Needless to say, I played both versions of The Loop when I visited Forest Dunes recently. Needless to say, I felt compelled to make a statement on which is better because – despite arguments from some ranking agencies – The Loop is not just one course. One groundbreaking form of landscape design, perhaps, but two courses to be sure. I concluded that, as in metal and coffee, Black is best. But why?

My knee-jerk reaction was that I appreciated how Black showcased a wide range of length in par fours, both quite short and quite long. It seemed counterintuitive that a separate course, Red, could diverge so much while sharing the same corridors. And so I came up with a formula for figuring out whether there was any meat on my theory’s bone.

There was (more on that in a second). And this opened the door to a separate question: Could the test I ran with The Loops be applied to courses more generally, to provide a relevant indicator of whether a variety in par four lengths correlates positively to course rankings?

Let’s find out!

If I really wanted to argue that The Loops should be considered as two separate courses and not one, I’d be able to name from memory what course this photo is from AND I TOTALLY CAN. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

If I really wanted to argue that The Loops should be considered as two separate courses and not one, I’d be able to name from memory what course this photo is from AND I TOTALLY CAN. (Photo Cred: BPBM)

First, back to the measure I used to determine the variance between the two Loops. I settled on a measure defined as the “mean distance from median” (MDFM). In other words, how far is the average par four from the median par four in a collection of holes? I considered using standard deviation to measure this (as a group of GolfClubAtlasers have recently done), however I believe MDFM tells a better story. By definition, one standard deviation presents a range and not a specific, single value – the range where 68 percent of the par fours sit relative to the mean. The problem with this measure for my purposes is that it doesn’t include the outliers (unless I also give you the second standard deviation), and the outliers – the most monstrous and most drivable par fours — are likely to be the ones that the average player remembers when thinking critically about a course.

Also, “MDFM” sounds like an industrial band.

At any rate, I calculated the mean-distance-from-the-median and then adjusted for a standardized distance, so each value presented below represents what the MDFM would be for each course in question if it played the same length as The Loop Black’s middle tees.

Let’s be clear about a few things before looking at some MDFMs from acclaimed courses:

- There are obvious shortfalls to this method. For one, it doesn’t consider the range of distances between the sets of par fives and par threes at a course, which is valuable information.

- For two, this stat only reflects the yardages themselves. They don’t consider important elements, such as whether these holes travel up or down, or along a Pacific coastal cliff, etc.

- All this is to say that you shouldn’t confuse a higher MDFM for “actually better.” Realize that we’re trying to find a correlation between whether they’re ranked better as a result of higher MDFM scores.

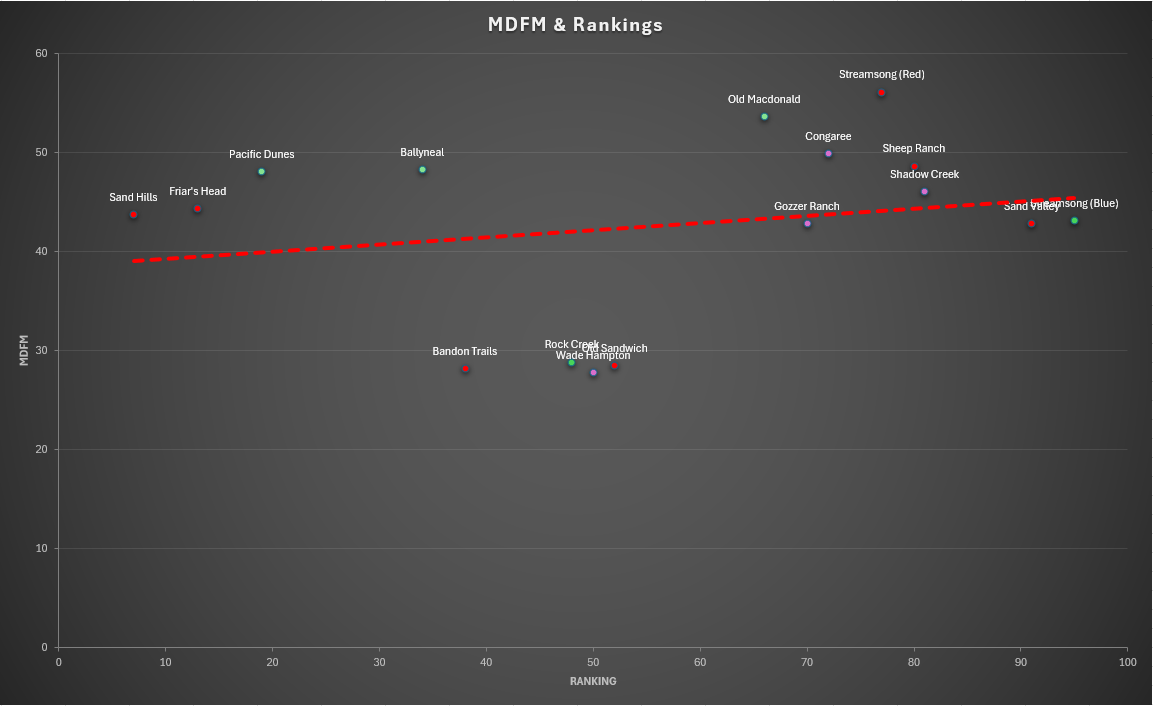

As a test sample, let’s start by looking at three architects/firms – Tom Doak, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, and Tom Fazio – two of which are held in high regard by the current waves of architectural thought, and one who isn’t. Furthermore, we’ll look at their respective courses within GOLF magazine’s U.S. Top 100 rankings (editor’s note: These numbers are based on the 2022-’23 ranking, the most up-to-date at the time of writing). Do the designs of Doak and C&C show significantly more variance within their par fours than those of Fazio?

In case you don’t read the rest of this post: The trend line (which, for the record, is not backed up by a large enough sample size to be taken seriously) is heading the opposition direction as what my thesis would have suggested. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graffix Dept.)

In case you don’t read the rest of this post: The trend line (which, for the record, is not backed up by a large enough sample size to be taken seriously) is heading the opposition direction as what my thesis would have suggested. (Photo Cred: BPBM Graffix Dept.)

After looking at the data, we ask the big question: Does this limited data set support the idea that courses with higher MDFM among their par fours are ranked higher? So far, no good. For anecdotal purposes, it’s interesting to note that Doak’s Old Macdonald has a higher MDFM than its Bandon counterpart, Pacific Dunes, which is near-universally held to be the better course (although both have high MDFMs relative to all golf courses). Similarly, Coore and Crenshaw’s Sheep Ranch displays way more variation than Bandon Trails, which – again – is more often celebrated as the better course.

If our hypothesis was correct, the top-ranked courses would be the upper-left of the chart, well-ranked and among the highest in terms of MDFM. If anything, the trend line seems to suggest that the opposite is true; MDFM has actually increased as rankings get higher. Take that with a grain of salt, however. The chunk of courses in the middle of the rankings have significantly lower MFDMs than those at either extreme. In short, the trend line exists only due to a low level of data. There’s not really a “trend” at all.

As a side note, the battle between Doak/C&C and Fazio doesn’t amount to much in this measure, either. Sure, Wade Hampton comes in relatively low (27.79) but that’s not a far cry from Bandon Trails, Rock Creek Cattle Company, or Old Sandwich.

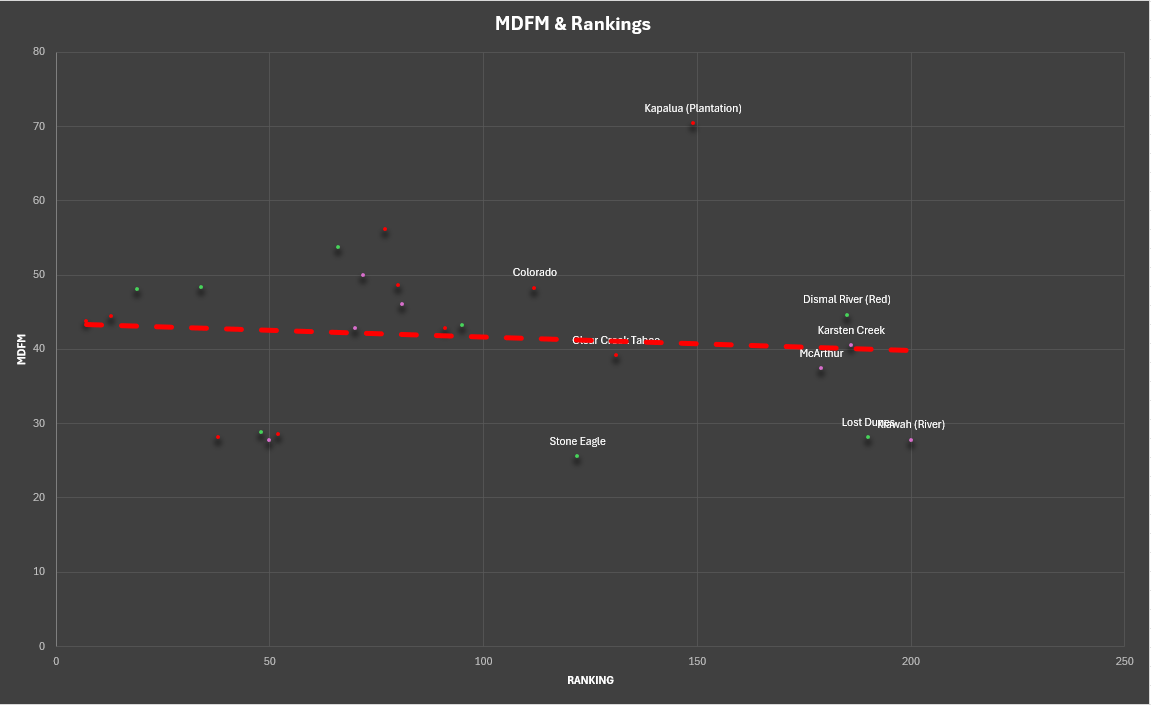

Still, we can’t write off the original hypothesis entirely. After all, we’ve only compared courses in GOLF’s Top 100 thus far. What if we were to compare these courses and their MFDM to courses in the next 100? Being that GOLF doesn’t publish a “next 100,” we’ll rely on the course list of another publication that does: Golf Digest.

How do the “next 100”-ranked courses by these same architects compare to their work that sits in the Top 100? Let’s take a look:

When Busta Rhymes saw how far a certain course was from the expected MDFM score, he yelled, and I quote, “Kapa-woo-ha woo-ha!” (Photo Cred: BPBM Intern Jeff)

When Busta Rhymes saw how far a certain course was from the expected MDFM score, he yelled, and I quote, “Kapa-woo-ha woo-ha!” (Photo Cred: BPBM Intern Jeff)

Well, on one hand, when looking at the respective architects’ bodies of work within our “Top 200” ranking, we do see the trend reverse somewhat, indeed reflecting a slight decrease in ranking to be expected with a decrease in MDFM. That said, this trend line (especially when considered against the trend line we saw for the Top 100 alone) hardly does anything to convince me that there is a serious correlation between the two factors.

Perhaps the most damning piece of evidence is Kapalua’s Plantation course, which truly dropped my jaw when looking at the numbers. Its 70.412 MDFM from this exercise is 14 yards higher than that of Streamsong’s Red course, which itself was this exercise’s second-highest tally. Furthermore, it’s 27 yards more than that of Sand Hills, the highest-ranked course featured in the exercise. Considering that all three were designed by Coore and Crenshaw, it suggests that MDFM is less-than-likely to play any role in a course’s final ranking.

The good news is that this exercise hasn’t been a total waste. Although there are obviously outliers in both directions, there’s also a decent body of evidence to suggest that Doak and the Coore-Crenshaw collaborative, perhaps the two biggest names in the “new Golden Age,” are more inclined to create a variety of par four lengths than Fazio, the figure whom they are perhaps most frequently contrasted against.

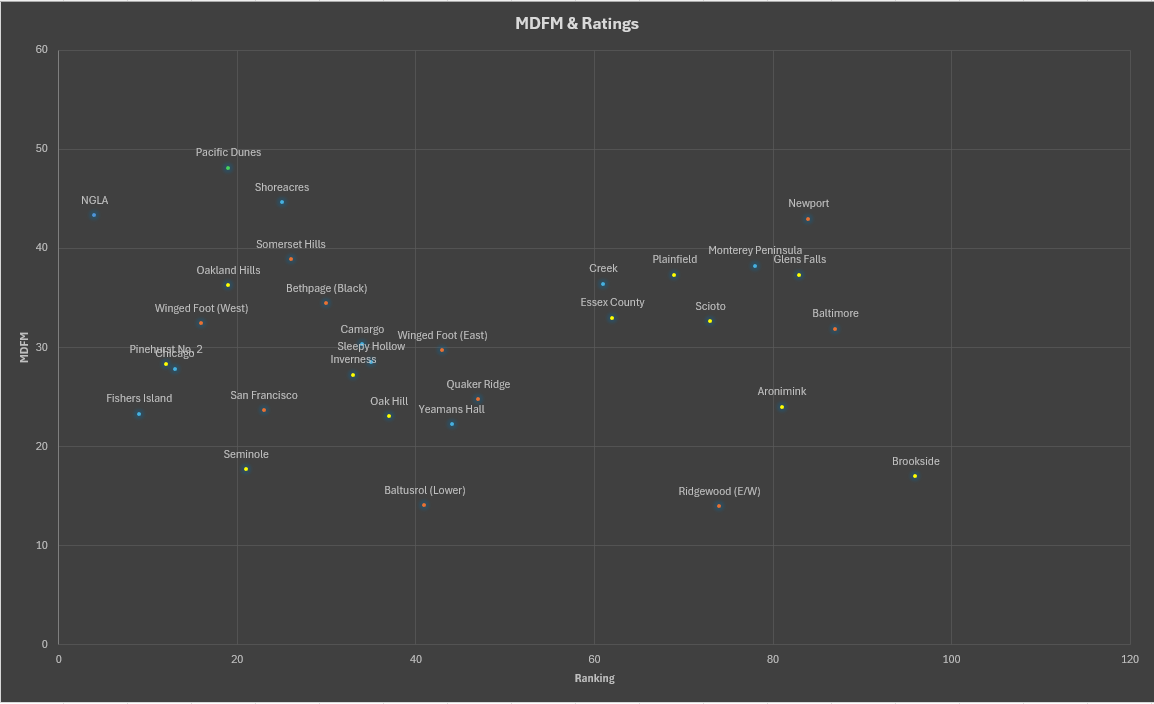

That begs the question of how MDFMs of these architects compare to those of the original Golden Age. We can run a similar exercise, calculating the MDFMs for the courses featured in GOLF magazine’s U.S. Top 100 for the most popular designers of that era. The individuals with the most entries on that list are Donald Ross, A.W. Tillinghast, and the MacRaynor collective. Let’s chart their designs and see how prone to par four distance differentiation these guys were.

Yeesh, did the Golden Age greats differentiate the distances in their par fours at all? Yes, but not very much compared to Tom Doak and his modern colleagues. (Photo Cred: BPBM Intern Adam)

Yeesh, did the Golden Age greats differentiate the distances in their par fours at all? Yes, but not very much compared to Tom Doak and his modern colleagues. (Photo Cred: BPBM Intern Adam)

Interestingly, not at all. Look at the yardages on the Y-axis…I included one entry from the previous list, Pacific Dunes, for comparison. Not one of these iconic courses out-MDFMs Pacific. Only three of the Top 100 courses from these guys even cracks the 40-yard mark in terms of MDFM.

Just for kicks, I ran the MFDM for my local Jack Kidwell-designed residential course. The result? It’s got roughly the same score as Fishers Island. I don’t think anyone will confuse the two when determining which is the stronger design, despite that fact.

It’s an interesting finding, because it allows us to note a key difference in the current “golden age” compared to the original. Two commonly shared notes on the Doaks, Coores, Hanses etc. has been their predilection toward sandy sites (versus an acceptance of parkland locations among the original Golden Agers) plus a more aggressively minimalist aesthetic. These numbers suggest another divergence, in that modern architects are more adventurous in how long or short that they’re willing to stretch, or tighten, a par four…not just once but many times across a single course (our original example, The Loop, is case and point).

I hazard to suggest that it’s because modern course architects are less handcuffed to the strokeplay concept. Although I myself have often argued that a matchplay mindset provokes better design, the designers of championship courses during the original Golden Age were more beholden to strokeplay’s needs; although the PGA Championship maintained matches until 1957, the older U.S. Open always counted strokes, as did The Masters when it debuted.

As more courses openly promote matchplay – whether it’s demanded, in the case of Ohoopee, or encouraged by the no-tee-markers approach of Ballyneal – architects can breathe a little easier and worry a little less about red and black numbers, promoting the par four distance diversity that we’re seeing today. Despite weekend golf culture itself still being well-rooted in the strokeplay format, there has been little resistance, based on ratings, to these match-friendly courses.