“I have known Charley Macdonald since the earliest days of golf in this country and for many years we have been rival course architects, and I really mean rivals for in many instances we widely disagreed. Our matter of designing courses never reconciled. I stubbornly insisted on following natural suggestions of terrain, creating new types of holes as suggested by Nature, even when resorting to artificial methods of construction. Charley, equally convinced that working strictly to models was best, turned out some famous courses. Throughout the years we argued good-naturedly about it.”

If you were to take A.W. Tillinghast’s word for it, the Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture was broken into two camps: those using templates, and those going without. There’s a kernel of truth to this…and plenty untrue as well. Tillie, for all his hay about the “natural suggestions of terrain,” frequently turned to templates. Tillinghast went as far as developing his own portfolio of templates. There are four, and this series will shed some light on these “lesser templates,” typically ignored in today’s conversations on the subject of designed holes.

The first has not actually been ignored at all, if we’re being honest. In fact, it’s quite popular. The Great Hazard is a rarity…a recognized Tillie template.

THE BIG IDEA

The hazard is big, and it’s also the big idea behind Tillinghast’s most famous hole concept. Do you ever golf with your father-in-law, or someone else who gets spooked by a pond that carries for 30 yards beyond the tee, and hits it in the water despite hitting driver? That’s the mindset you’re starting with on a Great Hazard hole. There’s no chance of hitting the hazard from the tee, but the specter of the second shot spooks. If you don’t find the fairway on the first, your ability to cross the Great Hazard during your second shot disappears (just like your chances at par).

These began as true three-shot Par 5s, and later evolved to allow risk/reward. A score requires an accurate tee shot, a second over the Great Hazard itself (which varies in length…that second shot can be quite long as well). Approach and putt(s). Find the rough on your first shot, and you’re taking three to get over the Hazard, and managing a next-level approach to find par.

THE ORIGINAL

There are two worthwhile theories here, and we’ll start with the more popular one: George Crump had money to burn at his Pine Valley project (at least when he began) and he had ears for a number of now-legendary Philadelphia architects: George Thomas, William Flynn, Hugh Wilson, and of course Tillie. The latter had the most outsized personality, and found in Crump a body to execute his greatest (pun) idea. The result was “Hell’s Half Acre,” an 160-yard carry of sand and scrub, the central feature to No. 7 at Pine Valley. You’ll probably recognize similar images of the above hazard, but the original was far more intense, as Crump created legitimate dunes climbing from one fairway to the next. If that wasn’t grotesque enough, there’s a second forced carry required to reach the green (and also a sandy expanse from tee-to-fairway…but again, this shouldn’t be a hazard for folks who aren’t my father-in-law).

Now here’s an interesting twist. What if Tillinghast didn’t actually originate the Great Hazard idea? What if…it was… his nemesis* Charley Macdonald?!?*

* = emphasis ours.

No. 9 at National Golf Links of America—the Smithsonian for template golf—is Macdonald’s take on “Long,” the biggest hole at St. Andrews Old Course. The inspiration for “Long,” and most of the MacRaynor variants to follow, feature a “Hell” bunker…rather large, if not titanic in the Tillinghast mold. At No. 9, Macdonald brought together a variety of sand hazards—a big ol’ bloc of sand…a collection of smaller bunkers…and even tossed a bunch of church pews at another point—stitched together with natural. Essentially, a “Great Hazard” five years prior to Pine Valley’s rendition.

It’s worth noting that the Great Hazard is realistically a one-up of the Long template, and the “Hell’s Half Acre” title may be a reference to the infamous Hell bunker at St. Andrews. Still, I’ll argue that Great sets itself apart for its relative audacity and the forced carry it requires.

Then again, it’s not like Scotland didn’t have its own huge hazards mid-Par 5. The Cardinal bunker at Prestwick’s No. 3 is the same story. Maybe that’s why it’s popularly now known as “Tillinghast’s Great Hazard” now…Tillie’s legions led an aggressive campaign to market the concept as such. Its universality may make it the least “owned” of Tillinghast’s templates, but perhaps also the best.

TWEAKS

We suggested that Crump’s obsession, and budget, had a hand in making Hell’s Half Acre the baddest of the bad. Perhaps Tillinghast’s future employers, while appreciating the concept, requested the headstrong sadist tone it down a tad…either for members’ enjoyment or for simple maintenance costs. The majority of Tillie’s Great Hazards coming thereafter were not huge expanses of sand—such as Pine Valley’s—but rather large clusters of bunkers that, when combined with the natural and scrub running between them, served the same purpose (i.e. at the Philadelphia Cricket Club). Some didn’t require sand at all; Ridgewood Country Club’s Championship course features two separate Great Hazard holes, and both feature no sand, relying only on mounding and thick rough. Those that do feature sand rarely reach the 160-yard length of Hell’s Half Acre.

The general strategy behind a Great Hazard is less nuanced than the greatest of Macdonald’s multi-shot templates. Hit a good tee shot, and then cross hazard…or don’t. Tillinghast improved the idea with time, to add more strategic initiative. One logical option was to extend an arm of the second section of fairway into the hazard and provide an easier reach. This location allows a less friendly final angle to the green, however, whereas those biting off more of the Great Hazard would be rewarded with a better (and usually shorter) look.

An especially interesting Great is the famous No. 4 at Bethpage Black, where strategic choices are required from both tee and approach. From the tee, those looking to get home in two will almost assuredly need to carry a sizable fairway bunker to have even a clear look at the bunker cluster that fronts the green. If they get second thoughts (most will), they’ll have a clear sightline to the second fairway, which angles toward the right. Those who take the safe route from the tee won’t have it so easy during their second shot: The infamous “Glacier bunker” that serves as the Great Hazard angles from back right to front left, and the height of the hazard also decreases as it moves forward. Therefore those who take a risk from the tee get visibility as a reward, while the more conservative must hit blind over the mammoth hazard (an especially unfriendly task considering the current Rees Jones-thin fairways).

MODERN TAKES

I haven’t done a ton of research on this, but it’s reasonable to suppose modern architects don’t aim to replicate the Great Hazard as much as they do a template such as the Redan. That much sand costs money to maintain. At least one great Great example has emerged at a new course very much in the spotlight, however, and for the life of me I can’t figure out why no one has used the “Great” terminology on it yet.

No. 9 at the newly remodeled Pinehurst No. 4 is a heck of a Great Hazard template hole. A short Par 5 (527 from the tips), the choices made here will often be the difference between birdie, par, or worse. The second area of fairway is angled so that the leftmost point is maybe 80 yards nearer to the player than the rightmost. The rightmost point, of course, offers the best angle to a green that’s stabbed from the left by a bunker.

Hanse has a bit more of a wild streak in him than most, so not surprising to me he’d go a little nuts and make a 21st-Century kaiju bunker. Update: Hanse has 100% said this hazard was based on Hell’s Half Acre.

NOT GREAT HAZARDS

The most obvious case of “not Great Hazard” is a large stretch of mess right off of the tee box. If that were the case, Pine Valley would have something like half a dozen Great Hazards. No; although a Great Hazard is a great addition to any course playing to the “heroic school” of golf course architecture, it’s not a “Great Hazard” if you use a tee to hit over it.

Another no-go is any hole where you can go around the Great Hazard, regardless of how tricky that trip may be. For example, there are numerous Par 5s at Tobacco Road where one may opt to make a massive sand carry and theoretically reach the green in two. But there are also long ways home for those of us with less muscle. Not a “Great Hazard,” no matter how big that hazard is. This applies to some Tillinghast courses as well. No. 3 at Fenway Golf Club (another Westchester County course from Tillie) has a very large, very attractive bunker complex jutting into the fairway from the right. There’s more than enough fairway to work with to its left, however.

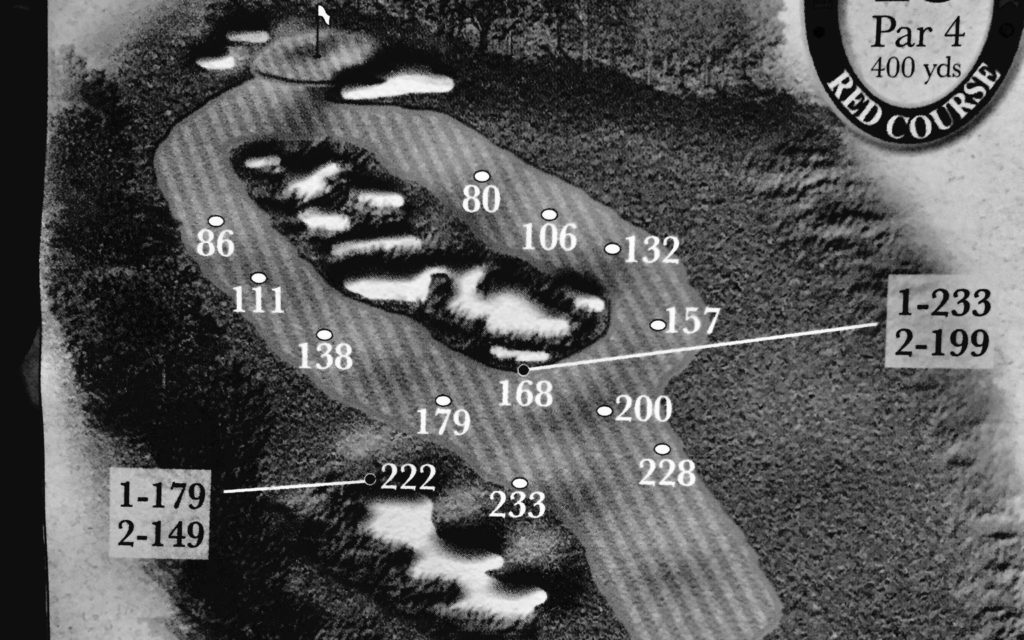

One last Tillinghast non-Great comes from Bethpage Red, Black’s “little” brother. Many like to refer to the centerline hazard at the Par 4 No. 13 as a “Great Hazard,” but no dice. It’s huge, stretching for 125 yards down the middle of the fairway but “laying up” isn’t intended as a viable strategy. You simply choose to go left or go right (always go left…it’s easier and offers the better angle). It’s the eye-catcher at Red, but also one of its weakest from a strategic perspective.

Come back next time when we’ll discuss a more controversial Tillinghast template…the “Double Dogleg.”