A.W. Tillinghast was not a fan of templates.

“I have known Charley Macdonald since the earliest days of golf in this country and for many years we have been rival course architects,” he wrote. “Our manner of designing courses never reconciled. I stubbornly insisted on following natural suggestions of terrain, creating new types of holes as suggested by Nature, even when resorting to artificial methods of construction. Charley, equally convinced that working strictly to models was best, turned out some famous courses. Throughout the years we argued good naturedly about it and that, always at variance it would seem.”

That is, Tillinghast was not necessarily a fan of MacRaynor’s template philosophy when it came to MacRaynor’s own template holes. Tillie approved more so of his own concepts, which include the “Reef” and “Double Dogleg” (his “Tiny Tim” was, for all purposes, just a different term for “Short”).

One has gathered more acclaim than those, however: The “Great Hazard” (frequently cited as “Tillinghast’s Great Hazard”…which probably fed into the architect’s noted ego).

This template may have made more appearances because it played relatively well into Tillie’s “naturalist” approach (implied above). Any large portion of flattish land can be covered in sand…unlike, something such as a Reef, which requires very specific qualities from the land it sits upon. The massive hazards at Pine Valley (Hell’s Half Acre), Bethpage Black, Somerset Hills and others only have two things in common: They’re huge bodies of sand, and they impact the second shot on a Par 5.

Tillinghast didn’t add Great Hazards like Tom Weiskopf adds drivable Par 4s…not every Tillie design has one. But the idea was never far from his mind…even when he approached the least tenable property available. This brings us to Sunnehanna Country Club, located in Johnstown, PA, among the state’s Laurel Highlands.

We’re not Golden Age logistics experts, but we would suggest the course’s location was simply too high to transport enough sand for a Great Hazard. Sunnehanna is the highest course that Tillie ever undertook, in terms of altitude. Many New Yorkers may Google Johnstown’s altitude (1,142 ft.) and protest this fact, but this Sunnehanna actually sits within Westmont, PA—less than two miles from downtown Johnstown…but located at an altitude of 1,750 ft. This difference in height explains the city’s famous 900-foot inclined plane. It also explains why after Andrew Carnegie and his rich buddies altered a local dam for their hunting club, a downhill rush of liquid devastation destroyed the city in one of the worst floods in American history.

It thirdly explains why getting sand to Carnegie’s next project—Sunnehanna—was a chore. No cities were destroyed in this instance, but the literal horsepower required to chug that much sand up a mountain…J.D. Rockefeller might have that kind of cash, but broke-ass Andrew Carnegie? Maybe not.

Nonetheless, a Tillie wants what a Tillie wants. And if you look at the original layout, currently hanging in the clubhouse (above), you’ll notice a couple bunkers bigger than the others. At the far left is No. 11, and closer to the bottom of the image is No. 15. These represent Tillinghast’s best attempts to create a Great-ish Hazard with less-than-Great options. The results will never match the potential of a full Hell’s Half Acre, but there’s effectiveness here to mess with even the course’s best players; participants in the annual Sunnehanna Amateur Championship.

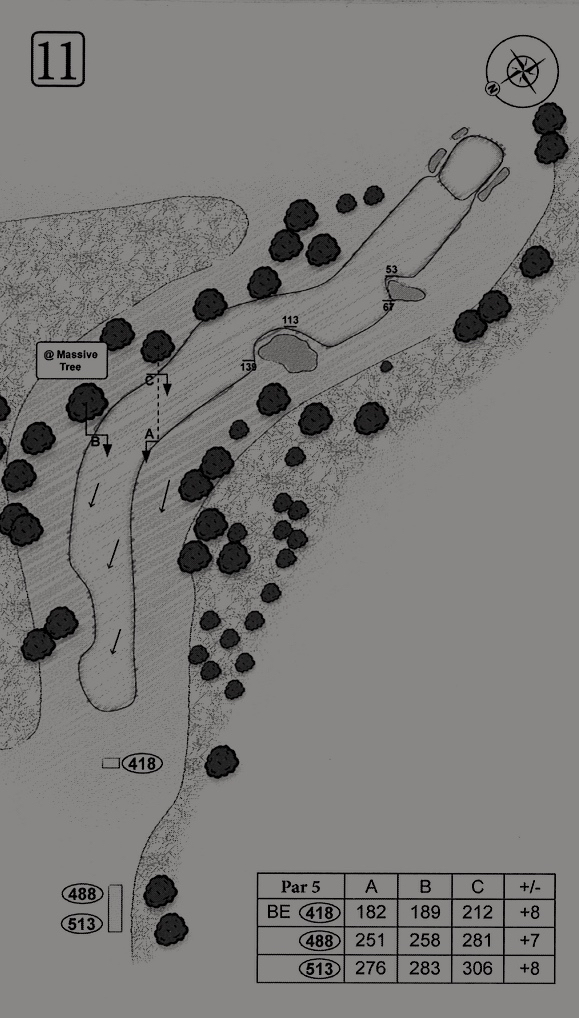

Let’s start with No. 11, an awesome hole, but not quite as awesome as No. 15 (no offense, No. 11).

This hole is more interesting from a renovation standpoint, however. The case study at No. 15 has never disappeared during Sunnehanna’s history, but No. 11’s was only recently restored by Brian Silva. The downside, compared to No. 15, is that this mini-Great probably won’t screw with too many competitors at the Sunnehanna Amateur. Sitting off the right side, this deep pit would take a 320-yard drive, uphill, to reach from the tee. Such a drive would only require an 140-yard wedge down to the green, so most hammerheads are going to lay up. Fools like you or your correspondent, however, only need about 250 to reach the top of the hill, and that gets us to thinking about cutting the sharp dogleg right. That’s how we end up sitting in deep rough on an awkward slope, as the hole wraps the edge of a steep drop-off. And that’s why we try to make up some ground in our recovery wedge, and end up in this thing. It’s possible to reach the green from the bunker, but it’s also possible to land in the three bunkers edging the green. This is also one of many greens at Sunnehanna that are both Stimped at 13 and roll downhill from the approach. It’s difficult to position yourself for an eagle, even when approaching from the fairway. This is a “must-birdie” for Sunnehanna Amateur competitors, and a matchplay killer if you—an even less professional golfer—can’t reach in three.

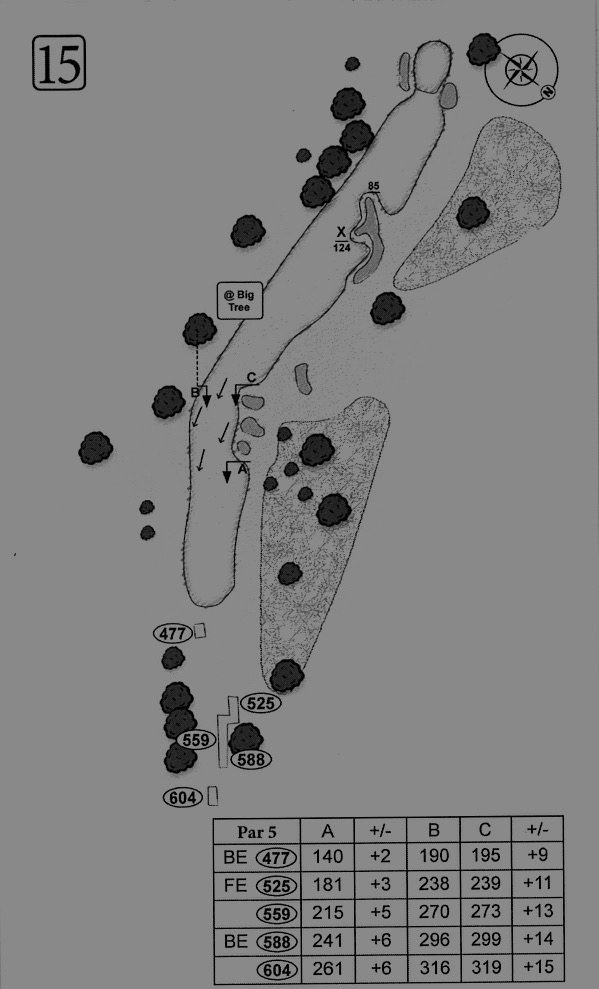

No. 15 is more impressive because of how well its varying bunkers, including the mini-Great, network together.

It’s a more traditional length (595 yards) than No. 11, and its lighting-bolt (or maybe just an “F”) cross bunker serves as a more traditional “Great Hazard.” Is it so colossal that you could get stuck in there for several shots? No. In fact, at first glance, it seems almost comically shallow. Even your correspondent took a stab at the green (120 to 160 yards away, depending on where you end up) while sitting in it. This could have led to disaster, and fortunately it did not.

Sunnehanna has many elements that seem out of place for a Tillinghast design, such as greens that feature Raynor’s geometric aesthetic (perhaps Carnegie had snuck a peek at Raynor’s ongoing work at Fox Chapel while home in Pittsburgh). The green-side-left bunker at No. 15 is even more in line with the approaches of ol’ Seth, “Steamshovel” Banks, and the Langford/Moreau conglomerate, thanks to the depth and steep ascent required to escape. I haven’t checked my facts, but I don’t hesitate to label it the deepest on the course. If you’re in the cross bunker, a short iron or even wedge might get you to the green, but if you can’t control your downhill distance from a sandy lie, a truly punishing hazard awaits.

The mini-Great-to-greenside tandem exemplifies the “networking” we mentioned. This theme exists from the beginning of the hole as well. Although it’s possible for a more casual duffer to hit the cross bunker from the fairway, no competitor in the Amateur will have the same concern. Tillinghast’s design therefore tempts more powerful players to cut the corner, and this is where they get into trouble. For one, there’s a wonderful set of three bunkers stacked in rising altitude along the turn. One of Sunnehanna’s strengths is that so many of the fairway bunkers are invisible from the tee, obscured mainly by rough. It doesn’t make for good golf porn calendars, but it rattles players inexperienced with the course, even when the yardage guide tells them exactly where the hazard is located. You land in this stoplight-style formation, and it’s unlikely an everyday player moves toward the green with their second shot. Theoretically, if you’re a player as talented as Patrick Reed or Justin Thomas (two guys my caddy Bob—”Bahb”—carried for during the Amateur), and you have the angle, you could be tempted. Likewise, if you end up in the right rough (Silva led the removal of a huge section of trees over the past decade, making the right side more tempting), you can’t see how far that cross bunker is. The wise play is probably to lay up short of it…but it awaits those with tragic, Macbethian ambitions.

Just like with Hell’s Half Acre. One “Great” may cover a lot more ground, but they essentially cover the same purpose: “Can I get over in two?” A shot in the rough definitely means “no” at Pine Valley, but it at least generally means “no” at Sunnehanna as well. The good news at the latter is that you can still get on for a GIR from No. 15’s pseudo-Great…not so much at Pine.

Silva’s renovation master plan showed intent to fully cross the fairway with the mini-Great from No. 15, but we’re not sure it’s fully necessary. This bunker has stayed largely unchanged since the opening of the course, and it maintains its role to this day.

That’s a rarity, however. Although Sunnehanna is running at full steam circa 2019, there was a significant down-period, in line with complaints heard regarding much of the golf world during the latter 20th Century…shrinking fairways and greens, disappearing bunkers, and an excess of trees…all of which impact the playability of Tillinghast as much as any other architect. Ron Forse led the charge tackling the fairway and green sizes, and Silva’s restoration of the bunker at No. 11 and elsewhere has lent a new lease on life to Sunnehanna and its namesake tournament. Further improvements are in line, according to those in charge at the club. Membership should look forward to them.