I’ve been attempting to catch up on golf literature and my wife assisted this Christmas with a copy of Golf Has Never Failed Me, a compilation of Donald Ross’s scant writings, organized to provide insight into the Scot’s approach to golf course design.

It won’t provide many mind-boggling realizations for those who have a generalized understanding of Ross’s rather generalized style. Simply the bare necessities for planning a golf course (from finding a property to draining it) and the strategy of laying it out (from routing to Ross’s range of sand hazards).

There was one subject that intrigued me, however, which Ross put far more emphasis on than the average 2020 GCA conversant:

Tees.

“The old courses in England had separate tees at every hole. The old courses had tees so long and wide that you never knew what kind of shot you were going to have at any given hole,” he wrote. “The modern golf course should either have tees fifty yards long or three or four separate tees at every hole.”

That’s a lot of tee…a lot more than you see at the average golf club during 2020. So I got to thinking…what holes would benefit from the application of this Ross principle? The possibilities were endless, but I’ve narrowed it down.

Many are tweeting their “best golf courses I played for the first time during 2020” lists. So I decided to jump onboard the rubbing-it-in train, while also creating some worthwhile conceptual content (hopefully).

So here are the six best courses I played for the first time during 2020 (not in order), with emphasis on how they currently practice Ross’s teachings or, more likely, my radical reinterpretation of one of that course’s tees to change the hole’s play.

So let’s start with two courses that are doing it correctly, at least part of the time.

Ross noted two primary reasons for long tee boxes: One, he understood members at championship courses would need different distances to match their abilities. But more importantly, he understood different conditions would lead the hole to play in different ways on a day-to-day basis. This was certainly true in the UK, where winds can alter an approach by a range of six clubs or more. It was especially true for the inland, clay-based courses of the United States, where a few days of rain or a few weeks without would alter the bounce of the turf. Thus Ross encouraged superintendents to move the tees toward the front of that long tee box for wet conditions, or when facing a stiff wind. And, accordingly, move them back when baked soil would add additional yardage to a drive.

Bandon Dunes features ideal, links-like soil, so those clay-based concerns don’t bear much weight. It absolutely faces seasonal winds, however.

Look at a yardage book from the resort; along with a map of the routing, the typical Summer and Winter season winds are noted as well. The speed of the wind is hardly guaranteed, but its presence most assuredly is. And so we arrive at Pacific Dunes, certainly the best course I played for the first time this year.

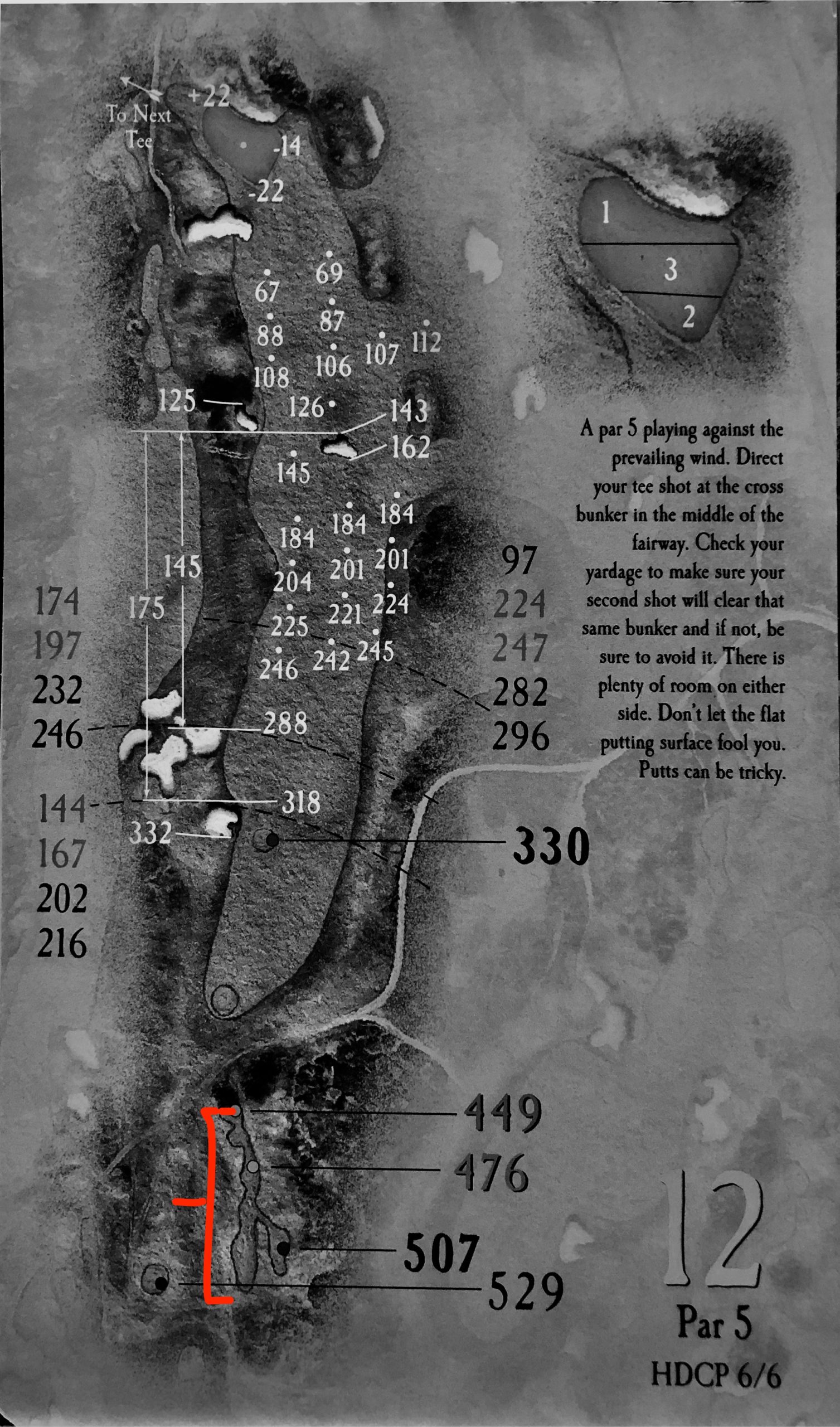

Consider No. 12, a 529-yard par five playing north parallel to the coast. Its primary tee box is 80 yards long. One one hand, this allows it to host three sets of tees on an average day…but it also allows management to lengthen and shorten the hole based on conditions. For example, the tees could be placed to shorten the hole during the Summer (where the “Summer Prevail” will blow south into the player’s face) and lengthened in the Winter (when the average wind will blow north behind the player and toward the west).

I say “could” because I don’t know if this was the strategy in this, and numerous other tees at Pacific’s design. If it were, it would be a great example of Ross’s design elements in action.

He also recommended big tee boxes for altering the day-to-day strategy of holes, however, especially par threes. Pete Dye, a noted Ross fan, copped the concept at Pete Dye Golf Club.

No. 7 is most noted for its reveal to players, who see it when emerging from the Pinnickinnick Mine. The tees are arranged at different altitudes, heading up the mountain slope, but the relevant one here is the lowest…a horseshoe-shaped stretch of turf that lines the mine tunnel from which the players emerge. It’s more than just a showpiece, however. The tees can be moved around the horseshoe; this only slightly alters the yardage of the hole, but more importantly, it alters the angle to the green. Tees to the left have a more straight pass into this green, which moves from front left to back right. Tees shifted to the right mean players must contend more with tree long, deep bunkers (and native) that line the right side.

This won’t necessarily match the challenge of the longer tees, but pushing the back tees up to this lower level does force the player to change club from the day before, a challenge more uncertain because the change in altitude from the back tee to the front is perhaps 30 feet.

Ross did this more dramatically on occasion, creating entirely separate tee boxes to shift the approach to a par three from day-to-day. It’s no different than how Pacific Dunes’s No. 9 plays from the same tee to separate greens from day-to-day. He cites a short at Gulf Stream Golf Club specifically during Golf Has Never Failed Me.

Alright, so now that we understand the reasons why Ross wants to supersize our tees, let’s look at some examples of how he (and more relevantly, I) would spice up the tee game at certain holes at the cool courses I played this year (ordered from least to most extreme).

Bandon Trails, No. 9

Bandon Trails was the toughest option because of its forested surrounds. Although the fairways are plenty wide for a solid golf course, we’re loathe to suggest tearing down trees just to widen a tee box. And, in the cases of holes that run next to each other, you can’t lengthen or angle a tee box into another hole’s fairway. You know, safety.

Finally, most of the par threes on this route are designed to do what they do; adding a separate tee for a subpar way of playing the hole isn’t what we’re here for.

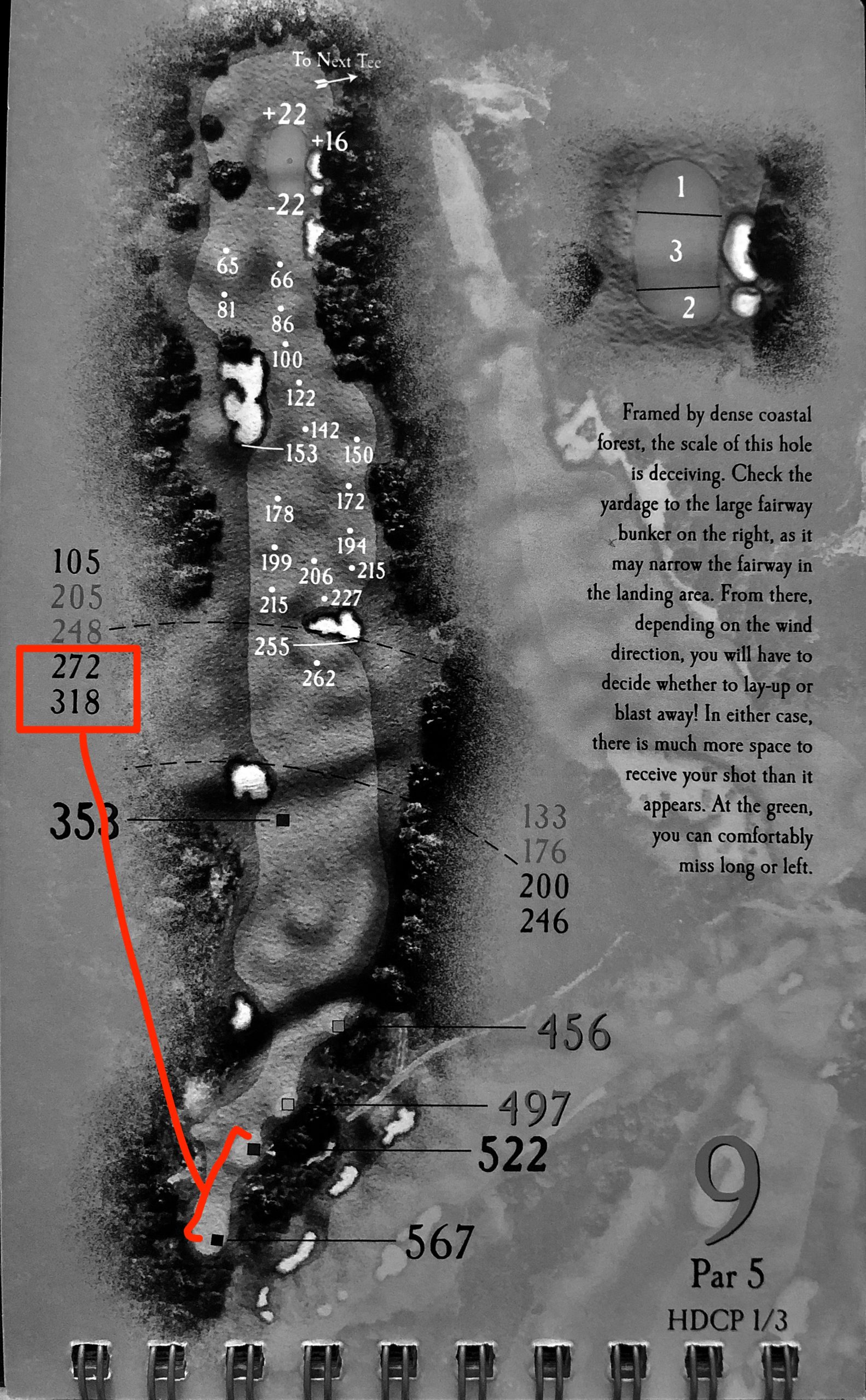

So at Trails’ No. 9 hole, we’re taking a somewhat straightforward approach to how changing distance from the tee impacts the player’s approach that day. According to the yardage book, the distance to the right fairway bunker is 318 yards…not reachable for most on this, a 567-yard hole. If the tees could be brought up 45 yards, now players are considering whether they can clear the bunker — now 273 yards away — or whether they should lay up (and the bounce of this linksland turf will add to these concerns). There’s a tight fairway slot left for risky runners, but this increases the likelihood the second shot will be contested by the imposing pine of the left side of the fairway.

No. 9 wasn’t designed to be a two-shot hole but events like the U.S. Amateur, where multiple rounds could be played at Trails, makes shortening it an enticing possibility. And, similar to Pacific, the seasonal winds make a difference. The Summer Prevail at players’ backs may have them tempted to cross that cross bunker if the tees are nudged up a few yards.

Erin Hills, No. 15

You know what’s more fun and way less subtle than making a par five potentially reachable in two? Making a par four drivable.

Granted, Erin Hills totally took a stab at this during the 2017 U.S. Open. It was a good idea, with mixed results. Saturday’s pin position was at the upper-left of the green, more accessible from the tee…which had also been bumped up to 288 yards. It wasn’t necessarily an eyrie, but the it gave up three eagles and 31 birdies, playing nearly half a stroke under par; No. 15 played as the easiest hole of the tournament on Saturday.

Which makes it all the more interesting that it played as the tournament’s toughest hole on Sunday, adding exactly a stroke on average from the day before, despite only playing 370 yards. This was the result of placing the tee on the far right side of the green, divided from the back-left by a significant ridge. The results were brutal as players tried to land, and hold, the far side of the green without tumbling back down.

So why not combine these ideas? Take the 290-yard tee option and place the flag over the ridge. The majority of PGA players will be able to reach the green, but a can they get close to the target? Scads of three-putts and roll-offs will return will better realize Sunday’s risks and Saturday’s rewards as a strategic golf hole.

OK, so that ended up being less of a chat on how to enlarge the tee box, and more about how to execute once you’ve done it. Sorry.

Blue Mound Country Club, No. 17

Alright, let’s have a bit more fun. During the same trip as Erin Hills, I had the chance to play a very different form of golf at Blue Mound, a showcase of Seth Raynor templates (with some fine standalone concepts as well). I knew, for the purpose of this post, that I would need to do at least one par three and that par three needed to be at Blue Mound.

Why? Because MacRaynor templates come with pre-packaged strategy. That’s not a knock (at least from my perspective), as the properties frequently alter the appearance and facets of the hole. But still: If you know the strategy for a Redan, you know the strategy for a Redan. The challenge was to choose a short hole at Blue Mound and find a valid alternative for playing it (and hopefully ruffling some MacRaynor feathers in the process).

So which to choose? The Redan and Biarritz were immediately disqualified…these holes literally don’t work from alternative angles. The Short was an option, but the current perched tee is significantly better than alternative ideas, plus a green that’s entirely surrounded by bunkers is entirely surrounded by bunkers at any angle.

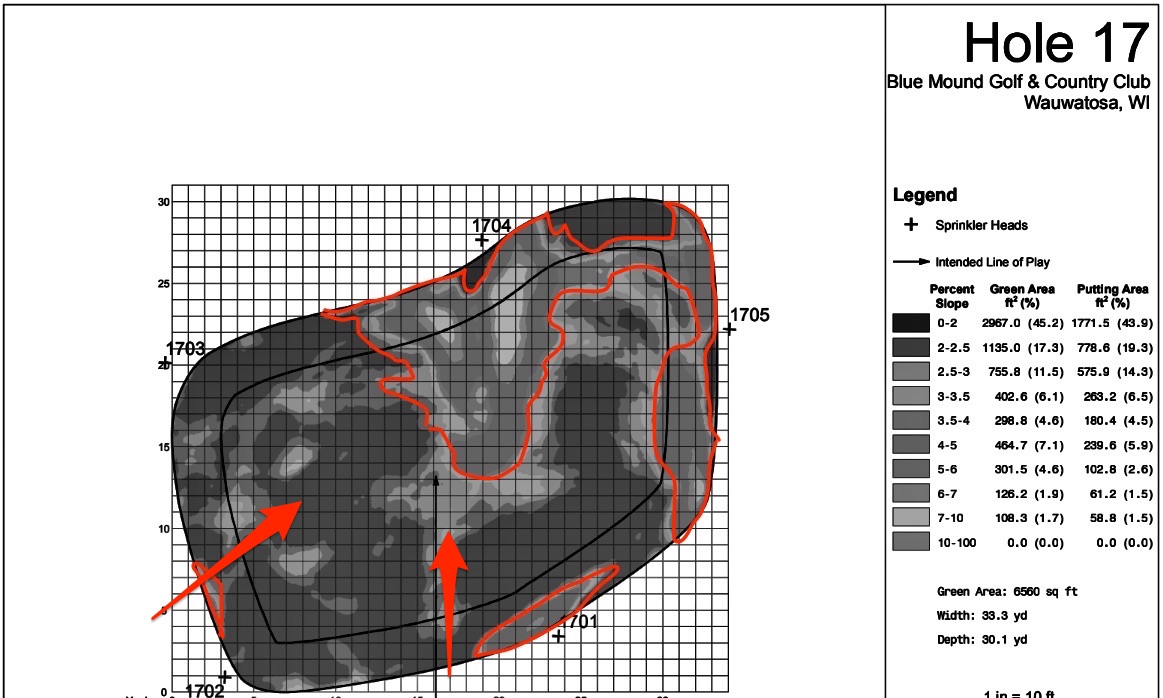

The only remaining option was the Eden, which I acknowledge was my least-favorite par three at Blue Mound anyway.

My most shallow beef is the bunkering; I’m a big believer in the Eden template having the respective Shelly, Hill, Strath, and Eden hazards. Blue Mound has an obvious Hill and Eden (at the left and back) but its front right hazard is a sort of hybrid Shelly/Strath, which leaves the front of the green a little open for my liking.

(Also, the original Eden doesn’t play head-on to the green, but that’s not the end of the world).

Anyway. That’s all water under the bridge over the Eden river. The point is that I don’t feel too bad about finding a new way to play this hole from day-to-day. And I take my inspiration directly from the aforementioned No. 9 at Gulf Stream Golf Club. There, Ross placed separate tee boxes to the left and right of the No. 8 green, creating drastically different approaches to the green. At Blue Mound, I’ll clear out the trees to the left of both the No. 16 and 17 greens, creating a hole of a slightly shorter length, across the property’s creek and forcing a carry of the Hill bunker to land on the putting the surface (unless you bail out to the existing fairway strip).

The severe swale that cuts down the middle of this green from the back will create an intense range of pin positions, which will place emphasis on finding the correct part of the green…just like some of the course’s other exciting greens, such as nos. 2, 6 and 10.

Inverness Club, Nos. 2, 11

What could be more interesting than making revisions, based on Ross’s preaching, to one of Ross’s own courses?

His suggested rules on tees are the rules he broke most often. More often than not, it was simply a question of space. Wide fairways are ultimately more important than huge tee boxes, and wide fairways also mean it’s tougher to create wide, or angled tees, because they may get too close to danger.

The Inverness Club has a great opportunity to shift play using such angled tee boxes. First, Ross’s words on the benefits of such a construct:

“Don’t let your domineering tape-measure man insist it is essential that the tee be cut square to the line of play. Frequently there are locations where a diagonal tee is good, especially when it allows movement of the markers to give variation in the length of the hole.”

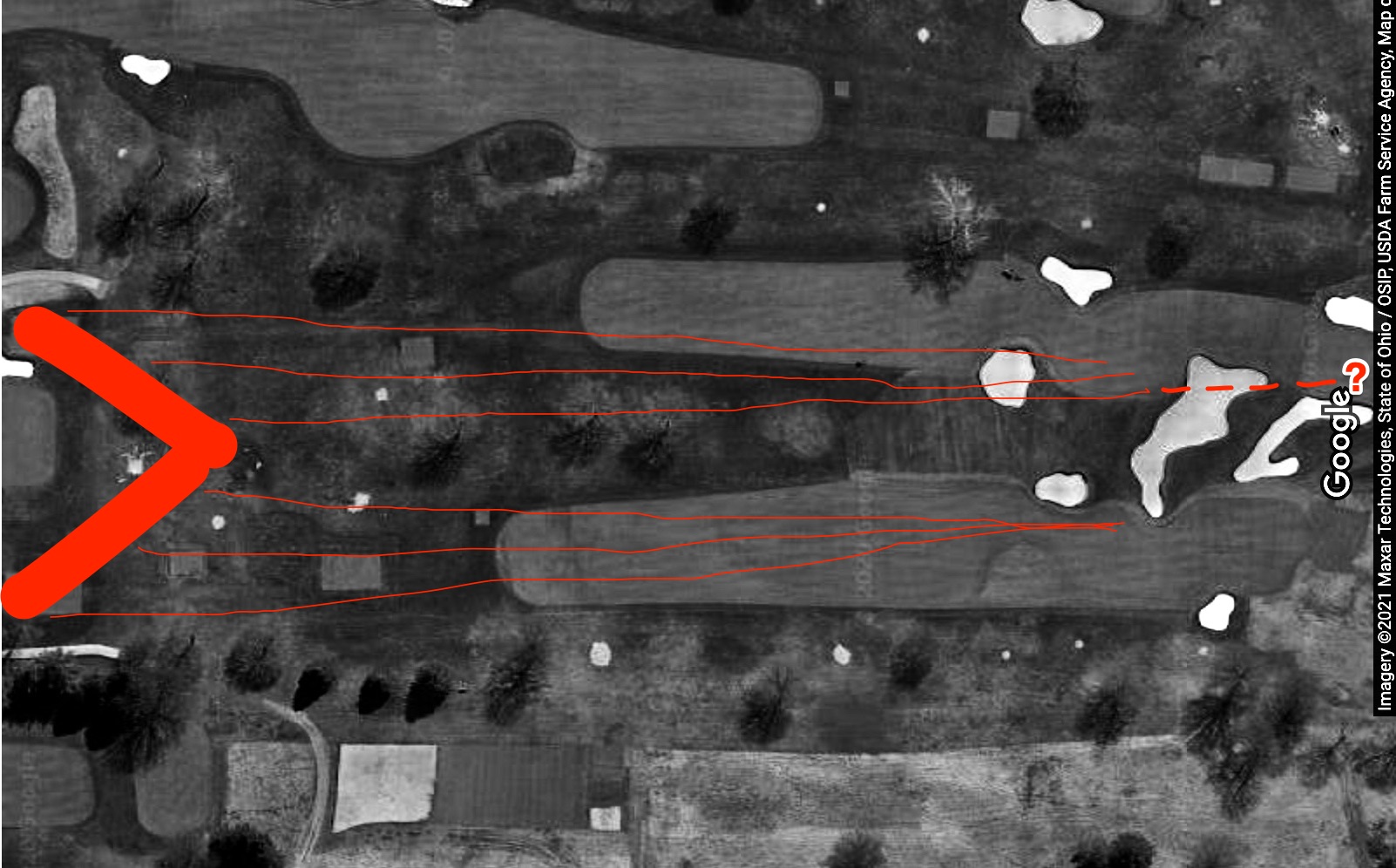

Our diversion is less to change the length of the hole, and more to change the play of the hole by adjusting the angle from the tee, and we can do that by combining the tee boxes from two holes.

It’s not unprecedented at Inverness; after all, the No. 1 and 10 tee boxes sit on the most famous example of Ross’s “forked fairways.” Why create a larger, shared tee at Nos. 2 and 11, respectively? Our vision is to create one 50-yard tee for each hole, with each beginning at the tees’ current end point. The No. 2 teebox will then stretch southeast at a 45-degree angle, and the No. 11 teebox will do the same, but heading southwest.

The result is a single, flying-v tee box. As with Dye’s horseshoe, there is method to the madness.

The pair share something in real life: two sizable sand hazards, which stretch from No. 2’s left side to No. 11’s right. On No. 2, playing your drive closer to the hazard results in a safer angle to the green. No. 11 is nearly 100 yards shorter, so the question from the tee is rather to lay up or try to land in the safe space between three large hazards.

Moving the former hole’s back tee toward the point is similar to moving the tee rightward at Pete Dye No. 7: It creates a more hazardous line toward the promised land by bringing bunkers more directly into play. Bringing the latter’s tee close to the point makes the risky, longer landing area that much more tempting. Theoretically, at a PGA event, this hole could measure as little as 330 yards, making it very tempting for the tiger. The closer one tries to hit to the green, of course, the more the potential mayhem.

Just thoughts, all of them.

Hoping that in a year from now I will have completed another essential piece of golf course reading, and will be ready to apply my ridiculous thoughts to an even juicier list of new courses played.