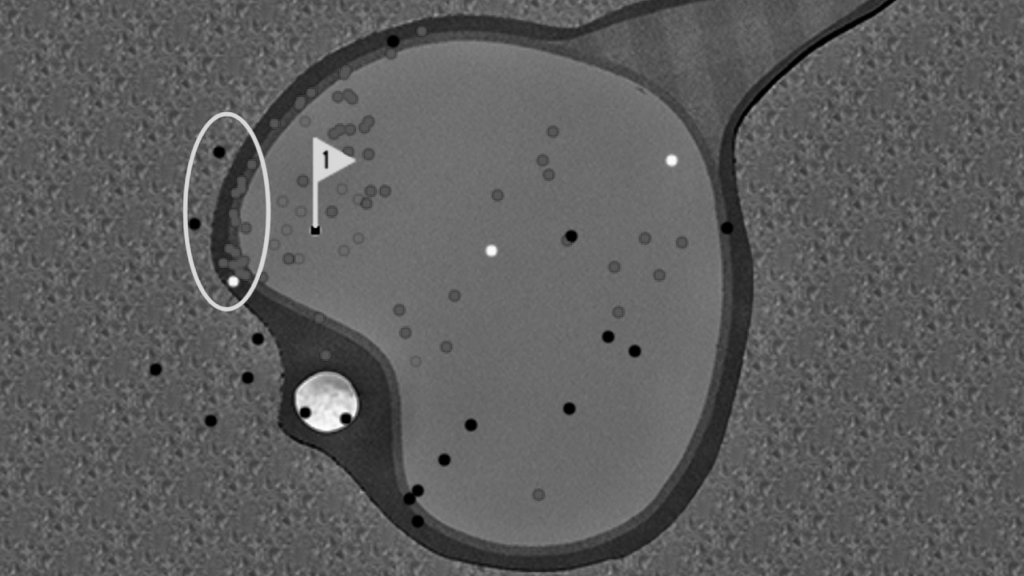

The Players Championship returns this week and I return to an eye-catching graphic that was shared by Garrett Morrison last year, displaying a dispersion of where tee shots had landed on the infamous island green, No. 17, for the day’s pin position, at the front-left. Six golfers, yes, had splashed down. More noticeable were the number of balls that “miraculously” came to rest on the edge of oblivion.

The reason is an inverse of a philosophy that I preach for golf design, albeit a rule that may seem counterintuitive to golfers, the majority of whom live in Western capitalist systems: Those who miss nearest should be punished dearest.

This rule largely doesn’t apply to most activities. If my son gets a 98 percent on his test, he doesn’t deserve a C if the individual with an 89% gets a B. The opposite logic to golf, based on Max Behr’s “line of charm” concept. Standing at the tee, a golfer who understands the tenets of risk-reward strategy knows that playing as near to the corner hazard as possible should result in the best approach angle. Those who air away from the hazard aren’t punished per se but they fail to reap any real reward.

But what about those who miss, like, bad? The high handicappers? Maybe they had a safe shot in mind. Maybe they had a risky one in mind. No matter where they aim, these golfers are statistically less likely to hit their mark. “Miss nearly, pay dearly” argues that these golfers shouldn’t be punished worse for missing bigger. In fact, courses should air on the side of mercy to keep pace of play moving along.

An island green is a bit of an exception (and doesn’t make much sense on a non-Tour course). Still, we can see in the aforementioned graphic how those who challenge a more intimidating pin end up suffering less than those who played it safe and landed in the center of the green. As can be expected, those who miss big get wet. Here, those who miss near end up okay. That’s because there’s a ring of second-cut serving as a backstop for hard-rolling spinners and cushioning soft bounces, essentially an insurance policy. There’s no real reason for players to take the conservative option; the PGA will protect them from the fallout of poor execution on their risk-taking.

The island green is admittedly a bad place to explain my “near miss” philosophy as it’s a fairly binary affair. “Miss nearly, punish dearly” is ultimately a rule that is intended to maintain playability at courses enjoyed by a wide range of handicappers. Let’s consider a poor example to see how the inverse application of my rule (however inadvertent) results in a poor strategic hole.

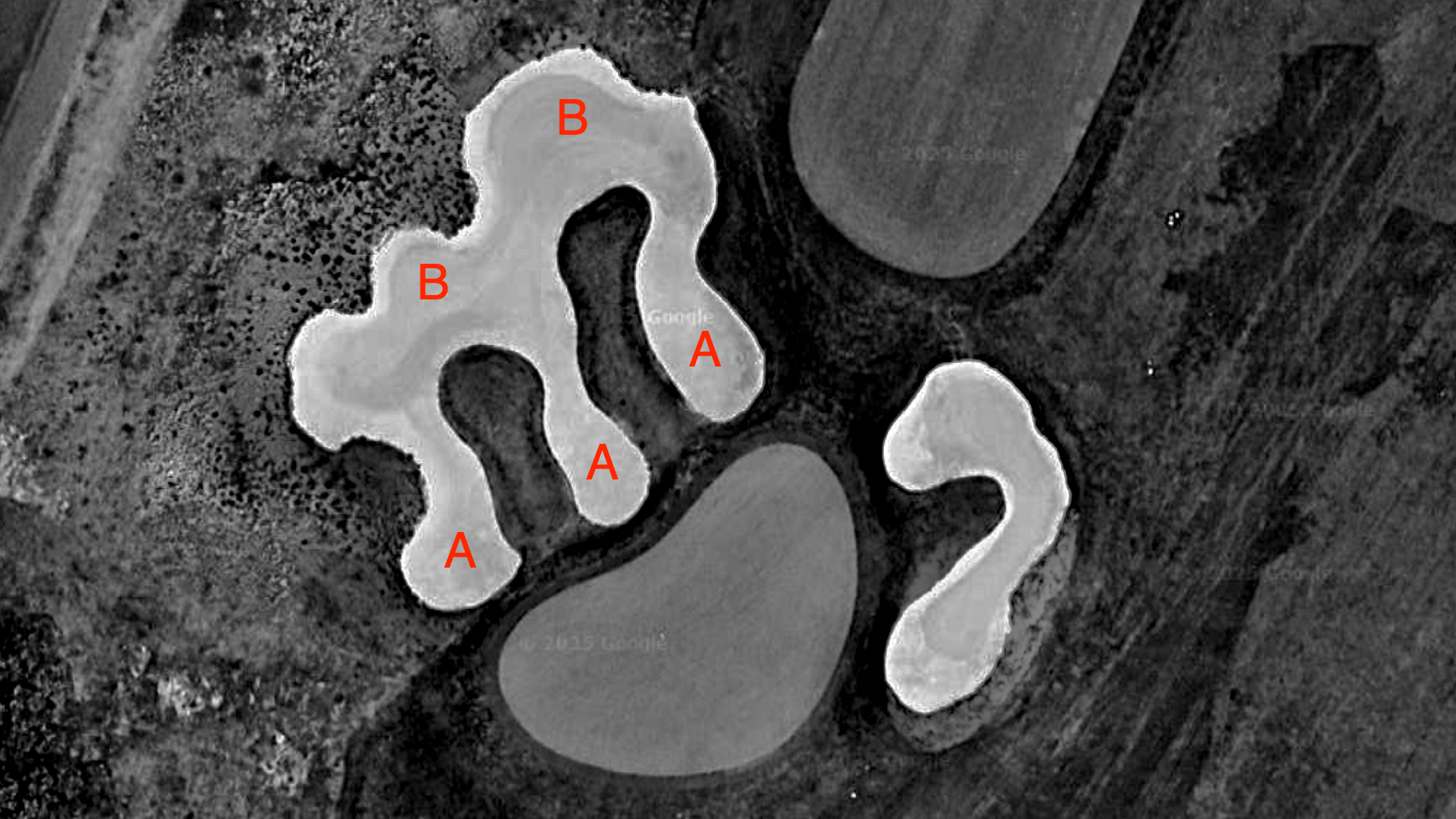

Below is No. 10 at Triggs Memorial, a Donald Ross municipal option in Providence. The current version features a bunker located approximately 15 yards to the right of the fairway. It’s reasonable to assume that a better golfer will miss this thin fairway by less than 15 yards…maybe 10 feet. To hit the bunker, one would need a classic duffer slice, the kind that comes more and more frequently as the handicap gets higher. At this point, my five-handicap friend (point A) is prevented from going for the green by the tree planted farther up but he can certainly hit a comfortable fade to land ahead of the centerline bunker. Meanwhile, 15-handicap me (point B) may need to play laterally to the fairway, as it seems unlikely that I can either get my ball high enough to clear the tree, or sting low enough from the sand to get under it. The result is that the lower-handicap player ends up with a 70-yard approach to reach the green in regulation and the higher handicapper has a 220-yard shot for the same result.

At left is the current state of No. 10 at Rhode Island’s most prominent public Ross. At right is roughly how Ross’s original hole stood, resulting in a hole both more strategic and more equitable, if I’m still allowed to say that without losing my federal funding. (Photo Cred: Google)

At left is the current state of No. 10 at Rhode Island’s most prominent public Ross. At right is roughly how Ross’s original hole stood, resulting in a hole both more strategic and more equitable, if I’m still allowed to say that without losing my federal funding. (Photo Cred: Google)

The lesser player ultimately deals with the more difficult shot because his miss, on average, is bigger, even though the better player is more equipped to handle such a challenge.

Let’s consider how flipping the formula would improve the hole in terms of both strategy and playability…because that’s exactly how Ross designed the hole.

Based on Ross’s drawings, the bunker on the right once sat flush with the fairway, prior to shrinkage and trees appearing. Landing near to it left you the best angle into this short par five; a bunker along the far left of the fairway inhibited long approaches. The best players, then, would aim for point A, and either thrive or suffer accordingly. And what about a hack like me? At this point, the expanded nature of the fairway has given me less reason to aim anywhere near the bunker. I can aim much farther left and, even if I miss, suffer less for it. Does it give me an unfair advantage over the lower handicapper? At my skill level, I’ve still got my work cut out, even if I’m not in a bunker.

That said, my hole hasn’t become a muni nightmare either, where the group behind is forced to wait while I hack-and-slash to a 10. Both a competitive balance and pace-of-play have been improved by Ross’s rendition.

(Note: If you need another reason why tree-lined fairways are poor design, or why active upkeep is important at the municipal level, you can add “because trees make the poor poorer”).

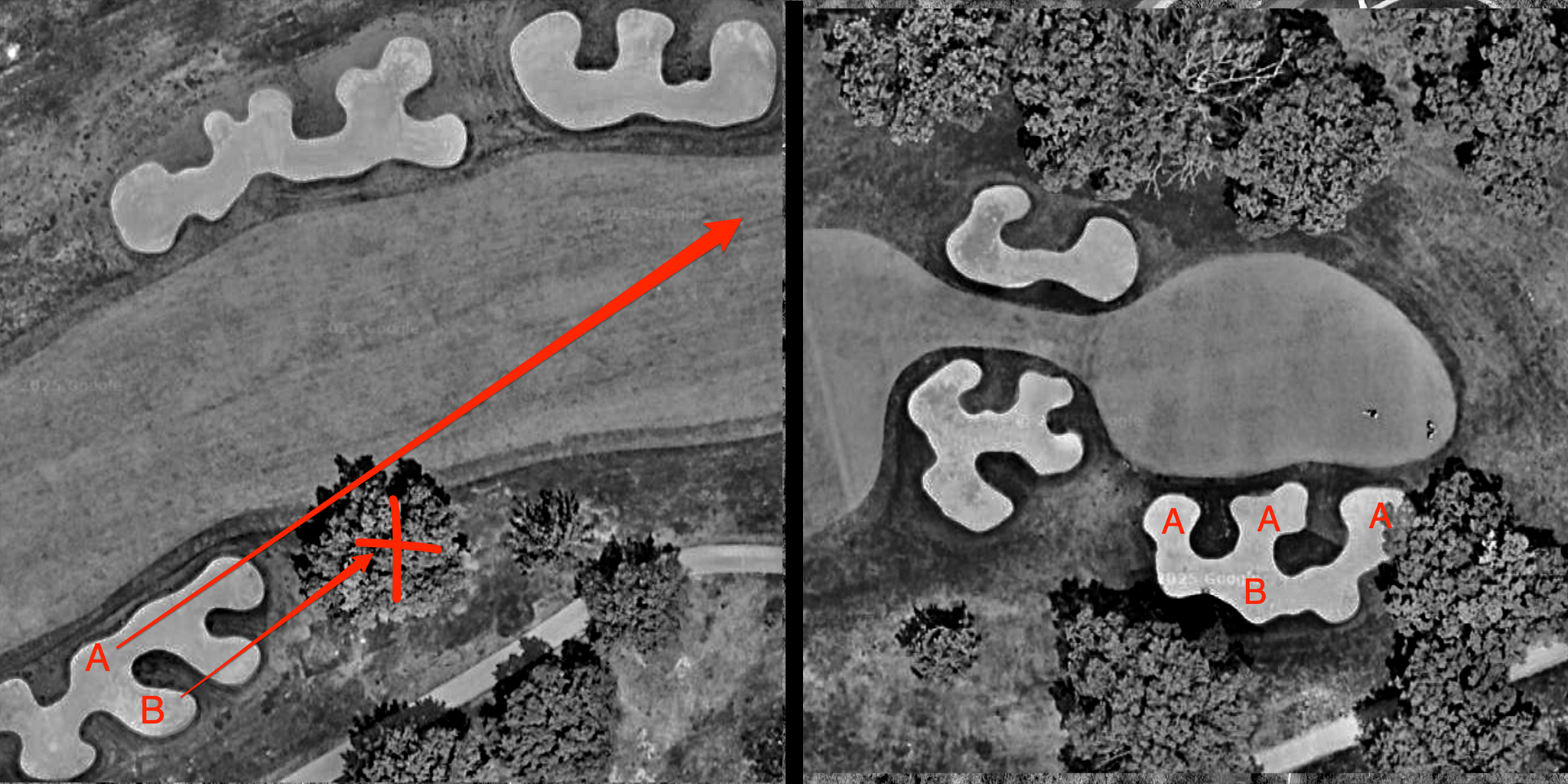

Another example can be seen by comparing a good example, and bad example, of Tillinghast’s signature “talon” bunker.

A good example is greenside right at Bethpage Black’s closing hole. Some note that Rees Jones made many of Tilly’s bunkers bigger during his infamous renovation but that’s okay in this instance. As we’ll see, this bunker still works effectively. The essence is that by missing near right, presumably when attacking pins on the right of the green, you’ll fall down into one of the bird’s fingers. If you’ve landed in a finger not in line with the pin position, you’re out of luck; the high berms in between the fingers prevent one from attacking the flag; a par will require a long putt from wherever you can get out to.

Guys like me, even if we land in the correct finger, controlling the ball out of that bunker is a tall order. Fortunately, we’re more likely than the five-handicapper to miss way right during our approaches. Hitting from the back of this bunker is no easy shot but hey, at least we’re not constrained by the finger channels. We can take any angle we want into this green. At our skill level, we’re going to need to hammer it. Does the angle really matter when we need to send it to the other said of the green?

Again, no one is given an “easy way out.” They’ve been given degrees of difficulty appropriate for their skill level…or lack thereof.

At no point is a bunker this big going to be “easy.” But by considering where certain categories of player miss, a bunker design can punish proportionally. (Photo Cred: Gogol’s Dead Souls)

At no point is a bunker this big going to be “easy.” But by considering where certain categories of player miss, a bunker design can punish proportionally. (Photo Cred: Gogol’s Dead Souls)

Jones took a few design cues from his time at Black and unfortunately applied them in ways that are bad. I mean, heck, it’s not like Cog Hill No. 4 was easy after Dick Wilson designed it the first time. But Jones’s 2008 renovation showed how the Tilly talon, applied incorrectly, displays how penal-era cruelty could impact the average player disproportionately (even more so than you might expect, that is). And Jones applied it a lot in the wake of his Bethpage acclaim.

Consider No. 5, a moderate-length par five. Here, this style of bunker rests on the right and, a little farther up, on the left, with the fingers extending away from the “palm,” which is relatively flush to the fairway. If the golfer misses just right, finding the bunker, life isn’t easy per se. They certainly can’t get to the green but they can take the longer iron they dare and play the slightest draw out to the fairway. If they can move it 125 yards from Point A, illustrated below, they’ll have a 140-yard approach for their GiR shot.

Those who miss 10 yards farther right, to Point B, are in considerably more trouble. The turf rises quickly around this “bay” of a finger, requiring a steeper escape shot. There’s a chance that, depending on your lie, you’ll need to hit backward to reach the fairway again, and that’s based on the molded topography alone. Just for good measure, you’ll need to hit a far more drastic fade thanks to the tree 30 yards ahead.

We can’t assume anything about the handicaps of those in position A or position B for any given instance. However, over time, we can safely assume that 100 players in position A will have a better mean handicap than 100 golfers in position B. Cog Hill continues to hammer the knuckles of the latter group using these exact misapplications of “Tilly Talon” bunkers.

At Cog Hill, Rees Jones’s attempts to make cool-looking bunkers (left) result in undue punishment for crappy golfers. Some of his green-side efforts, however, function better. (Photo Cred: Still Google. Not on the Bing train yet.)

At Cog Hill, Rees Jones’s attempts to make cool-looking bunkers (left) result in undue punishment for crappy golfers. Some of his green-side efforts, however, function better. (Photo Cred: Still Google. Not on the Bing train yet.)

To be fair: Jones’s use of this bunker style is applied properly at the green on No. 5 and several others around the Cog Hill property. Look to the right of No. 5’s putting surface and you’ll see the talon reaching toward the green. Again: This challenges the golfer who misses nearer more than those who miss far out.

You and Edward Blum can argue all you like that amplifying challenges for better golfers, while easing the way for higher handicappers, is unfair but while it’s strictly philosophy to argue strategic tenets, there’s a tangible pace-of-play issue that comes with the bad design examples provided above, both at the muni and the crowded club. Few architects struggle to challenge the best golfers…the best architects can do so while also keeping the rest of our rounds moving.

Those who can balance those two goals will often find themselves adhering to my mantra: “Miss nearly, pay dearly.”