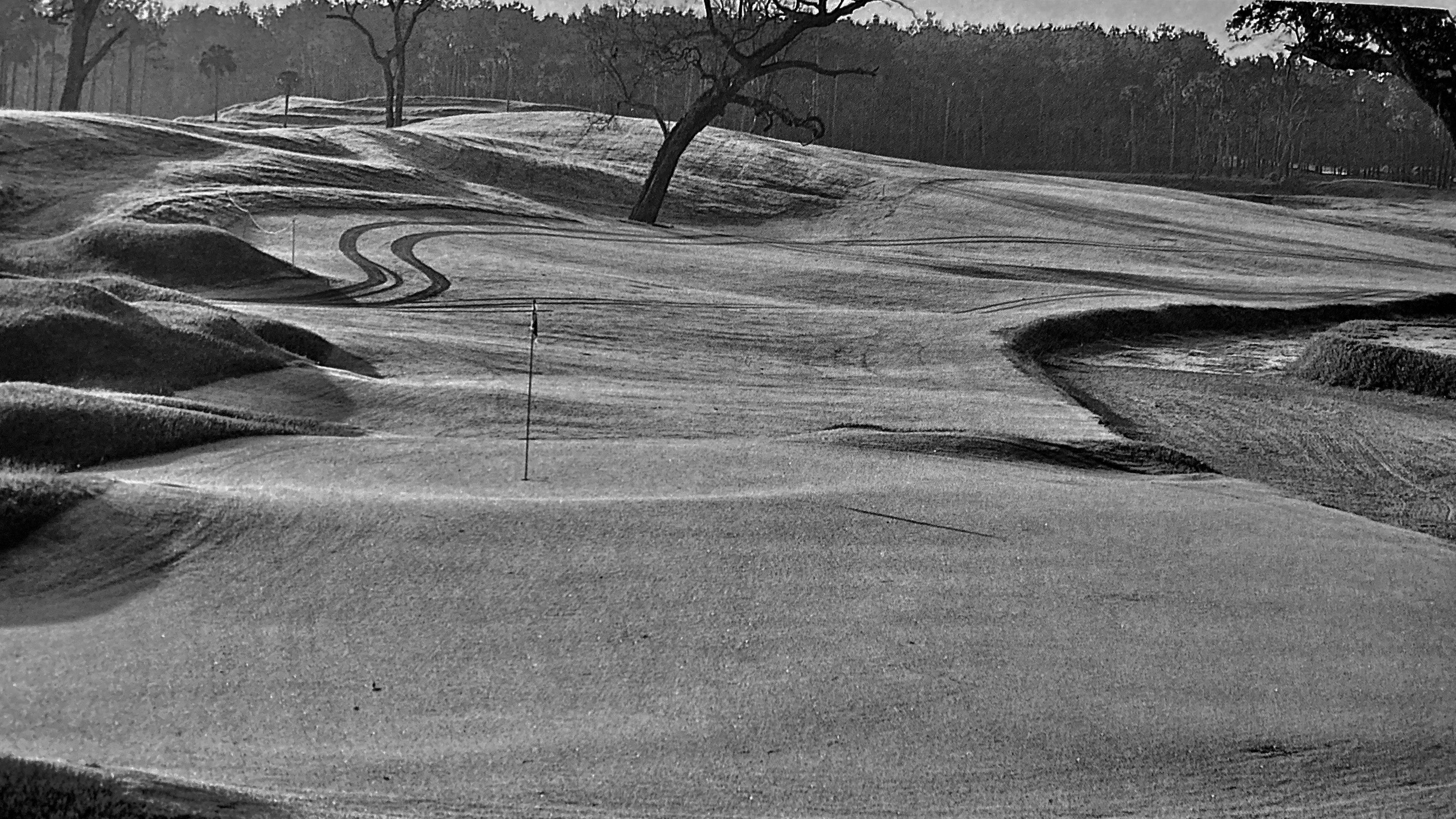

You no doubt saw this one a million times on Twitter this past week. (Photo Cred: I need help with this one.)

You no doubt saw this one a million times on Twitter this past week. (Photo Cred: I need help with this one.)

02. Augusta National

Alister MacKenzie

“When greens committees make changes to their course, they are undeniably implicitly swayed to make the course look more like Augusta…undoubtedly, if Augusta changed the course plenty of clubs would follow.”

Augusta National was the second-most cited course among the panelists, and at least one realized why, perhaps, it deserves to be at the top of the list. It’s not just a question of whether MacKenzie’s original course would be a significant improvement over the current iteration (it would be) but the impact that the decision to restore would have on the world of golf course architecture. Ask a GCA aficionado what the world’s most influential golf course is, and they are likely to suggest the Old Course. Ask any other golfer, the vast 98 percent, and Augusta will be the answer.

Grating words and phrases, such as “lush” and “no blade of grass out of place” spring from the fool’s errand of matching Augusta’s aesthetic. And poor, unfortunate souls the world over — not just in the United States but especially in markets where golf should most look to grow — seek to emulate these very factors. If you’re reading this, you’re likely similar to me in how you perceive Augusta’s trees, bunkers, and even, in some instances, greens. The people not reading this probably don’t. A post such as this won’t convince them of what the world’s greatest golf courses, or their club, should look like. But if it were to appear on TV? Then they’d pay attention.

As to what that final product would look like? That’s a much more interesting question than many realize. For instance, No. 9’s notorious boomerang green looks pretty awesome, but does it actually function well for the approach shots it serves (an honest question; I don’t know). Derek Duncan wrote an interesting piece this year on the “greatest” version of Augusta, which reminds us that “restoration” and “original” are not necessarily one-to-one.

No. 4 at Pebble Beach during Chandler Egan’s wilder days. (Photo Cred: University of California)

No. 4 at Pebble Beach during Chandler Egan’s wilder days. (Photo Cred: University of California)

01. Pebble Beach

Jack Neville/Chandler Egan

“But can you imagine?”

Imagine is the ideal word, on numerous levels. First, there is the steep task of convincing one of the world’s most iconic courses to shut down its money-making machine when the current product easily fills its tee sheet. Anyway, that’s the bad news first.

More relevant is imagining what Pebble Beach could be, another thought experiment that could be considered across multiple levels. First, there’s the obvious nature of the aesthetics — does a renovation entail an authentic look, or the man-made sandscapes a la No. 7’s classic visage? Already, I can see sides being formed between the modern era’s biggest architects, debating what’s right and what’s best. And that’s just the iconic seaside holes! One of the most repeated critiques in all course analysis is the perceived value between those holes and the inland allotment. Does a renovating architect agree? And if so, do they stop at a proper restoration, or offer contemporary suggestions for the aim of improving what is already perceived to be an American top-ten course?

All this is to say that any restoration effort invites a litany of questions, not just at Pebble Beach, but at any of the courses we’ve discussed. Differing opinions on the answers to these questions suggest that it’s tough to be “finished.” For example, Brookside Country Club in Ohio is beloved of Ohio golfers, many of whom I know enjoy this Brian Silva restoration of a Donald Ross classic even more than they enjoy the more acclaimed Inverness and Scioto. Increased attention has helped it crack GOLF magazine’s U.S. Top 100 for the first time. And yet the club has recently hired Tyler Rae to create a master plan.

I certainly don’t have all the answers to these questions (except in the case of Bethpage Black, in which I pretend to). This exercise has left many questions open, namely the whats, whos, and hows. There is only one question that has been answered firmly by our panelists and their 255 nominations: Should it be restored?

The answer, it seems, is “yes.”