The Masters stars tomorrow, and we feel inclined to wade into the vast content swamp that is Augusta National. Our pitch for your slavish attention: Eisenhower Tree, and did it make any difference at all?

Eisenhower (a loblolly pine) stood above among the many landmarks at Augusta National. And, as we’ve established before, we love a good, iconic golf tree. Everyone knows the story of how then-President Ike wanted it gone, and how Augusta’s board stood its ground. Everyone loves the story so much that we still hear it at least once on every Masters broadcast, even after the tree met its end at the wintry hands of an ice storm during 2014. It’s kinda the only thing they can talk about, outside of Jack Nicklaus’s iconic birdie putt in 1986.

We, being stats-based folks, wanted to take a look at the limited numbers we had access to and judge just how much the tree actually impacted play during The Masters by looking at 2014 through the present (it came down in February of ’14) compared to its glorious past.

Here’s what we found:

It didn’t make any difference.

ESPN’s hole stats only go back to 2011, so these numbers are hardly definitive. But just for argument’s sake: During the five-year stretch after Eisenhower came down, “Nandina” has played as the no. 7 toughest hole at The Masters (6.8 average), while playing as the eighth-toughest hole prior. With limited statistics, that seems to imply the loss of the tree actually made the hole a touch more difficult. Let’s keep going.

The scores recorded during both spans are equally equivalent, but still give a slight nod to post-Eisenhower as the tougher hole. Within the small sample size, Nandina is actually giving up fewer birdies (avg. 23.5 after vs. 30 before), fewer pars (192 vs. 197), and costing more bogeys (73 vs 69) than it was previously. We can feel Nate Silver shaking his head so we’ll go ahead and say it: The slight difference in these two ranges are basically irrelevant among the roughly 280 rounds played at The Masters every year.

But still, it’s at least fair to say the loss of the Eisenhower Tree has made no difference to the challenge of Nandina.

Here’s where most people go wrong in interpreting the data, however. The easiest argument to make—anywhere, but especially Augusta—is that technology has rendered portions of Mackenzie’s work obsolete. Eisenhower stands a mere 210 yards from the teebox; can’t most pros get over that? The same truth has widely applied to No. 10 Camellia’s fairway bunker since 1937.

Stats say otherwise, however. Not that Eisenhower is still a valiant foe, but rather that it was never actually a momentous foe. Consider Nicklaus’s last Major victory, the aforementioned ‘86 Masters. With the “limited” technology, theoretically, Nandina should have really screwed folks up. And yet, 15% of the field came away with birdie during the 1986 tournament when playing No. 17. That’s about 42 total birdies…whereas the hole has averaged an 8% scoring rate from ‘14-’18. The same applies to bogeys. About 18% of the field lost a stroke in 1986. Compare that to 26% over the last five Eisenhower-less years.

We may be downplaying the tree’s significance, but we acknowledge there is no way the removal of a massive pine from the left of a hole’s fairway would make any hole tougher in the long run. By itself.

The answer certainly lies in the trees, just not this one.

Nandina has, yes, also gotten longer. Between updates during 1999 and 2006, the hole has increased from 400 to 440 yards. Notable, but not notable enough. It’s the other ‘00s overhaul that made the ultimate difference.

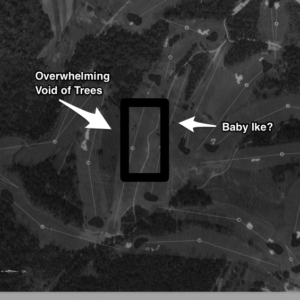

That’s when the tree island appeared. Located between the No. 15 and 17 fairways, this 150-yard strip took a classic Mackenzie choices-choices-choices hole and made it a do-or-die. Although Eisenhower hogged the attention, Nandina’s intended weapon has always been its final destination, one of the toughest greens on a course full of them, and an even tougher approach shot. Golfers aim to approach from the highest point on the fairway (on the right), so they can avoid an otherwise blind shot from the bottom of the slope (on the left). Taking the “Eisenhower line” gets you closest, but consequently the worst look at the green. Take it to the right and get the only manageable view of the green. Too far right, hit the tree island.

Back in the day, golfers would hit almost far enough right to meet the No. 15 fairway, in their attempts to approach Nandina’s green from a better angle. The addition of rough at Augusta ruffled many feathers, but the trees truly made No. 17 a killer. Golfers who played toward Fire Thorn to come hot into Nandina—such as Nicklaus during ‘86—were now left a much smaller (and left-er) target. In short, Nicklaus’s approach wouldn’t even be possible today.

Augusta was borne of a St. Andrews-inspiration: The best golfers could win by playing the perfect line. Skilled golfers could also win, however, by making great plays from alternate routes. Now Nandina is strictly “the perfect line” or die.

Getting back to the question you expected to be answered: What does this mean for Eisenhower’s legacy?

Nothing good. It would be one thing if Rory McIlroy could get over it in a risk-reward bid for a better angle. But he wouldn’t try; getting over the loblolly meant a worse view than playing to the top of the fairway. So while Eisenhower may have gotten stuck in the tree a dozen times, it’s not necessarily because he meant to hit in that direction.

Bernard Langer has played in a few of these, and he says:

“The Eisenhower Tree was very special, but the hole is a better hole without the tree. And they have done statistics where it was mostly the members who hit the tree. In the tournament, very few would actually hit the tree.”

There’s something to be said about visual intimidation and architectural strategy, and indeed, we wrote as much about the aforementioned “Rory’s Oak” at Kiawah’s Ocean Course (also RIP). That live oak intimidated players into going long and right, which in turn offered the toughest approach (wiser players knew laying up short and approaching over the oak was the best play). Eisenhower pushed golfers to aim long and right…which also led to the easiest approach. It was a scary feature that offered no real reward for challenging it.

That’s probably why “Rory’s Oak” has been replaced, and Eisenhower won’t be. It’s an icon, like Andrew Jackson.

But we’re probably better off without him.