Ranking the courses in any region—especially one as golf -rich as Ohio—is very much grasping at pins. Selecting a feature—a green, a bunker, a creek, even a dip in the fairway—that best defines those courses is an even more subjective exercise…which is of course why we’re doing it. “Ohio in 50 Features” aims to highlight the Top 50 courses in the Buckeye State and focus on one key element at the course that gives a greater representation of the the club’s style, its architect, its history, and—hopefully—some fodder for you to check it out when you’re in the region. Our first entry is a worthwhile municipal offering in the Greater Cleveland / Akron areas, Sleepy Hollow Golf Course.

Ohio is not a state where views come in plenty. Looking past the first fairway and into the horizon at Sleepy Hollow Golf Course is among the best you’ll find. At the perfect Fall moment, a vista of autumn leaves stretches for upwards of 20 miles. It’s not quite a page in Ansel Adams’s greatest hits, but this view comes to you courtesy of Cuyahoga Valley National Park, a long network of acquired property and existing metro parks stretching along the title river for more than 20 miles. The course itself is a rarity in that it sits within the National Park, but Cuyahoga features more private businesses within its borders than any other U.S. national because it gained National status at the turn of the millennium, long after suburbia grew in. The first hole, a reachable Par 5, travels downhill, as does everything that follows it, eventually reaching the Cuyahoga River. At the farthest corner of the property, adjoining the Brecksville Reservation, is the No. 14 tee box.

It is not the most popular hole at the course.

Clocked at 497 from the back tees, No 14 sounds reachable on paper—but the combination of an uphill tee shot, no real chance of clearing the creek at the end of the lay-up area (325 yards of carry), and forest filing the inside of a sharp dogleg right mean this green is only attainable for the biggest hitters, who can clear the tree line with a shot traveling more than 220. Worse, the hole can become a nightmare for players who don’t get up the hill, and are forced to hit again. Three shots to get to the corner of a tree-filled dogleg…almost the prototype for the parkland-style nightmare.

Any of these players—high or low handicap—may find themselves surprised when they go looking for a slight slice that only barely edged into the trees. Stick your head into the brush, and then back away quickly.

There isn’t anything there at all.

⇟

The Cuyahoga River Valley, like almost every other basin in Ohio, was forged by glaciers. That ice did not move in the most streamlined of manners, resulting in the varicose veins you see on most watershed maps. The result at Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a range of creeks and waterfalls such as Brandywine, the tallest in the state and—a few miles away on the other side of the river—Blue Hen and Buttermilk. At Sleepy Hollow, the evidence remains in a series of ravines that designer Stanley Thompson placed Par 3 greens along (the Canadian icon was noted for choosing the sites for his short greens first, to best take advantage of the property’s natural features).

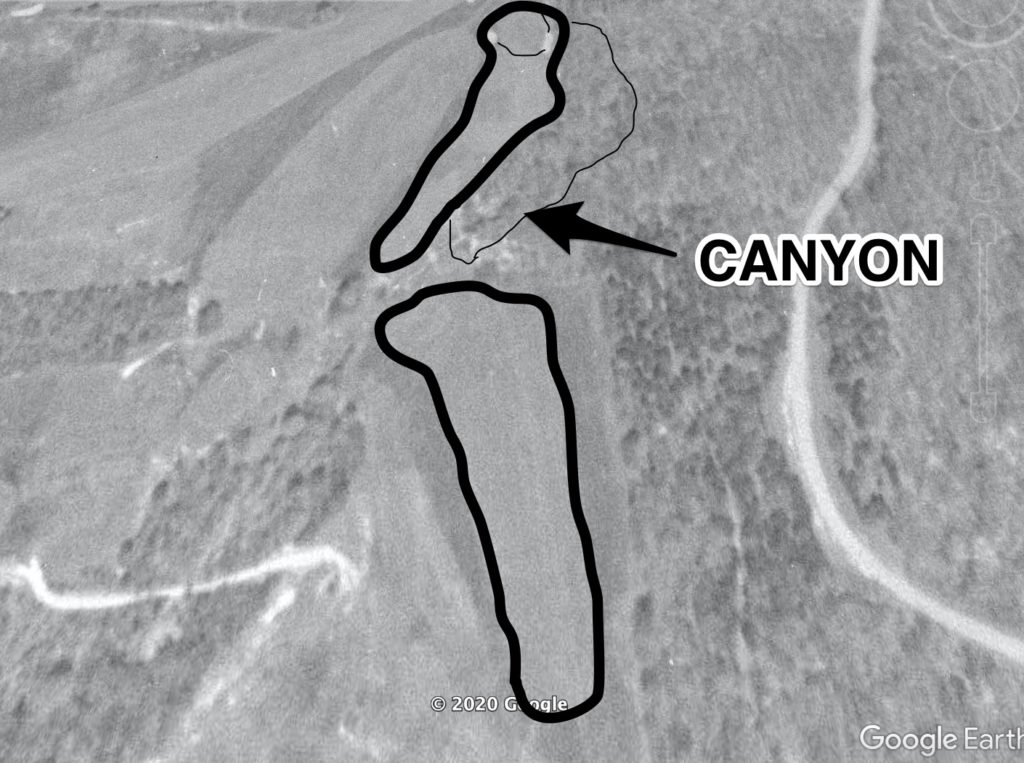

One lesser-known piece of glacier memorabilia: The Canyon.

Even among the numerous ravines at Sleepy Hollow, the drop-off along the right side of the No. 14 fairway is severe and—unlike the present day— totally visible when the club opened during 1921. Players of that era would have driven to the crest of the hill and seen a majestic view totally unlike today’s second shot. The canyon ran along the final 150 yards toward the green, daring players to bite off as much as they could chew—not unlike the second tee shot at The Pete Dye Club in West Virginia. For as intimidating as Dye’s many Cape-style tee shots around water are, a simple “splash” has nothing on watching a doomed ball careen into the depths of a 75-foot deep canyon, trees at the bottom obscuring its final destination.

Ohio is not known for spectacular geography and, accordingly, “The Canyon Hole” became notorious in the region. Writers commended it as one of the most exciting holes in the golf-rich Cleveland area, both for its visual and strategic appeal. Distance itself never made it an issue to get home in two, even for the era’s technology. As The Cleveland Plain Dealer noted during its preview of the 1938 U.S. Open qualifier, however, the canyon’s presence ate at nerves and quickly exaggerated scoring.

“The most terrifying place on the course is the ‘canyon’ on No. 14, a Par 5 hole that will be about 500 yards or so for the Open qualifier. The canyon or gorge is some 75 feet deep and straight down. It lies to the right of the fairway and can be avoided easily by a player only interested in his par 5. The trick is to loft a second shot over the canyon and reach the green in two blows for a birdie. Most of the pros can get home with a drive and a spoon, or perhaps with a two or a 3 iron with the second shot, but the penalty for a miss is heavy. A possible birdie 4 can turn into a 7 in a twinkling. A ball dropped into the abyss is there to stay. There is no chance to make a sensational recovery.”

Stanley Thompson’s flair for dramatic holes stands without question, considering the heritage of his course series within Canadian national parks. It’s appropriate coincidence the land Sleepy Hollow sits upon would one day become integrated into an American national park, to showcase yet another prime example of Thompson using gold-feature landforms to create gold-standard golf holes.

That is assuming, of course, that Stanley Thompson designed “The Canyon Hole.”

⇟

Sleepy Hollow advertises itself as a Stanley Thompson, and most reference sites will tell you the same thing. They are not wrong, but that glass is only half-full.

Of any Golden Age architect, Donald Ross is falsely cited more than any other, and the management at these clubs will hiss and spit if you suggest false lineage. Fortunately, John Fiander—the PGA Professional at Sleepy Hollow—is much more reasonable. He has dedicated some time to pondering the verity of the Thompson claims at Sleepy Hollow, and has always had questions of his own. For one, the bunkers have always struck Fiander as strange. They’re all quite rounded, a far cry from the more ill-defined, high-flashed sand hazards of Thompson’s portfolio. At the same time, Fiander also possesses a copy of the original routing, attributed to “Stanley Thompson & Company” (no bunkers are seen on the map, which Fiander suggests may imply Thompson left the task to another individual).

More clips from the Plain Dealer begin to make sense of both what Fiander’s documents prove, and what his gut suggests. From 1922:

“Harry Bandy and Howard Hollinger, who have outlined the first nine holes, which they expect to be ready for play by mid-summer, have wisely utilized every facility accorded by nature. Their plan for the course follows the high ground in a manner that brings the hollows, rough, water and woods into the best possible play.”

If Harry Bandy and Howard Hollinger are not familiar names, it is perhaps because they did not design anything afterwards (Hollinger may have designed the Silverleaf Country Club, but records are unlikely because of its closure; it is not related to the current Ohio club of the same name). Considering the names who had designed Cleveland clubs during the early 20th Century—Ross, Alison, Flynn, Tillinghast and yes, Thompson—it was perhaps surprising that a fledgeling club opted to tap local talent to scout and begin building a new course (Alison, in fact, was building Kirtland at the time when property for Sleepy Hollow was acquired).

Still, if shopping local, there were few more qualified than this pair. Bandy was the secretary of the recently-formed Cleveland District Golf Association, but Hollinger was the belle of the city golf scene. He had won the Ohio State Amateur during 1917, a strangely rare occurrence for the city’s golfers in that era despite the relative wealth of clubs available. Accordingly, everyone who claimed to love golf wanted to be involved with him. During the brief period where newspapers were covering the development of Sleepy Hollow, Hollinger is separately cited as a member of Portage Country Club, Chagrin Valley Country Club, Dover Bay Country Club and Silver Leaf Country Club (again, not the same club as currently exists).

So what about the Thompson claims? No fear of fakery on Sleepy Hollow’s part: A 1924 article confirms that Thompson arrived to round out the full 18. One question not clarified by the writer: Which architectural team handled which nine (and, more importantly, “The Canyon Hole”)? The same article presents a full scorecard of holes and yardages; theoretically, either hole No. 5 or 14 would be a Par 5 (depending on whether Bandy and Hollinger’s work was moved to the back nine, or remained as the opening nine). Neither of these holes is a Par 5 as of 1924, but both Nos. 4 and 13 were.

Fortunately the answer is as simple as asking Fiander, and that answer rings with some truth regarding Thompson’s tendencies. As has been noted already, Thompson’s first step when designing was to locate sites for his Par 3s. Those who have played Sleepy Hollow know that the front nine features three pieces of short eye-candy: No. 2, which plays more than 230 yards along a wetland area, No. 6, which plays across one of the property’s ravines and No. 8, which can be forgiven for behaving much like No. 6. The Thompson routing indicates that there had previously been two short holes on the original nine, and it seems he simply eradicated one of them. Admittedly, it seemed to sit in a valley with no drama to frame it—something that Thompson surely considered to be an amateur-hour move whole he toured the property. The rookie nature of the Bandy/Hollinger duo made itself evident in the article previewing the Open qualifying.

“We laid it out pretty well I thought,” Bandy told the paper. “But we sort of forgot to get any grass on the greens. That was somewhat bad and had to be rectified.”

Perhaps Bandy and Hollinger were not the finest architectural minds who touched the ground at Sleepy Hollow. But even with Thompson’s Par 3 improvements, it cannot be denied their Canyon Hole continued to be the star of the club’s roster.

⇟

As alluded to, that canyon no longer plays into the hole’s strategy. Trees have grown up and around the rim of the gorge to the extent few even realize such a landform exists. So what happened to it?

The commonplace reaction from architectural hobbyists when looking at the club’s history is to blame Cleveland Metro Parks; public play began at the course in 1961.

But, like the course’s design heritage, the story is much trickier than leaning on the template “cheapskate muni” argument.

Sleepy Hollow did not fold to public access because of private financial troubles. Quite the opposite. Rather, the founding members made an assumption that was hardly foolproof, and when the legal ramifications finally caught up, they had literally no ground to stand on. Sleepy Hollow is well-known as part of the Cleveland Metro Parks system now, but the truth is that it always had been. The land was always part of the Brecksville Reservation, and the city rented it to Sleepy Hollow for its club. The plan worked well financially, but during 1956 a plaintiff—specifically the tax-savvy couple John B. and Margaret M. Kelly—had the gall to question the legality of the city renting public land for private use, drawing into question the status of both Sleepy Hollow and Manakiki Golf Course. It is no surprise that both of those courses now exist as gems in the city’s municipal golf crown. Members at both clubs hemmed and hawed, but the city of Cleveland decided during 1958 to not renew either club’s lease past 1960. The members, not as committed to the cause as Ammon Bundy, left.

Historic aerials show, however, that when the city changed Sleepy Hollow’s status, the existing tree line was already in place, almost identical to what you can see in the photo’s below. Why hadn’t the private club maintained its signature hole if finances remained strong?

The truth is there was literally nothing they could do about it.

Maps of the course’s original parcel indicate that the permitted development lines end at the right of No. 14, hugging the inside of the dogleg. The Canyon has never been part of the Sleepy Hollow property…merely an impressive piece of landscape that Bandy and Hollinger realized could still function well as part of a golf course. Like with the club’s founders, the pair made the shortsighted assumption that everything—from legal status to geography—would remain just the way it was circa 1922.

One potential positive, of course, is Sleepy Hollow operates as an arm of the Brecksville Reservation. The park could theoretically decide to remove the trees growing along the rim and at the tip of the canyon, thereby restoring it to glory. Fiander acknowledges the unlikelihood of this happening. however.

“That’s out of bounds and not really part of what we’ll call Sleepy Hollow Golf Course,” he notes. “But it’s with the rest of the Brecksville Reservation so it’s not impossible, I guess…it would probably be difficult, I think, for the park to justify taking down those trees.”

Which is not to say he personally wouldn’t be interested.

“I would agree it would be a visually stunning thing to hit the ball over that canyon,” he says. “If all those trees were gone, I think the visual would be something really special to see, and at that point maybe it would be a Par 4. Just a long Par 4, with everybody being able to fire across that canyon. It ends up being more of a visual impact than actual, what we’ll call a ‘hazard.’”

The fairway bunker currently sitting about 45 yards out from the green is not an original—it was added during a renovation by Brian Huntley during the late ‘90s to catch a few blind approaches from those daring to hit over the tree line—but it could be incorporated into a modern design to improve Fiander’s Par 4.5 concept. Players hitting their second would need to consider both how near to the canyon to leave their shot (the better line to the green comes from the right), as well as how far to hit the shot to avoid the bunker. Although Thompson may not have created “The Canyon Hole,” Huntley’s bunker could be expanded and given some Thompson spirit for continued aesthetic measure. The final result would be an adaptation, somewhat, of Seth Raynor’s Prize Dogleg, with the big decision made instead upon approach, rather than at the tee.

Even as a five, it might be fun, even if scoring prevailed, for even a hole prone to red numbers can still be a remarkable one. Many golf architects familiar with matchplay tactics would agree, but we’ll let legendary Cleveland sports writer John Dietrich sum it up:

“Sleepy Hollow’s fourteenth is accorded somewhat exaggerated importance because it occurs at the ‘crisis’ spot of the course. Were it No. 2, No. 4 or at a point early on in the layout, it could be approached with much more confidence and with much less travail,” he wrote in 1930, while discussing the frequency of birdies. “In fact, it is done quite often but never by anyone who has tried and missed the first time around. Failure on the initial attempt begets an inferiority complex to which the wise golfer will forever defer.”

Oh to have an opportunity for an initial attempt, regardless of the outcome.

Sleepy Hollow features many other holes worthy of a look, and some wickedly old-fashioned putting slopes on a few greens. Although Thompson may not have styled the original course’s greatest hole, his front nine is now the more desirable one, with the aforementioned Par 3s as well as the more beastly No. 3, a long Par 4 playing over hollows. Greens fees are quite moderate, and weekday play improves the speed.

Ohio resident? Think your club has a chance at the Top 50 in the state, or want to weigh in on what the best feature at your club is? Reach out and give us your pitch.

I always hated this hole. Now I know why. There’s no angle around the bend. Thank you for unearthing this.