I recently had the privilege of appearing on the National Links Trust Podcast, speaking with Will Smith generally about the state of municipal golf in the United States (there’s also an early moment where I use my oft-repeated corpse metaphor to differentiate between black and death metal but, for the most part, golf was the topic). More specifically, Will – like most of you – realize that my primary draw on social media is bringing attention to smaller projects that don’t get as much love in bigger publications, so we discussed the macro-trends at play with municipal courses around the country…not just the National Links Trusts and Cobbs Creeks of the world.

That’s when he hit me with an interesting question: What municipal project am I following most avidly? I didn’t have an immediate answer; firing from the hip, I cited Todd Clark’s work at Swope Memorial, being that I’m a Tillinghast fan.

Driving home later, I thought more deeply about what the answer might be. I realized that there’s one project rooted deeper in my ideals as a golf course architecture hobbyist and, more importantly perhaps, as an environmentalist.

That project is Westport Golf Links, which will theoretically be located 70 miles west of Olympia, WA on the Pacific coast.

One big clarification I owe you: This isn’t, technically or actually, a municipal golf course. It could, however, serve as a major mover to inspire golf-related developments at every level of park in the United States. This is a concept I’ve annoyed countless listeners with for years.

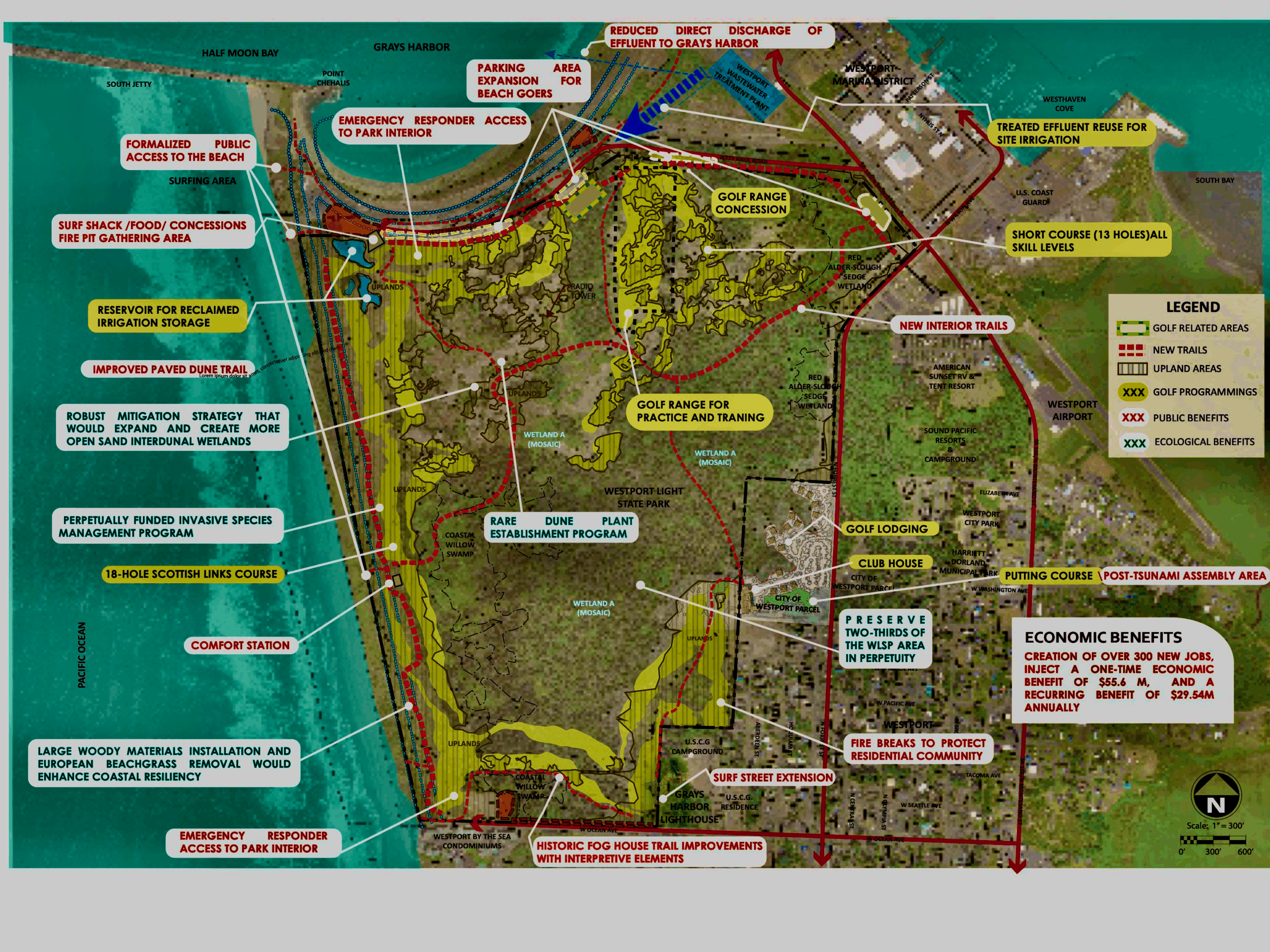

Westport Links is, at its core, an 18-hole Bandon-style links golf course with an accompanying 13-hole short course, designed and built among dunes on the Washington coast by David McLay-Kidd. That, in a vacuum, is enough for most of my readers. More important to your correspondent is the formal location of this course, which is within Westport Light State Park, a holding of the Washington State Parks system. The project’s developers have collaborated with Washington State Parks and the city of Westport to create a plan that both allows for what will surely be a great golf course and increases accessibility to the park’s trails and beaches. Economic impact studies suggest it will create 350 local jobs. Again, great.

Still…if you’re a hiker or general admirer of nature, such as myself, you’re more than justified to be skeptical when someone proposes developing anything, much less a golf course, within a state park. Fortunately, this is an instance where – thanks to the park system’s involvement – environmental impact has been assessed and approved.

So now we can turn our attention to something that is truly the biggest threat to park systems across the United States, at every level of government. It’s not golf course development. It’s not petroleum drilling.

It’s funding.

In case you hadn’t heard, the concept of government “efficiency” has been en vogue. The Trump administration is advertising a billion-dollar cut to national park funding. One can expect that governors across the nation will follow suit for state parks and state forests. Politics might not be the only thing to blame; as the American population ages and largely becomes less healthy, more and more cash will be allocated to social services. People vote more than trees. The average national park or national forest does not run in the black. Hunting and fishing licenses are a major generator of revenue, as are passes for hiking, camping and other activities, but these aren’t offsetting operational costs.

My concerns for the park systems and their budgets began long ago and they haven’t lessened. A plan such as Westport Links, executed properly, serves as a direct IV of liquid assets into a potentially dehydrated property. The state both draws less from its coffers to maintain that asset, and that asset has the potential to subsidize other properties around the state by filling the state’s till. This is, simply, good business.

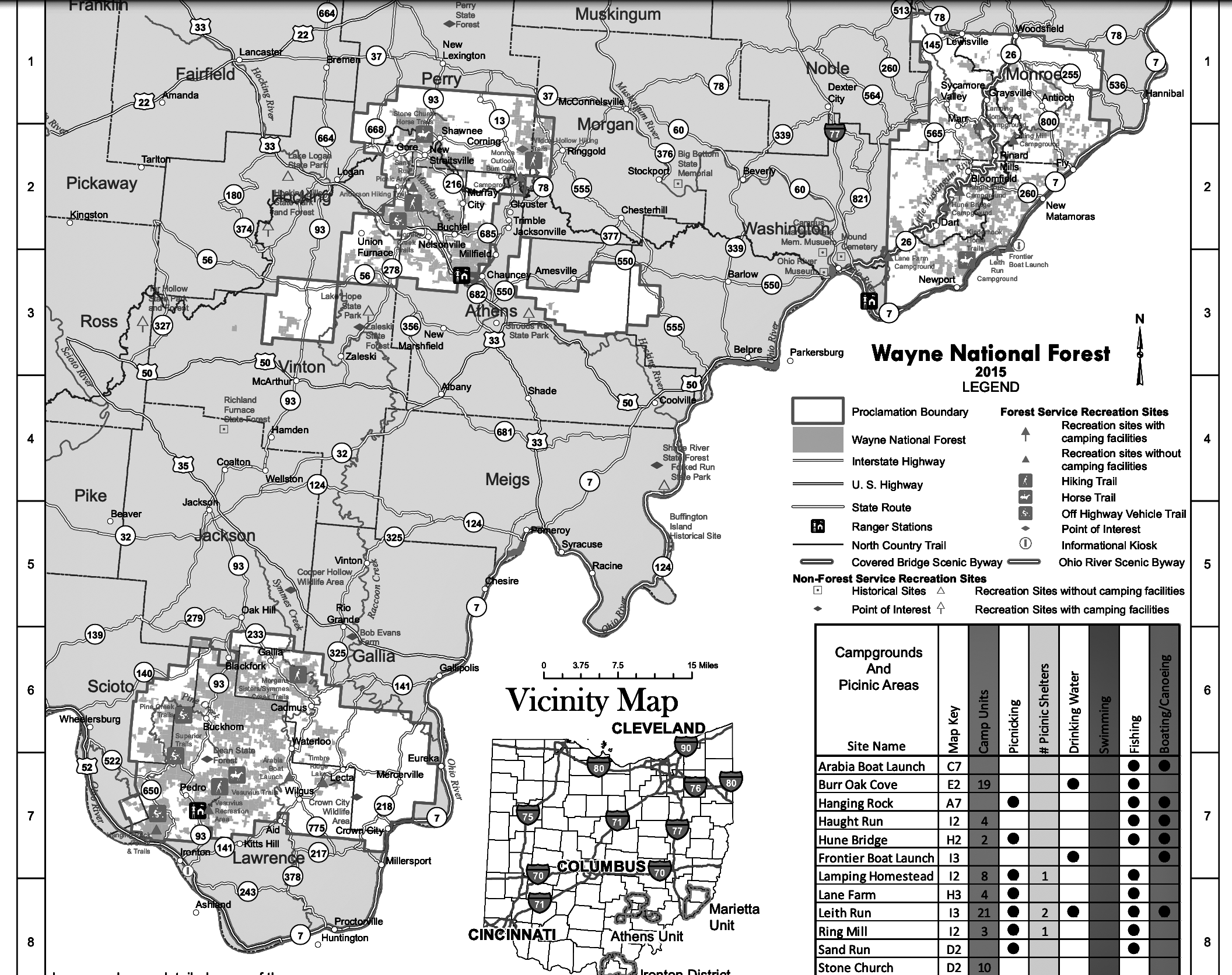

Can every park sustain such a project? No. Again, the goal of protecting and sustaining natural habitat must come first. More parks have land to give with minimal environmental impact than you might imagine. I’ve often mused about the potential for a 45-hole resort located at Ohio’s Wayne National Forest; it sounds slightly but Ohioans realize that huge swathes of that entity haven’t featured trees for centuries. They were clear-cut and continue to exist as the state’s least economically viable agricultural land. Assuming one could patch together a plot for such a resort, there is suddenly a tourist draw within three hours of four “professional sports”-sized cities. Whether they stay and hike is beyond the point, if the park gets paid.

Still have doubts? If you’ve visited French Lick, Omni Homestead or Forest Dunes – just to name a few in my neck of the woods – you’ve likely played a top-tier public golf course that’s built on national forest land. A project such as Westport proves that such products can more directly benefit the land on which they sit.

Unfortunately, recent events – namely the Jonathan Dickinson debacle – have cast a pall on what could, employed in good faith, be a mutually beneficial model. Unfortunately, very little seemed to have been done in good faith there.

You can read the full details here but here’s the gist, with problematic parts flagged: A charitable organization circumvented Florida’s park system’s input (bad) to create a series of golf resort properties via executive decree where, at least in the showcase Jonathan Dickinson example, the courses would sit on sensitive ecosystems (bad) and cash would flow to a charity unaffiliated with funding the parks themselves (I don’t want to dump on veteran charities…but use of state park land for this purpose is draining Pyotr to pay Pavel).

Granted, there were some winning ideas in Folds of Honor’s master plan. For example, the organization’s plans for Florida Caverns State Park involved recycling the shuttered golf course on the property. Sure! Why the heck not?

I can take pleasure in my hobby of choice, knowing that it’s not killing the planet circa 2025. The industry’s employ of water and chemicals continues to decrease on a yearly basis. Audubon-certification is eagerly pursued. As temperatures rise and hurricanes continue to batter the coast, parking lots won’t be cooling the planet or serving as floodwater outlets. Golf should seize the initiative and actively promote itself as an environmental good.

Serving as a permanent fundraiser for at-risk park systems is as good an opportunity as any.