Last week, your correspondent took some liberties with word choice in the name of Twitter character count and, in the process, invoked rebuttals from two members of the online golf architectural community (two respectable members, whose opinions I value. Want to emphasize that moving forward).

My error, and one that makes quite the difference, was not being careful to refer to the tee shot at Wintonbury Hills’s No. 2 as “Cape-style,” instead implying (through poor syntax) the entire hole was a Cape. It is not in the least a “Cape” hole, and a quick Google search will make that obvious to you. My intended point, however, was to note the steep falloff on the left side of the fairway, which is where the proper angle to the green sits as well. A less gutsy player can hit to the wide right of the fairway, which offers a much tougher approach. The two response tweets were “Cape Holes have nothing to do with the tee shot” and “A true Cape hole only has the trouble at the end.” These comments came from gentlemen who know their stuff, and—again—I respect.

Both of their statements are 100% accurate. And I don’t agree with them.

Let’s start with the accuracy of their statement, because it’s important: Charles Blair Macdonald, the godfather of template golf, should probably get first say on what his own designs mean. And one of my opposition wisely quoted him accordingly: “The fourteenth hole at the National Golf Links is called the Cape Hole, because the green extends into the sea with which it is surrounded upon three sides.”

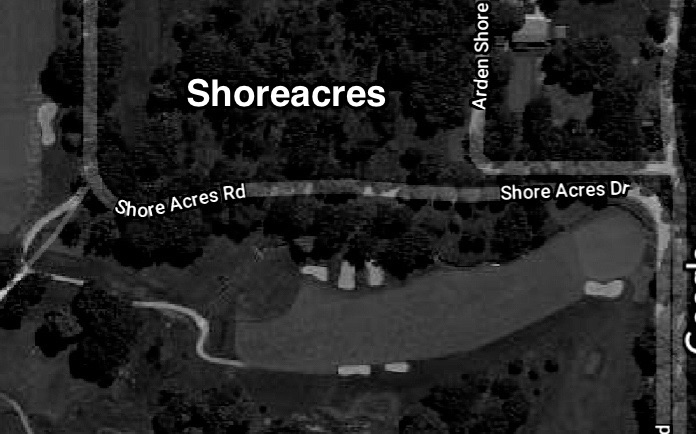

Indeed, the original “Cape” and many of Macdonald’s following entries fit this description. His Mid-Ocean, another classic Cape, features a green closely surrounded by three out-of-bounds areas. When three-sides-worth of water wasn’t available, Macdonald and his acolyte Seth Raynor lessened the penal nature and settled with bunkers; The Chicago Golf Club and Shoreacres include two wonderful holes to illustrate the point.

There is, furthermore, no note of Macdonald or Raynor making any claim regarding the tee shot’s standards of compliance in a Cape template.

As someone with a journalism background, I fully understand the frustration that comes with total amateurs contradicting weeks, or even years of expertise, with their dumb opinion (I am so tired of your dumb opinion that Deafheaven isn’t a trve black metal band). I can understand why someone dedicated to Macdonald’s work or Raynor’s work (the article linked above comes from Anthony Pioppi, perhaps the greatest living resource on Raynor’s work) would grind their teeth every year during The Player’s when analysts and players discuss the No. 18 “Cape.” The short and cruel truth is that Macdonald’s written intentions—calling for a challenging, precise approach—have been replaced erroneously with the belief that a Cape is defined by a how-much-do-you-dare tee shot, rewarding the most aggressive cut across a watery hazard.

The purists are not wrong. Certainly not at a technical level. But I might suggest another document and the power of interpretation, and why purist “correctness” is not as concrete as they claim.

Although the whole process seems to have shifted in the past decade-plus, the Supreme Court of the United States is not made up of Democrats and Republicans, but textualists and pragmatists. The Second Amendment is, and always has been, an ideal method of looking at this divergence of thought. A textualist would consider the intent of the founders and argue that the intention behind the Second Amendment was that citizens could and should bear arms, in the event that their government became tyrannical (as the founders themselves had just witnessed)—therefore placing limits on access to these weapons was in opposition to the intent of the founders. A pragmatist would argue that the Constitution was intended to bend with the times it currently represented, and that the fathers couldn’t have contemplated a firearm capable of killing 60 individuals before the assailant was stopped, therefore restrictions should be placed on access to semi and fully automatic weapons.

(Obvious aside: There is no implied correlation between your thoughts on template holes and guns. Just an anecdote.)

So let’s apply this to the constitution of template design. A textualist considers Macdonald’s written intent and makes decisions accordingly. Pete Dye’s so-called Cape does not fit the bill, as it’s hazarded on two sides, at best. A pragmatist considers how changes to our understanding of golf course architecture consequently results in a changing to the very definition of a “Cape.” It’s important to note, however, that this does not equate to wholesale elimination of Macdonald’s demands.

A Cape’s green must have the three hazards and this origin must be respected, even in adaptation. I will acknowledge that during the writing of this post, I reconsidered my own opinion and removed the “Cape” status from No. 18 at TPC Sawgrass. Never before had the bare right side of its green stood out so blatantly to me. That said, as a young progressive dude, I maintain that placing equal value on the tee shot as the approach (in short, a Par 4 requiring two precise, measured shots for a birdie chance) is essential to the nature of the Cape circa 2020. Therefore, in Sawgrass’s place, I propose No. 13 at Dye’s Kiawah Ocean Course…the same frightening tee shot, into a green well-defended at left, right and back. It is far from what Macdonald imagined, I imagine, but I would hold that it holds its own within the definition of a Cape.

This viewpoint, despite Macdonald’s words, has at least partial backing in the most simple form of pragmatic theory: “Do as I do, not as I say.” All of the aforementioned MacRaynor Capes demand a pure tee shot to ensure success.

Mid-Ocean’s photogenic Cape surrounds a lagoon in the same sense that the Dye Sawgrass installation does (with the necessary surrounding hazards, however). That’s an easy one. Water, water isn’t everywhere, however. At Shoreacres, the creek that ultimately wraps around the green should never be in play off the tee, but reaching the better angle at the left means carrying a sunken rough area (relatively easy) and challenging three bunkers as the fairway veers (more difficult). Chicago features a diagonal gash the cuts from far-left to near-right; although a far-right tee shot may have a better angle than far left, it also means contending with a fairway bunker that muddles the approacher’s view. Yale’s example is a little different, in that precision is everything from the tee (excluding a risk factor): going left or right of the hogsbacked fairway means a problematic approach. Even NGLA originally featured a creek up the right side, and a fairway that kicked left-to-right, challenging players to find the correct spot lest they end up wet after a run.

There are surely examples that live up to Macdonald’s definition in the strictest sense. If you still don’t buy in, consider the meaning of the template “Maiden” and how unlike the original “Maiden” Raynor’s rendition became.

Originating at Royal St. George’s No. 6, the name “Maiden” referred to a large dune players were forced to hit over, prior to the shifting of tee boxes for safety purposes. Macdonald’s “Maiden” refers to the hole’s green…not the title landform. That green plays more like a subtle Biarritz, front-to-back. Raynor (more often a Maiden user than Macdonald) turned the green sideways, and added an even portion at the front so the green was segmented with two higher platforms are back left and back right…similar to a Double Plateau (albeit not in the same pattern as a Double Plateau). Finally, most modern Maidens are Par 4s. The hole is very distinguishable from its inspiration…and yet we don’t seem to mind (read Golf‘s recent writeup for a less garbled explanation).

If you haven’t bought my malarkey yet, I’ll make one last-ditch effort using Tom Doak and Jim Urbina’s Old Macdonald. As the tour presented at Bandon’s website notes “an important distinction to make is, the holes are interpretations not replicas.” This is the necessary attitude for architects who understandably wish to further Macdonald’s exploration of ideal holes, while working with the land to create the most natural holes possible. Nearly all of Old Macdonald’s holes stem from a Macdonald design, and some are tweaked enough that I would argue they violate the necessary core of Macdonald’s intentions.

But that’s what I’m saying in 2020. Perhaps Doak and Urbina’s interpretations will eventually gather enough acclaim and replication to redefine their inspiration 40 years from now (I am especially keen on its Hogsback-inspired No. 4). I’m a relative young gun, maybe lacking the wisdom to fall in line with the definitions set before me.

Ask me in 40 years how I feel.