Blind approach shots make for uncomfortable discussion among “woke” golf course architecture folks. On one hand, the idea of simply launching a ball into space and trusting your distance is not a hip concept to those committed to the “Strategic School” of golf course architecture. How much “luck” should be required for something that’s allegedly strategic? On the other hand, even C.B. Macdonald could not deny the appeal in the original “Alps” at Prestwick, bringing the concept back to his American designs. Very few have the backbone to suggest Macdonald is “wrong.”

At its base are two contrasting values. The second value is the principles of Strategic golf, which places almost all emphasis on the player; both their ability to gauge risk and reward, and execute upon them. But golf’s roots in the Scottish links relied on a bit more. It relied on luck. Great courses require great players to execute strategically, but it also requires them to react to wild bounces and curious results. Blind shots into punchbowl greens are more at home in this philosophy.

And so there’s some uncomfortable thumb-twiddling when the idea comes up in modern architecture conversation. The intrigue and suspense of walking up to your ball after launching it into the (relative) unknown, versus the inherent unfairness in blinding the green.

Pete Dye takes an alternative tack to the blind approach at Pete Dye Golf Club. In fact, he does it three times.

His logic: A blind shot is more fair if the player can see the green.

Sounds like crazy talk, but let’s step back and consider what goes into a “good” blind approach. I would argue that the longer the shot, the better it works as a blind one. A hole designed to require a short approach after a good drive should be focused on the second shot’s accuracy. If the green requires a bomb upon approach, even after a good drive, a player’s expectation for accuracy is diminished. In other words, a blind second shot will be more acceptable. Using this theory, Dye applied a similar technique to three holes at PDGC that justify three shots to reach the putting surface.

Normally, these conversations revolve around either tee shots to a blind fairway, or approach shots to a blind green. Dye flips the script by letting you see the green. What you can’t see is the stretch of fairway leading into that green, which you’ll inevitably use to arrive.

Let’s consider, for example, the first hole featuring this phenomenon at PDGD: No. 5, arguably the course’s best hole.

If playing from a more human set of tees (the Championship set greatly lengthens the hole), a realistic drive will take you toward the end of the Par 5’s lower fairway (which ends 310 yards out from the 6,750 tees). Let’s say you hit it decent, maybe 275. When considering your approach, several items will interest you. The first is the elevation rising up to the fairway’s second level; the fairway snakes left up the hill, but your shot will be straight over a series of six bunkers built into the side of the hill. More relevant to your approach is Simpson Creek, which runs along the right side of the hole, but doesn’t come into play until the final 130 yards. And then, in the middle: The green.

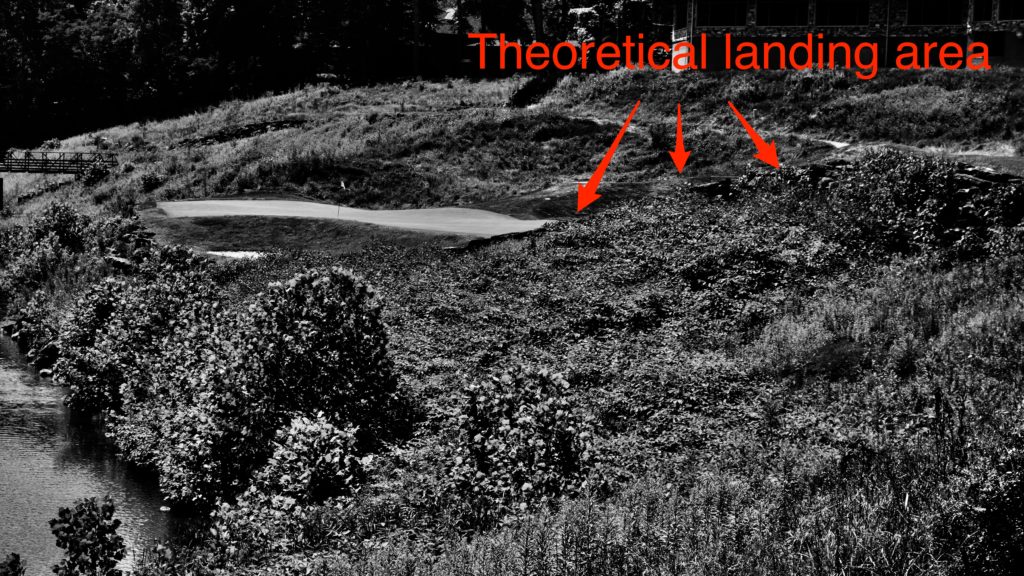

What you won’t see is the last 250 yards of short grass.

The distance between you and putting surface plays an interesting trick on your perception, almost seeming lower than the top of the hole in front of you (it isn’t). At 250 uphill from the theoretical shot, you’re not looking to reach the green. The question is how far to lay up. The first 100 yards of the upper plateau is among the widest stretch of fairway on the course…about 65 yards wide. From 100 yards in, it tightens to perhaps 1/3 that distance, with bunkering and the creek enforcing the approach. The obvious next move is to lay up as to have a full wedge in. And yet…you think about it. Why? Because you can see the green.

The second shot up to the second level is uncomfortable because of its blind nature, but at least you know the shot is safe unless you really screw up. The short ball is the essence of taking small steps in a dark cave. Dye, however, is an angler fish, and he has extended the glowing light of the green into your view to make your dumb fish brain think about swimming toward it. The boldest and best may reap a simple approach into the smallish green. Those who are merely bold will find their third shot much more complicated. Or wet.

Are you wise to Dye’s mind games? Not tempted by the green’s visible allure? Good for you! It won’t be so easy when you get to No. 8.

No. 5 could potentially be reached in two by big hitters. No. 8 is designed to be reached in two by damn near everyone. This hole is arguably too easy for strong strokeplayers, tipping out at just 504 yards and playing drastically downhill. But Dye designs for matchplay.

PDGC is not “mountain” golf, despite its West Virginia location, but this hole may disagree. The first 300 yards play fairly flat, before diving dramatically for the next 200. Let’s say you hit 275 again, and consider what catches your eye.

First, there’s the green. It’s considerably below your feet this time and just 205 yards away. Still, it’s also a particularly skinny green, which falls off significantly to the right. To punctuate the challenge of this lower area, Dye added one of his largest-ever bunkers, snuggled up against a stone mountain face (banking off of said mountain will not help). Shots to the left will find a friendlier pitch, if not a friendly pitch, in a fairway gathering area. There’s penalty long.

Although doable from where you sit, the more realistic way to an eagle putt is by riding the fairway down to the front of the green. From where our theoretical shot sits, that second stretch of fairway is now on the left, guarded by the aforementioned valley on its inside. The good news is you can see the fattest part of the fairway, as it’s below your feet this time around. The problem is this “smart” layup means hitting a shot of less than 150 yards, and doing so on a Par 5 that’s only 495 to begin with. It’s a classic matchplay case where playing too conservative is self-sabotage. The alternative is to find the sharpest part of the fairway’s descent, about 50 yards out from the green. It’s also the skinniest part of the fairway’s descent, and—you guessed it —a blind landing zone from your position. A great shot can kick down to the green. An OK shot may miss to the left of the geren, for a manageable up-and-down. Poor execution can end up anywhere; down in Dye’s valley (ha, puns), in the rough to the left of the chute or, potentially the worst case scenario, in the pair of bunkers to the left of the chute.

The green is just there staring at you, but the road there is foggy.

The last entry in this series, and the last entry in your round at PDGC, is the closing hole. This, although a Par 4, reasonably plays at a higher average score than No. 8, both because of its similar length (476 from the tips) and the kind of challenge you’d expect from a Dye closer. Aesthetically, it resembles the designer’s go-to finalist, a long par 4 featuring a water hazard along the inside corner. You’ll tee off across Simpson Creek, but your view home will be much different than at Sawgrass’s finale.

Again, you’ve hit that 275-yard shot from the tee, leaving 195 in. Your landing area will impact the next shot: The fairway slopes graciously from right to left, so many will drive far from the evils of Simpson Creek and let the ball glide down to the center of the fairway. They’ve been duped. The green is lower than most expect, and approachers won’t be able to see it when hitting over the crest of the slope down to the green. This is the kind of traditional blind shot many architectural aficionados will express distaste for. From a member’s perspective, however, it’s a home-field advantage. After all, those in the know will find a more attractive view.

As with most of Dye’s pseudo-capes, the closer to the hazard your drive lands, the better off you’ll be. Still, it’s a spooky angle. Near the far left of the fairway, beyond the two bunkers, you’ll be able to see where the green rests (and another nice Simpson Creek view). As with No. 8, you won’t be able to see the fairway area that rides onto that green, because of a “peculiar” (AKA “constructed”) hump that rises at the corner, 66 yards out. This 44 yard-deep green features many segments, divided by its ever-changing roll. Finding the right one will make the difference during a match. This approach is unique versus the last two we discussed because riding the blind fairway slope isn’t strictly necessary. The bold can consider sticking the green from 195 out, but the angling of the green from this angle (front-right to back-left) makes it less-than-guaranteed.

Let’s recap, mostly so I can make sure my own thoughts are salient:

The biggest problem with blind approaches is that the chance to score is based considerably more on luck than the average approach, even in the best of cases, which understandably raises flags in the minds of fans for the “strategic school.” A blind shot is an inherent risk, and one that doesn’t come with a safer alternative. It could be argued then, that blind shots are best utilized in “half-par” holes—such as drivable Par 4s, short Par 5s, or beastly 4s like the Road Hole—where players’ expectations are flexible regarding when they should land on the green. If reaching the green in two on a short Par 5 requires a long, blind approach, they may opt to stay short rather than dare the risk of the unknown.

Dye’s work at PDGC adds another layer to this algorithm, however. He knows that you know the risks behind a blind shot, so he needs to offer something to sweeten the pot. So he shows you the green, the very thing on the other side of that blind murk, to lure you into a bold move. It’s like the “free shipping” attached to an attractive eBay item. If the green were hidden, or the shipping price set to $4.77, you’ll withhold. But he baits the hook and dummies like me bite (both at PDGC and on eBay).

Good blind shots are more than just risk/reward tactics, however. Strategic golf requires confidence from the player that he can execute on risky shots. No one is more equipped for a blind shot than the player confident in his distance, and his ability to execute on it.

But for the rest of us? We frequently note Pete Dye’s use of visual intimidation. Perhaps we should pay more attention to when he makes it look less intimidating than it is.