BPBM was fortunate to check out Bulle Rock—a Pete Dye layout that’s typically ranked the best public course in Maryland—and we found the course’s “signature” hole a little suspect. Here’s why, and a more subtle hole from Bulle Rock’s many subtle joys, which better displays Dye’s knack for fun golf.

There was a point when young BPBM, age 24 or so, did not golf. The extent of his golfing was buying Tiger Woods PGA Tour ‘13 and playing the heck out of it. And through this, I became intensely aware of the diversity that existed among golf courses, and the first seeds of golf architectural appreciation were sown. No one in my family was a serious golfer, so I had never really considered it. Maybe guys who have played for years have a firm grasp on the wonder of angles when playing the Old Course. But for a guy with no real background in golf, I was more interested in “look how deep that frigging bunker is.” I was a noob.

It is easy for someone who appreciates the aesthetics of exotic golf courses, especially through video games, to appreciate Pete Dye as well. That Tiger Woods title featured TPC Sawgrass, Whistling Straits, Kiawah’s Ocean Course, the Blackwolf Run River Course, and Crooked Stick. A mouth-watering array of visual delights.

Granted, as I learned the subtleties of design, I was happy to learn Pete Dye really was that great. But at the onset, all I cared about were the eye-catching elements. The island green. The extra 700 bunkers at Straits that you have no chance of hitting. The live oak in the middle of a fairway.

If this is what you think of when you think “Dye,” that’s OK. Because that’s exactly what courses like Sawgrass and Whistling Straits are selling you (guess what image greets you when you visit the Sawgrass homepage?)

This can be a problem, however. The island green at Sawgrass has earned its notoriety as a great hole for professionals and, even if it’s a terrible hole for the tourist golfer, we end up loving the opportunity to hold that gun to our heads. That’s reasonable. But sometimes the standout, signature hazard at a course does a disservice to our appreciation of Dye because, well, it’s just not a great hole.

I learned this firsthand at Bulle Rock in Havre De Grace, MD. It’s the top-ranked public in the Old Line State, and that title is deserved. But there is one hole that is photographed more than any other…but maybe we should be focusing our attention elsewhere to understand Dye’s genius.

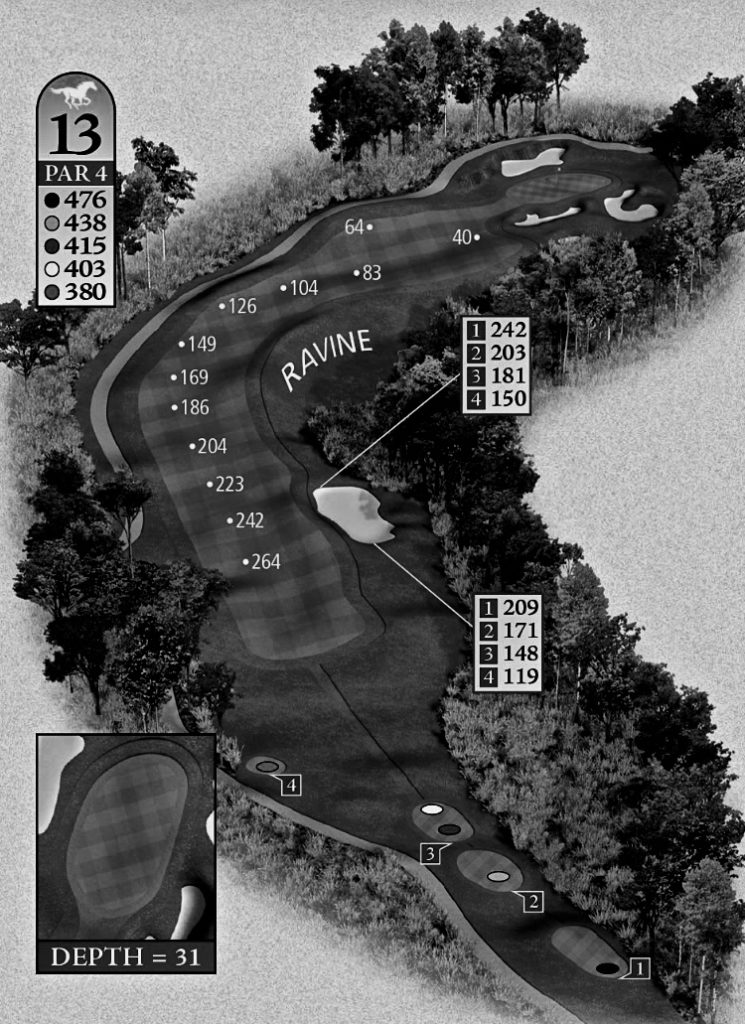

No. 13

It’s not clear whether Bulle Rock considers itself to have an actual “signature” hole. Some might consider the cape-type closer—a Par 4 traced by a pond, with a green seemingly built atop a pile of boulders—as the course headliner. Regardless, there is one hole I see photographed more prominently than any other—at the Dye Designs site, at Tim Liddy’s site, in the coffee table book ironically placed on my bedside table: No. 13, and its noteworthy ravine.

One course’s “ravine” is another’s “swale.” The ravine at Bulle Rock is alegit. Just like watching The Masters on TV, photographs don’t do justice to the altitude change at No. 13. It is deep, and makes one appreciate the nerve of whoever mows along the slope to create the attractive pattern seen in the photos linked above. Note how boldly “RAVINE” is spelled out on the yardage guide. There is a colony of overweight individuals who walked down to play a shank, and were unable to escape. We may have have made the last thing up.

It is a death trap for your scorecard, and it absolutely belongs within a Dye course. The current setup, however, doesn’t do enough to engage the best golfers, and it offers no kindness to mid-level handicappers.

Playing from the Blue tees (6,400), No. 13 clocks in at 415 yards. Not inhumane by itself, but it’s a nearly 90-degree dogleg right. The best bet for a mid-handicapper is to drive it straight-ahead 265 yards and look at a 150-yard approach. It’d be nice if the dogleg tempted better golfers to either A) add yards with a draw or B) get a better angle by challenging the corner.

It does neither.

First, the closer you are to the corner, the less friendly your approach to a green that clearly benefits a left-to-right trajectory. Secondly, few sane first-timers will try the power draw because the tee shot is uphill; you can’t even see the ravine, so why would you be tempted to mess with it?

The green complex itself is excellent, and would be so on-point if it were added to a hole such as No. 4. Bunkers below the green on the right, and above on the left (complete with Pete’s classic railroad ties). It’s the kind of thing that encourages players to play for an intelligent approach from the tee. No. 13, however, has no possible way of setting up an ideal approach. The fairway pulls up too short. Unless you’re playing from the left rough, there is no way to set yourself up for safe entrance to the green. It’s a contradiction to the rest of the course’s design strategy; where a risk from the tee sets up a scoring opportunity, and playing it safe from the tee makes scoring difficult. That’s a Dye paradigm I love.

No. 13 looks cool. We wish it played the same way. Now here’s a hole at Bulle Rock that deserves some adulation, even if it doesn’t come off as sexy in photos.

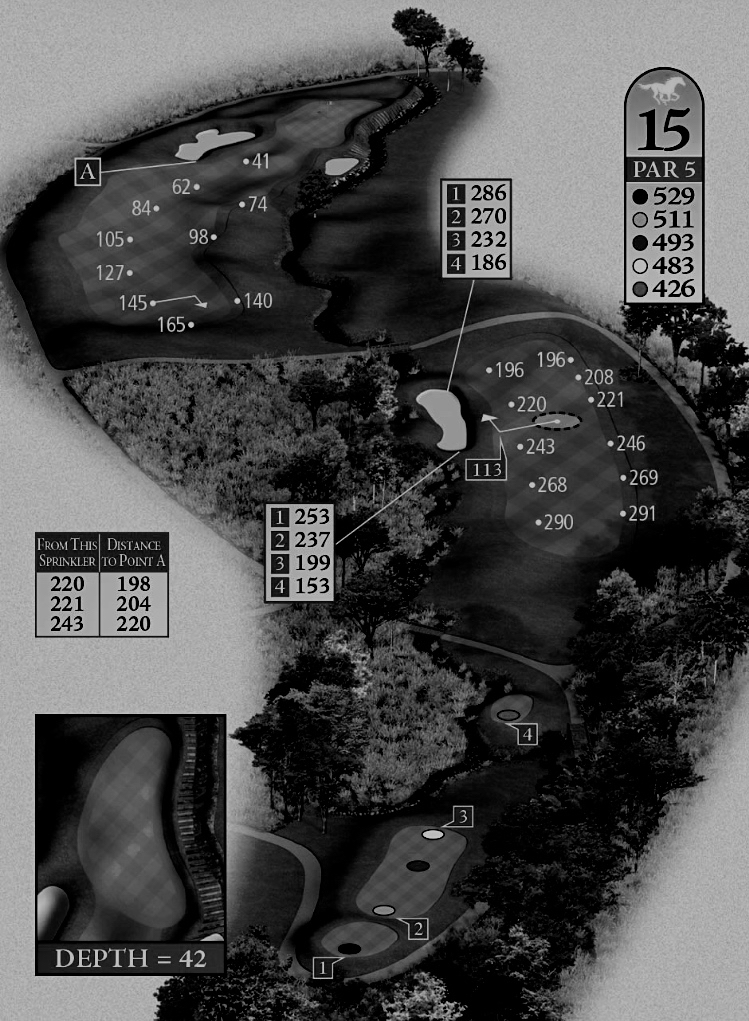

NO. 15

The variety among the Par 5s at Bulle Rock is exactly what you’d expect from a Dye design. Three are reachable, and two more so than the others. No. 8 is your best scoring opportunity, while the elevated green at the photo-friendly No. 2 may be enough to scare the big hitters into a lay-up. The multitude of subtle discouraging factors make No. 15 seem every bit as gettable as the shorter No. 8, even if it plays almost as dangerously as No. 2.

But it takes more than “gettability” to make a great Par 5. The conversation shouldn’t end at “can I reach or not?” Every shot should have at least two options. Tee shots are easy enough for designers to figure out (unless you’re playing at the blandest of “freeway”-school designs): Do I play so my approach is closer to, or farther from the green? Obvious design logic is that you make it so conservative players (read: me) can breathe relatively easy off the tee. That’s why the right side of the fairway is so bare…there’s no cost to you if you’re not planning on an eagle putt (it was a wet day…maybe next time). If we were eagle hunting, we would play down the left side, and be forced to contend with the large bunker that stretches 33 yards along its edge.

Okay, so you’ve landed in the fairway. Now you’ve got your second decision. If your drive was good, you’ll be looking at 195-210 to the center of the green. You’ll be challenged, of course. You’ll be playing left-to-right, to a green that’s above your current lie. Make the ball fade too fast, and you’ll probably end up in the creek that splits the hole’s two fairways. Make it wait too long to fade, and there’s a singular tree that even The Fried Egg can appreciate for its strategic role. Play it too short and you’ll find a deep bunker at the green’s front-right (don’t worry Dye fans…there are railway ties on this hole too).

So what if you opt to lay up? Dye forces you to make a decision here as well, and that’s what qualifies it as an excellent hole. Less thorough Par 5s typically allow the player to lay up as close as they can without facing an indictment. Not so here. There is a generous, fat piece of fairway for you to lay up to, which will leave you room for anything from a short iron to half wedge. Want to get closer than 60 yards? Suddenly the fairway pinches up, and you’ve got another 30-yard bunker waiting for you to roll off it.

No matter what set of options you take, the final piece in the puzzle is the green, which—at 42 yards—is one of the longest on the course. Pin placement reconfigures the thought process on a daily basis.

And we can’t wait to see how it treats us the next time we come to town. That’s the true sign of a designer who knows what he’s doing. Of course, we certainly don’t mind if there are poster-worthy design elements tossed into the mix.

Good stuff. Interesting point on the Bulle Rock’s Ravine hole. Would it be a better hole (i.e. a more tempting risk-reward) if you moved all the tees up say, 30 or 40 yards?

That would definitely be an improvement, in that shaping shots would be easier for players comfortable with the course. But even if you move the tees up, you’re still looking at a blind shot, and I’m still not exactly hot on blind shots where potentially devastating hazards are in play (some people are, however). It’s not an easy part of the property to work with, as the entirety of the hole is tucked into a downward amphitheater toward the creek at the bottom of the ravine. My first inclination is to move the teebox both forward and left—and then move some earth to create a larger landing area where the current fairway bunker lies. This would make laying up for a longer approach the “smart” option. But, you could also see the ravine from the teebox, and choose to play into the tighter landing area to create a shorter approach (which also plays to a friendlier angle). But, to be fair, not standing on the property, it’s tough to say whether my proposed teebox is realistic. For now, as always, I’m just that asshole pointing from the internet.