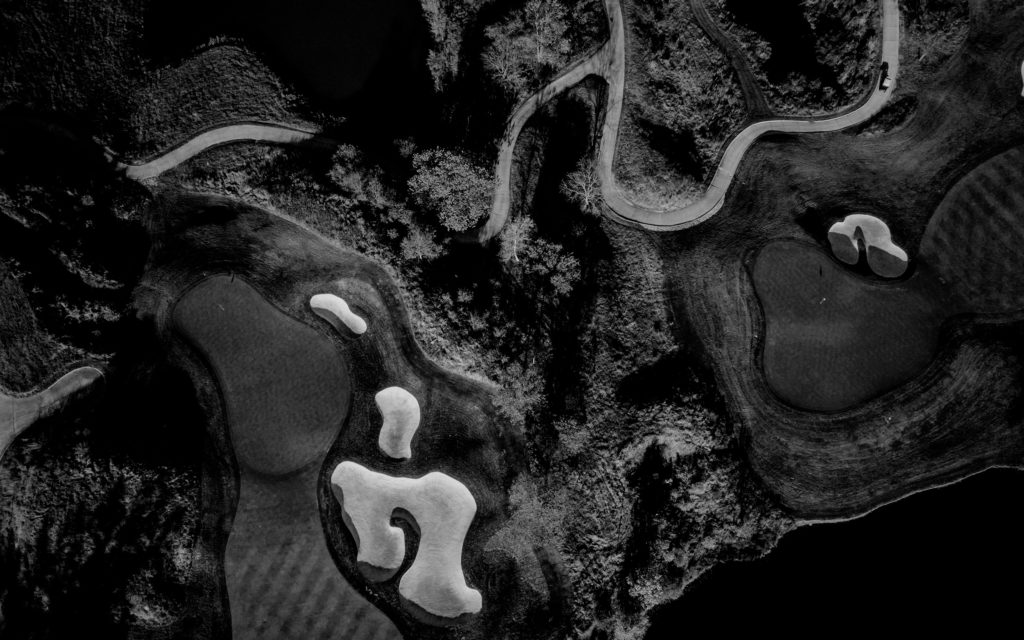

Big weekend for Korn Ferry (at least the Tour), as the first in a decade’s worth of Tour Championships took place at Victoria National. Some projected that scorecards could border on the U.S. Open-at-Shinnecock…because that’s what happens to every other human being who plays at National—it’s basically Tom Fazio’s take on Whistling Straits…if ponds replace the bunkers. The European Tour’s Tom Lewis thought otherwise, shaving 23 strokes off par to take home a win.

But again: If us normal folk were to play Victoria National, we would lose a few.

It’s not Fazio’s fault (believe-it-or-not) that Victoria National is the wettest thing in Indiana, discounting Lake Michigan and the Ohio River. The course lies on a former strip mine, and you gotta do something with the strips. Even if you don’t fill them with water, there are still massive canyon features across the property, which will almost assuredly kill your members when they drunkenly drive into them (ponds are more forgiving, although drowning still possible). Not every golf quarry needs water; Fazio’s titular “Quarry” course at Black Diamond Ranch plays five holes across a much broader man-made crater.

Quarries, frankly, are great for guys by the name of Fazio or Dye because of their freakish geography…no bulldozers required. But it’s not just the freakish designers. Tom Doak, Coore ‘n’ Crenshaw, and Gil Hanse all jumped in on Streamsong.

There are at least five good reasons why mines, garbage dumps, and other “brownfields” (industrial sites considered considered too toxic to live upon) should continue as the most prominent trend in golf course development.

I. The Possibilities Are Endless

Mines aren’t exactly flexible pieces of property to work with. You kinda get what you get, and that absolutely works for locales such as the aforementioned Black Diamond.

Other man-made ecological disasters make for more flexible opportunities, however. The former phosphate mine at Streamsong is a nice option for the Doaks and Hanses of the world. It’s already been buried in sand, which is their preferred base layer. The holes are “already there,” in the natural sense. But it gets more fun when you look at something like Ferry Point in The Bronx. Prior to Jack Nicklaus, it looked nothing like it does now. Ferry Point is potentially the most artificial linksland in existence. Building something like this in New York City, without further context, is absurd. But if the city wants to bury an old landfill, who really cares how much soil you pile and shape on top? The constructed dunes are no more unnatural than if it were pancake-flat.

It’s not as romantic as Bandon’s natural curves, but there’s potential sexiness in the artificial (don’t tell Black Metal Bride about that last sentence). If Mike Keiser decided to buy some industrial wasteland, he could probably get some Kings-Collins misfits to craft something unbelievable.

II. Better Than Virgin Land

This header was not written to get my wife’s Baphomet, unlike the last paragraph’s opener.

No question golf has moved forward in serving as an environmental steward. Audubon-affirmation is taken seriously, and striven for. Most people who appreciate golf course architecture appreciate environmental considerations…until environmental considerations mean not building a golf course. Consider Keiser’s potential Scottish project, currently on hold while the government considers whether it will do undue damage to the surrounding ecosystem. Many ardent golfers simply cannot handle the reasonable nature of that argument.

It’s great when the aforementioned Kings-Collins finds a beautiful piece of property in Nebraska. But if we’re looking at flexible land we can recycle, without complaints from housing advocates, why in the hell wouldn’t we? Sometimes it’s reasonable to leave Mother Nature alone.

III. It Costs More

This is a terrible header, which does nothing to express the benefits of developing brownfields, but we moved it up because it’s the immediate counterargument to the “why wouldn’t we” question. The main reason why we look for virgin land, versus reforming used land, is because it’s considerably cheaper. This fact cannot be denied.

Brownfields require the obvious costs that come with building a golf course. Things then get considerably more expensive when you take into account the systems required to make something like a landfill safe to play on, such as the release of methane from the soil base, and all licensure required to operate a golf club on such property. That’s why Ferry Point became a decade-plus project, and how Donald Trump came to have his name on it. It’s why Liberty National had a staggering $250 million budget, more than 90% of which went to the Superfund clean-up.

But here’s the positive: If a project has this high of a budget to begin with, it’s less daunting to throw bigger budgets at bigger names to turn the property into a medalist. Considering the amount of charity work guys like Doak and Hanse (and in the past, Dye) are volunteering for, a quality public works project might not be unrealistic.

IV. Public Golf Becomes More Likely

We’ve still got beef with Liberty National, despite it living up to our premise thus far. It’s not so much that the course cost $250 million, or that it’s private, but rather that it’s both. That $250 million did not come out of the pocket of Paul Fireman, but rather out of the taxbase as a whole. Superfunds are a government program, and that’s how those things work. If a Superfund is used to restore the land on which clubs like Liberty and Bayonne rest, the public should have some right to it. We’re not saying brownfields are an ideal place to build a municipal golf course, because the costs of operation will probably be too high, and the tee times will probably end up on the high side as well. Inclusion of FirstTee and other groups will help the social factor, however.

The use of public funds also justifies leaving the courses under public control, via the cities that host them. One example is McCullough’s near Atlantic City, where players happily play around methane lamps for a quality round.

V. If You Liked It Then You Should Have Put a Green on It

We saved the best, and most obvious, for last. Golf-courses-versus-housing-developments is a major battleground elsewhere in the country, and will remain so. That’s not the case with brownfields and landfills, and is unlikely to be the case at former mining locations. Golf should take advantage.

And, realizing of course that humanity needs someplace to live, there are two significant reasons why golf is better than housing in these dark environmental times. For one, obviously grass and other vegetation perform photosynthesis much better than buildings, and certainly much better than industrial sludge.

Secondly, and less-discussed among Midwesterners such as ourselves, is the danger to flood plains that human construction causes, from housing to retail. Simply put, if there is a parking lot or any other concrete over the soil, it won’t take in water. This has led to flooding caused by hurricanes and other storms to encroach more aggressively inland across the past few decades. No one wants their golf course to serve as a flood buffer…but it does so much more effectively than a condominium complex.